The perineum in mammals is the space between the anus and the genitals. The human perineum is between the anus and scrotum in the male or between the anus and vulva in the female. The perineum is the region of the body between the pubic symphysis and the coccyx, including the perineal body and surrounding structures. The perineal raphe is visible and pronounced to varying degrees. The perineum is an erogenous zone. This area is also known as the taint or gooch in American slang.

The pudendal nerve is the main nerve of the perineum. It is a mixed nerve and also conveys sympathetic autonomic fibers. It carries sensation from the external genitalia of both sexes and the skin around the anus and perineum, as well as the motor supply to various pelvic muscles, including the male or female external urethral sphincter and the external anal sphincter.

Fecal incontinence (FI), or in some forms, encopresis, is a lack of control over defecation, leading to involuntary loss of bowel contents, both liquid stool elements and mucus, or solid feces. When this loss includes flatus (gas), it is referred to as anal incontinence. FI is a sign or a symptom, not a diagnosis. Incontinence can result from different causes and might occur with either constipation or diarrhea. Continence is maintained by several interrelated factors, including the anal sampling mechanism, and incontinence usually results from a deficiency of multiple mechanisms. The most common causes are thought to be immediate or delayed damage from childbirth, complications from prior anorectal surgery, altered bowel habits. An estimated 2.2% of community-dwelling adults are affected. However, reported prevalence figures vary. A prevalence of 8.39% among non-institutionalized U.S adults between 2005 and 2010 has been reported, and among institutionalized elders figures come close to 50%.

The levator ani is a broad, thin muscle group, situated on either side of the pelvis. It is formed from three muscle components: the pubococcygeus, the iliococcygeus, and the puborectalis.

The coccyx, commonly referred to as the tailbone, is the final segment of the vertebral column in all apes, and analogous structures in certain other mammals such as horses. In tailless primates since Nacholapithecus, the coccyx is the remnant of a vestigial tail. In animals with bony tails, it is known as tailhead or dock, in bird anatomy as tailfan. It comprises three to five separate or fused coccygeal vertebrae below the sacrum, attached to the sacrum by a fibrocartilaginous joint, the sacrococcygeal symphysis, which permits limited movement between the sacrum and the coccyx.

A rectal prolapse occurs when walls of the rectum have prolapsed to such a degree that they protrude out of the anus and are visible outside the body. However, most researchers agree that there are 3 to 5 different types of rectal prolapse, depending on whether the prolapsed section is visible externally, and whether the full or only partial thickness of the rectal wall is involved.

The pelvic floor or pelvic diaphragm is an anatomical location in the human body, which has an important role in urinary and anal continence, sexual function and support of the pelvic organs. The pelvic floor includes muscles, both skeletal and smooth, ligaments and fascia. and separates between the pelvic cavity from above, and the perineum from below. It is formed by the levator ani muscle and coccygeus muscle, and associated connective tissue.

The anal canal is the part that connects the rectum to the anus, located below the level of the pelvic diaphragm. It is located within the anal triangle of the perineum, between the right and left ischioanal fossa. As the final functional segment of the bowel, it functions to regulate release of excrement by two muscular sphincter complexes. The anus is the aperture at the terminal portion of the anal canal.

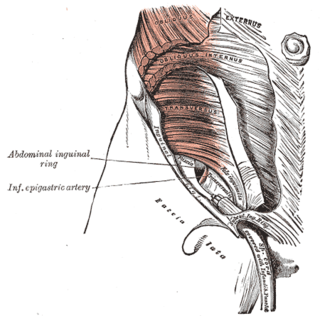

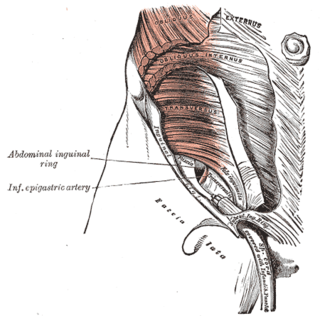

The transversalis fascia is the fascial lining of the anterolateral abdominal wall situated between the inner surface of the transverse abdominal muscle, and the preperitoneal fascia. It is directly continuous with the iliac fascia, the internal spermatic fascia, and pelvic fascia.

The muscular layer is a region of muscle in many organs in the vertebrate body, adjacent to the submucosa. It is responsible for gut movement such as peristalsis. The Latin, tunica muscularis, may also be used.

The pelvic fasciae are the fascia of the pelvis and can be divided into:

The superior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm is continuous with the obturator fascia and stretches across the pubic arch.

Defecography is a type of medical radiological imaging in which the mechanics of a patient's defecation are visualized in real time using a fluoroscope. The anatomy and function of the anorectum and pelvic floor can be dynamically studied at various stages during defecation.

The rectum is the final straight portion of the large intestine in humans and some other mammals, and the gut in others. The adult human rectum is about 12 centimetres (4.7 in) long, and begins at the rectosigmoid junction at the level of the third sacral vertebra or the sacral promontory depending upon what definition is used. Its diameter is similar to that of the sigmoid colon at its commencement, but it is dilated near its termination, forming the rectal ampulla. It terminates at the level of the anorectal ring or the dentate line, again depending upon which definition is used. In humans, the rectum is followed by the anal canal which is about 4 centimetres (1.6 in) long, before the gastrointestinal tract terminates at the anal verge. The word rectum comes from the Latin rectumintestinum, meaning straight intestine.

In humans, the anus is the external opening of the rectum located inside the intergluteal cleft. Two sphincters control the exit of feces from the body during an act of defecation, which is the primary function of the anus. These are the internal anal sphincter and the external anal sphincter, which are circular muscles that normally maintain constriction of the orifice and which relaxes as required by normal physiological functioning. The inner sphincter is involuntary and the outer is voluntary. Above the anus is the perineum, which is also located beneath the vulva or scrotum.

The pelvis is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs, together with its embedded skeleton.

Anismus or dyssynergic defecation is the failure of normal relaxation of pelvic floor muscles during attempted defecation. It can occur in both children and adults, and in both men and women. It can be caused by physical defects or it can occur for other reasons or unknown reasons. Anismus that has a behavioral cause could be viewed as having similarities with parcopresis, or psychogenic fecal retention.

Obstructed defecation syndrome is a major cause of functional constipation, of which it is considered a subtype. It is characterized by difficult and/or incomplete emptying of the rectum with or without an actual reduction in the number of bowel movements per week. Normal definitions of functional constipation include infrequent bowel movements and hard stools. In contrast, ODS may occur with frequent bowel movements and even with soft stools, and the colonic transit time may be normal, but delayed in the rectum and sigmoid colon.

In fecal incontinence (FI), surgery may be carried out if conservative measures alone are not sufficient to control symptoms. There are many surgical options described for FI, and they can be considered in 4 general groups.

The vaginal support structures are those muscles, bones, ligaments, tendons, membranes and fascia, of the pelvic floor that maintain the position of the vagina within the pelvic cavity and allow the normal functioning of the vagina and other reproductive structures in the female. Defects or injuries to these support structures in the pelvic floor leads to pelvic organ prolapse. Anatomical and congenital variations of vaginal support structures can predispose a woman to further dysfunction and prolapse later in life. The urethra is part of the anterior wall of the vagina and damage to the support structures there can lead to incontinence and urinary retention.