Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

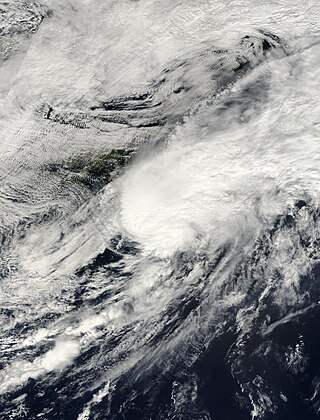

A tropical wave emerged into the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa on September 1. Due to entrainment of dry air, the wave struggled to maintain convection as it progressed westwards. [1] The National Hurricane Center (NHC) did not begin monitoring the system in its Tropical Weather Outlooks until a concentrated area of low pressure developed about 350 mi (560 km) east of the Leeward Islands on September 8. [2] The convection quickly diminished and mainly consisted of only sporadically bursts of shower and thunderstorm activity. [3] Little change in organization took place as the disturbance tracked through the Bahamas on September 11 and September 12. However, the disturbance quickly organized and developed more thunderstorm activity while approaching Florida. A tropical depression is estimated to have formed at 06:00 UTC on September 13, around the time it was making landfall in Jensen Beach, Florida. Within a few hours, a strong band of deep convection formed in the northeast quadrant of the cyclone, though westerly wind shear prevented any significant convection from developing on the western side of the storm. [1]

Radar and surface observations indicate that the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Julia around 12:00 UTC on September 13, about six hours after forming, becoming the first tropical cyclone to intensify into a tropical storm while over land. Once designated as a tropical storm, Julia reached its peak intensity of 50 mph (85 km/h) while inland, [1] At 03:00 UTC on September 14, the NHC initiated advisories on Julia – which was then centered near Jacksonville – and initially predicted that the storm would move north-northwestward and become extratropical or a remnant low pressure area over Georgia by September 16. [4] Shortly thereafter, Julia weakened slightly due to moderate to high wind shear. Periodic bursts of convection occurred near the center of the system as it moved over water and paralleled the coast of Florida and Georgia. [1] However, these bursts were short-lived due to strong wind shear, causing its elongated circulation to become far removed from the deep convection. Operationally, the NHC erroneously downgraded Julia to a tropical depression on September 15. [5] At 00:00 UTC that day, Julia attained its minimum barometric pressure of 1007 mbar (29.7 inHg ). [1]

Julia consisted of mainly a low-level swirl of clouds by late on September 16; however, minimal convection kept the storm at the minimum requirements for a tropical cyclone. [6] Early on September 17, Julia weakened to a tropical depression. [1] Despite a slight increase in convection and organization, wind shear and dry air continued to take its toll on the increasingly ill-defined storm, and Julia degenerated into a remnant low by early on September 19 after being devoid of convection for nearly 12 hours. [7] While moving north, the remnants of Julia then transitioned into a weak extratropical cyclone and made a small westward turn before dissipating inland over North Carolina on September 21. [1]

Preparations and impact

Upon initiating advisories on the storm at 03:00 UTC on September 14, the NHC issued a tropical storm warning from Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, to Altamaha Sound in Georgia. Nine hours later, the tropical storm warning was discontinued as the cyclone began moving offshore Georgia. [1] Additionally, flash flood watches were issued between Florida and North Carolina, as up to 10 in (250 mm) of rainfall was possible in some areas. Florida governor Rick Scott urged residents to prepare in case an evacuation became necessary and to dump standing water to control mosquitoes that could be carrying the Zika virus. [8] Jacksonville mayor Lenny Curry released a statement telling those in the path of the storm to stay off the roadways due to the rain and wind and potential flash flooding. [9]

In Florida, the storm produced wind gusts of 30 to 48 mph (48 to 77 km/h) along the First Coast, causing some structural damage, [10] including ripping apart the roof of a Chevron gas station in Neptune Beach and carrying it over two blocks before dropping it. [9] While Julia was still in its precursor stages as it paralleled the coast of Florida, an EF0 tornado was reported and later confirmed in the areas of Barefoot Bay, with sustained winds as high as 85 mph (137 km/h). One home had its roof partially ripped off by the tornado as it tracked through the area. [9] Flooding rain impacted the Space Coast and the First Coast, with 3.3 in (84 mm) of precipitation reported in Melbourne. [11]

