This article is about a term in Jain phenomenology. For Buddhist use, see

Skandha. For the bodhisattva by a similar name, see

Skanda (Buddhism).

Skandha (Sanskrit) means "heaps, aggregates, collections, groupings". In the religion of Jainism, Skandha is a combination of Paramanus (elementary particles). In contrast to Buddhism that allows aggregates of non-matters, Jainism allows only aggregation between matter (only first type out of the five types of aggregates allowed in Buddhism). Jainism doesn't include the last four types of aggregates of Buddhism because those phenomena are explained in Jainism by the groupings between matter (karma particles, second last from the list below) and Atman (unified individual whose existence is denied in Buddhism). A grouping between matter and Atman is not considered a Skandha but is considered a Bandha (bondage).

Each Paramanu has "intensity points" of aridness or cohesiveness that, because of transformation, can increase or decrease between one and infinity. These Paramanus can combine with each other to create Skandhas or Aggregates when there is a difference of two "intensity points", whether it is arid or cohesive or whether having even or odd "intensity points" except the minimum (one) "intensity point". For example, a paramanu with two points of cohesiveness can combine with a paramanu of four points of cohesiveness or aridness; and that of three points with that of five points and so on. [1] This definition is given in Pravachanasara.

Skandhas and Paramanus are two types of Pudgalas (Matter).

Skandha are of six types: Gross-gross, gross, gross-fine, fine-gross, fine, and fine-fine. [2] This classification is given in Niyamsara.

- Gross-gross: Solids, such as stone and wood, that when broken cannot be united again by themselves.

- Gross: Milk, water, etc. separated but can unite without any help.

- Gross-fine: The sunlight, shade, moon light, darkness etc. One is not able to split them. One is not able to grab them with his hands.

- Fine-gross: The objects of the four senses of touch, taste, smell, and hearing are even though are known by skin, tongue, nose and ears but still cannot be perceived by eyes and that is why they are fine-gross in nature.

- Fine: The matter particles of the karma are fine in nature and cannot be perceived by any of the physical senses.

- Fine-fine: Finer than the karma particles are extremely fine in nature. They are finer than karma particles.

Vaisheshika or Vaiśeṣika is one of the six schools of [Indian philosophy]] from ancient India. In its early stages, the Vaiśeṣika was an independent philosophy with its own metaphysics, epistemology, logic, ethics, and soteriology. Over time, the Vaiśeṣika system became similar in its philosophical procedures, ethical conclusions and soteriology to the Nyāya school of Hinduism, but retained its difference in epistemology and metaphysics.

Rebirth in Buddhism refers to its teaching that the actions of a person lead to a new existence after death, in endless cycles called saṃsāra. This cycle is considered to be dukkha, unsatisfactory and painful. The cycle stops only if liberation is achieved by insight and the extinguishing of desire. Rebirth is one of the foundational doctrines of Buddhism, along with Karma, nirvana and moksha.

The Pudgalavāda was a Buddhist philosophical view and also refers to a group of Nikaya Buddhist schools that arose from the Sthavira nikāya. The school is believed to have been founded by the elder Vātsīputra in the third century BCE. They were a widely influential school in India and became particularly popular during the reign of emperor Harshavadana. Harsha's sister Rajyasri was said to have joined the school as a nun. According to Dan Lusthaus, they were "one of the most popular mainstream Buddhist sects in India for more than a thousand years."

Ajivika is one of the nāstika or "heterodox" schools of Indian philosophy. Purportedly founded in the 5th century BCE by Makkhali Gosala, it was a śramaṇa movement and a major rival of Vedic religion, early Buddhism and Jainism. Ājīvikas were organised renunciates who formed discrete communities. The precise identity of the Ajivikas is not well known, and it is even unclear if they were a divergent sect of the Buddhists or the Jains.

Tattva is a Sanskrit word meaning 'thatness', 'principle', 'reality' or 'truth'. According to various Indian schools of philosophy, a tattva is an element or aspect of reality. In some traditions, they are conceived as an aspect of deity. Although the number of tattvas varies depending on the philosophical school, together they are thought to form the basis of all our experience. The Samkhya philosophy uses a system of 25 tattvas, while Shaivism recognises 36 tattvas. In Buddhism, the equivalent is the list of dhammas which constitute reality.

Ajiva (Sanskrit) is anything that has no soul or life, the polar opposite of "jīva" (soul). Because ajiva has no life, it does not accumulate karma and cannot die. Examples of ajiva include chairs, computers, paper, plastic, etc. According to Jain philosophy, Ajiva can be divided into two kinds, with form and without form.

In Jainism, Pudgala is one of the six Dravyas, or aspects of reality that fabricate the world we live in. The six dravyas include the jiva and the fivefold divisions of ajiva (non-living) category: dharma (motion), adharma (rest), akasha (space), pudgala (matter) and kala (time). Pudgala, like other dravyas except kala is called astikaya in the sense that it occupies space.

Karma is the basic principle within an overarching psycho-cosmology in Jainism. Human moral actions form the basis of the transmigration of the soul. The soul is constrained to a cycle of rebirth, trapped within the temporal world, until it finally achieves liberation. Liberation is achieved by following a path of purification.

Jainism does not support belief in a creator deity. According to Jain doctrine, the universe and its constituents—soul, matter, space, time, and principles of motion—have always existed. All the constituents and actions are governed by universal natural laws. It is not possible to create matter out of nothing and hence the sum total of matter in the universe remains the same. Jain text claims that the universe consists of jiva and ajiva. The soul of each living being is unique and uncreated and has existed since beginningless time.