The storm knocked out power to over 1,300 people in Georgia, especially in and near the Sea Islands and St. Simons. In South Carolina, rainfall from Julia caused flash flooding in a number of locations, such as the Charleston metropolitan area, where flooding resulted in the closure of several roads. Accumulations peaked at 3.67 in (93 mm) on September 14. Sporadic power outages were also reported. [9]

As the remnants of Julia interacted with a cold front near the coastline, parts of North Carolina received as much as 12 in (300 mm) of rain. One million gallons of sewage from Elizabeth City flowed into the Pasquotank River and Charles Creek. The Cashie River in Windsor, crested at 15 ft (4.6 m) on September 22, about 2 ft (0.61 m) above major flood stage. In Windsor, several businesses and approximately 60 homes suffered water damage. [12] In Bertie County alone, 72 people had to be rescued from their homes and vehicles, while 61 others were evacuated from nursing homes. [13] A shelter was opened for displaced residents. [14] Damage in the county reached about $5 million in damage, including $4 million to property and $1 million to agriculture. [15] Flooding in Bertie, Currituck, and Hertford counties resulted in school closures for at least two days. [12] On September 22, then-Governor Pat McCrory declared a state of emergency for Bertie, Camden, Chowan, Currituck, Dare, Gates, Halifax, Hertford, Northampton, Pasquotank, and Perquimans. [13] A disaster declaration was approved following Hurricane Matthew in October, which also included aid for victims of flooding during Julia. [16] The declaration allowed businesses and non-profit organizations in Bertie, Chowan, Halifax, Hertford, Martin, Northampton, and Washington counties to apply for low-interest loans via the Small Business Administration, while loans up to $200,000 became available for needy homeowners. [17]

Heavy rainfall was reported in southeastern Virginia, with 17.85 in (453 mm) of precipitation observed near Great Bridge. Numerous roads were washed out in several counties and independent cities, including Chesapeake, Franklin, Isle of Wight, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Southampton, Suffolk, and Virginia Beach. [18] In Chesapeake, flood waters overwhelmed the sewer system, causing sewage to enter the city's water system and local waterways. [12] Farther north, the remnants of the storm interacted with a frontal boundary, resulting in heavy rainfall in some portions of Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. [18] Throughout its path, damage from the storm amounted to about $6.13 million. [19]

See also

- Other storms named Julia

- List of Florida hurricanes (2000–present)

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (2000–present)

- Hurricane Ophelia (2005)

- Tropical Storm Tammy (2005)

- Tropical Storm Ana (2015)

- Hurricane Sally (2020) – strengthened to a tropical storm over Southern Florida during the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season

- Brown ocean effect – a phenomenon that causes topical cyclones to intensify over land

Related Research Articles

The 1995 Atlantic hurricane season was a very active Atlantic hurricane season, and is considered to be the start of an ongoing era of high-activity tropical cyclone formation. The season produced twenty-one tropical cyclones, nineteen named storms, as well as eleven hurricanes and five major hurricanes. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30, dates which conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones develop in the Atlantic basin. The first tropical cyclone, Hurricane Allison, developed on June 2, while the season's final storm, Hurricane Tanya, transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on November 1. The very active Atlantic hurricane activity in 1995 was caused by La Niña conditions, which also influenced an inactive Pacific hurricane season. It was tied with 1887 Atlantic hurricane season with 19 named storms. And was later in 2010, 2011, and 2012 seasons respectively.

The 2003 Atlantic hurricane season was a very active season with tropical cyclogenesis occurring before and after the official bounds of the season—the first such occurrence since the 1970 season. The season produced 21 tropical cyclones, of which 16 developed into named storms; seven of those attained hurricane status, of which three reached major hurricane status. The strongest hurricane of the season was Hurricane Isabel, which reached Category 5 status on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale northeast of the Lesser Antilles; Isabel later struck North Carolina as a Category 2 hurricane, causing $3.6 billion in damage and a total of 51 deaths across the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States.

Tropical Storm Alberto was the first tropical storm of the 2006 Atlantic hurricane season. Forming on June 10 in the northwestern Caribbean, the storm moved generally to the north, reaching a maximum intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h) before weakening and moving ashore in the Big Bend area of Florida on June 13. Alberto then moved through eastern Georgia, North Carolina, and Virginia as a tropical depression before becoming extratropical on June 14.

Tropical Storm Helene was a long-lived tropical cyclone that oscillated for ten days between a tropical wave and a 70 mph (110 km/h) tropical storm. It was the twelfth tropical cyclone and eighth tropical storm of the 2000 Atlantic hurricane season, forming on September 15 east of the Windward Islands. After degenerating into a tropical wave, the system produced flooding and mudslides in Puerto Rico. It reformed into a tropical depression on September 19 south of Cuba, and crossed the western portion of the island the next day while on the verge of dissipation. However, it intensified into a tropical storm in the Gulf of Mexico, reaching its peak intensity while approaching the northern Gulf Coast.

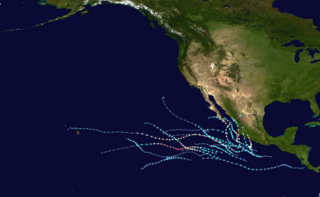

The 2011 Pacific hurricane season was a below average season in terms of named storms, although it had an above average number of hurricanes and major hurricanes. During the season, 13 tropical depressions formed along with 11 tropical storms, 10 hurricanes and 6 major hurricanes. The season officially began on May 15 in the East Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Pacific basin. The season's first cyclone, Hurricane Adrian formed on June 7, and the last, Hurricane Kenneth, dissipated on November 25.

The 2012 Pacific hurricane season was a moderately active Pacific hurricane season that saw an unusually high number of tropical cyclones pass west of the Baja California Peninsula. The season officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the central Pacific (from 140°W to the International Date Line, north of the equator; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in these regions of the Pacific Ocean. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year. This season's first system, Tropical Storm Aletta, formed on May 14, and the last, Tropical Storm Rosa, dissipated on November 3.

The 2010 Atlantic hurricane season was the first of three consecutive very active Atlantic hurricane seasons, each with 19 named storms. This above average activity included 12 hurricanes, equaling the number that formed in 1969. Only the 2020 and 2005 seasons have had more, at 14 and 15 hurricanes respectively. Despite the high number of hurricanes, not one hurricane hit the United States making the season the only season with 10 or more hurricanes without a United States landfall. The overall tropical cyclone count in the Atlantic exceeded that in the West Pacific for only the second time on record. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30, dates that conventionally delimit the period during each year when tropical cyclone formation is most likely. The first cyclone, Alex intensified into the first June hurricane since Allison in 1995. The month of September featured eight named storms. October featured five hurricanes, including Tomas, which became the latest on record in a calendar year to move through the Windward Islands. Activity was represented with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) value of 165 units, which was the eleventh highest value on record at the time. The activity in 2010 was heightened due to a very strong La Niña, which also led to an inactive Pacific hurricane season.

The 2015 Pacific hurricane season is the second-most active Pacific hurricane season on record, with 26 named storms, only behind the 1992 season. A record-tying 16 of those storms became hurricanes, and a record 11 storms further intensified into major hurricanes throughout the season. The Central Pacific, the portion of the Northeast Pacific Ocean between the International Date Line and the 140th meridian west, had its most active year on record, with 16 tropical cyclones forming in or entering the basin. Moreover, the season was the third-most active season in terms of accumulated cyclone energy, amassing a total of 290 units. The season officially started on May 15 in the Eastern Pacific and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Northeast Pacific basin. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year. This was shown when a tropical depression formed on December 31. The above-average activity during the season was attributed in part to the very strong 2014–16 El Niño event.

The 2016 Pacific hurricane season was tied as the fifth-most active Pacific hurricane season on record, alongside the 2014 season. Throughout the course of the year, a total of 22 named storms, 13 hurricanes and six major hurricanes were observed within the basin. Although the season was very active, it was considerably less active than the previous season, with large gaps of inactivity at the beginning and towards the end of the season. It officially started on May 15 in the Eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific ; they both ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in these regions of the Pacific Ocean. However, tropical development is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the formation of Hurricane Pali on January 7, the earliest Central Pacific tropical cyclone on record. After Pali, however, no tropical cyclones developed in either region until a short-lived depression on June 6. Also, there were no additional named storms until July 2, when Tropical Storm Agatha formed, becoming the latest first-named Eastern Pacific tropical storm since Tropical Storm Ava in 1969.