Jain philosophy is the oldest Indian philosophy that separates body (matter) from the soul (consciousness) completely. Jain philosophy deals with reality, cosmology, epistemology and Vitalism. It attempts to explain the rationale of being and existence, the nature of the Universe and its constituents, the nature of soul's bondage with body and the means to achieve liberation.

Skandhas (Sanskrit) or khandhas (Pāḷi) means "heaps, aggregates, collections, groupings". In Buddhism, it refers to the five aggregates of clinging (Pañcupādānakkhandhā), the five material and mental factors that take part in the rise of craving and clinging. They are also explained as the five factors that constitute and explain a sentient being’s person and personality, but this is a later interpretation in response to sarvastivadin essentialism.

Jain philosophy explains that seven tattva constitute reality. These are:—

- jīva- the soul which is characterized by consciousness

- ajīva- the non-soul

- āsrava (influx)- inflow of auspicious and evil karmic matter into the soul.

- bandha (bondage)- mutual intermingling of the soul and karmas.

- samvara (stoppage)- obstruction of the inflow of karmic matter into the soul.

- nirjara - separation or falling-off of part of karmic matter from the soul.

- mokṣha (liberation)- complete annihilation of all karmic matter.

According to Jain karma theory, there are eight main types of karma (Prikriti) which are categorized into the ‘harming’ and the ‘non-harming’; each divided into four types. The harming karmas directly affect the soul powers by impeding its perception, knowledge and energy, and also brings about delusion. These harming karmas are: darśanāvaraṇa, Jnanavarniya, antarāya and mohanīya. The non-harming category is responsible for the reborn soul's physical and mental circumstances (nāma), longevity (āyuś), spiritual potential (gotra) and experience of pleasant and unpleasant sensations (vedanīya). In other therms these non-harming karmas are: nāma, āyu, gotra and vedanīya respectively. Different types of karmas thus affect the soul in different ways as per their nature. Each of these types has various sub-types. Tattvārthasūtra generally speaks of 148 sub-types of karmas in all. These are: 5 of jñānavaraṇa, 9 of darśanavaraṇa, 2 of vedanīya, 28 of mohanīya 4 of āyuṣka, 93 of nāma, 2 of gotra, and 5 of antarāya.

Jīva or Atman is a philosophical term used within Jainism to identify the soul. As per Jain cosmology, jīva or soul is the principle of sentience and is one of the tattvas or one of the fundamental substances forming part of the universe. The Jain metaphysics, states Jagmanderlal Jaini, divides the universe into two independent, everlasting, co-existing and uncreated categories called the jiva (soul) and the ajiva. This basic premise of Jainism makes it a dualistic philosophy. The jiva, according to Jainism, is an essential part of how the process of karma, rebirth and the process of liberation from rebirth works.

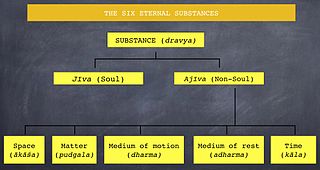

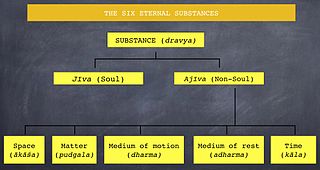

Dravya means substance or entity. According to the Jain philosophy, the universe is made up of six eternal substances: sentient beings or souls (jīva), non-sentient substance or matter (pudgala), principle of motion (dharma), the principle of rest (adharma), space (ākāśa) and time (kāla). The latter five are united as the ajiva. As per the Sanskrit etymology, dravya means substances or entity, but it may also mean real or fundamental categories.

Self-realization is an expression used in Western psychology, philosophy, and spirituality; and in Indian religions. In the Western understanding it is the "fulfillment by oneself of the possibilities of one's character or personality". In the Indian understanding, self-realization is liberating knowledge of the true Self, either as the permanent undying atman, or as the absence (sunyata) of such a permanent Self.

According to Sarira Traya, the Doctrine of the Three bodies in Hinduism, the human being is composed of three sariras or "bodies" emanating from Brahman by avidya, "ignorance" or "nescience". They are often equated with the five koshas (sheaths), which cover the atman. The Three Bodies Doctrine is an essential doctrine in Indian philosophy and religion, especially Yoga, Advaita Vedanta and Tantra.

Mithyātva means "false belief", and an important concept in Jainism and Hinduism. Disappearance (nivrtti) is the necessary presupposition of mithyatva because what is falsely perceived ceases to exist with the dawn of right knowledge. Mithyātva, states Jayatirtha, cannot be easily defined as 'indefinable', 'non-existent', 'something other than real', 'which cannot be proved, produced by avidya or as its effect', or as 'the nature of being perceived in the same locus along with its own absolute non-existence'.

Tanmatra is a noun which means – rudimentary or subtle element, merely that, mere essence, potential or only a trifle. There are five sense perceptions – hearing, touch, sight, taste and smell, and there are the five tanmatras corresponding to the five sense perceptions and five sense-organs. The tanmatras combine and re-combine in different ways to produce the gross elements – earth, water, fire, air and ether, which make up the gross universe perceived by the senses. The senses play their part by coming into contact with the objects, and carry impressions of them to the manas which receives and arranges them into a precept.

Ajñana was one of the nāstika or "heterodox" schools of ancient Indian philosophy, and the ancient school of radical Indian skepticism. It was a Śramaṇa movement and a major rival of early Buddhism, Jainism and the Ājīvika school. They have been recorded in Buddhist and Jain texts. They held that it was impossible to obtain knowledge of metaphysical nature or ascertain the truth value of philosophical propositions; and even if knowledge was possible, it was useless and disadvantageous for final salvation. They were specialized in refutation without propagating any positive doctrine of their own.