The 2016 Atlantic hurricane season was the deadliest Atlantic hurricane season since 2008, and the first above-average hurricane season since 2012, producing 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes and 4 major hurricanes. The season officially started on June 1 and ended on November 30, though the first storm, Hurricane Alex which formed in the Northeastern Atlantic, developed on January 12, being the first hurricane to develop in January since 1938. The final storm, Otto, crossed into the Eastern Pacific on November 25, a few days before the official end. Following Alex, Tropical Storm Bonnie brought flooding to South Carolina and portions of North Carolina. Tropical Storm Colin in early June brought minor flooding and wind damage to parts of the Southeastern United States, especially Florida. Hurricane Earl left 94 fatalities in the Dominican Republic and Mexico, 81 of which occurred in the latter. In early September, Hurricane Hermine, the first hurricane to make landfall in Florida since Hurricane Wilma in 2005, brought extensive coastal flooding damage especially to the Forgotten and Nature coasts of Florida. Hermine was responsible for five fatalities and about $550 million (2016 USD) in damage.

Tropical Storm Andrea brought flooding to Cuba, the Yucatan Peninsula, and portions of the East Coast of the United States in June 2013. The first tropical cyclone and named storm of the annual hurricane season, Andrea originated from an area of low pressure in the eastern Gulf of Mexico on June 5. Despite strong wind shear and an abundance of dry air, the storm strengthened while initially heading north-northeastward. Later on June 5, it re-curved northeastward and approached the Big Bend region of Florida. Andrea intensified and peaked as a strong tropical storm with winds at 65 mph (105 km/h) on June 6. A few hours later, the storm weakened slightly and made landfall near Steinhatchee, Florida later that day. It began losing tropical characteristics while tracking across Florida and Georgia. Andrea transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over South Carolina on June 7, though the remnants continued to move along the East Coast of the United States, until being absorbed by another extratropical system offshore Maine on June 10.

Tropical Storm Bonnie was a weak but persistent tropical cyclone that brought heavy rains to the Southeastern United States in May 2016. The second storm of the season, Bonnie formed from an area of low pressure northeast of the Bahamas on May 27, a few days before the official hurricane season began on June 1. Moving steadily west-northwestwards, Bonnie intensified into a tropical storm on May 28 and attained peak winds six hours later. However, due to hostile environmental conditions, Bonnie weakened to a depression hours before making landfall just east of Charleston, South Carolina, on May 29. Steering currents collapsed afterwards, causing the storm to meander over South Carolina for two days. The storm weakened further into a post-tropical cyclone on May 31, before emerging off the coast while moving generally east-northeastwards. On June 2, Bonnie regenerated into a tropical depression just offshore North Carolina as conditions became slightly more favorable. The next day, despite increasing wind shear and cooling sea surface temperatures, Bonnie reintensified into a tropical storm and reached its peak intensity. The storm hung on to tropical storm strength for another day, before weakening into a depression late on June 4 and became post-tropical early the next day.

Hurricane Hermine was the first hurricane to make landfall in Florida since Hurricane Wilma in 2005, and the first to develop in the Gulf of Mexico since Hurricane Ingrid in 2013. The ninth tropical depression, eighth named storm, and fourth hurricane of the 2016 Atlantic hurricane season, Hermine developed in the Florida Straits on August 28 from a long-tracked tropical wave. The precursor system dropped heavy rainfall in portions of the Caribbean, especially the Dominican Republic and Cuba. In the former, the storm damaged more than 200 homes and displaced over 1,000 people. Although some areas of Cuba recorded more than 12 in (300 mm) of rain, the precipitation was generally beneficial due to a severe drought. After being designated on August 29, Hermine shifted northeastwards due to a trough over Georgia and steadily intensified into an 80 mph (130 km/h) Category 1 hurricane just before making landfall in the Florida Panhandle during September 2. After moving inland, Hermine quickly weakened and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 3 near the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The remnant system meandered offshore the Northeastern United States before dissipating over southeastern Massachusetts on September 8.

The 2021 Atlantic hurricane season was the third-most active Atlantic hurricane season on record in terms of number of tropical cyclones, although many of them were weak and short-lived. With 21 named storms forming, it became the second season in a row and third overall in which the designated 21-name list of storm names was exhausted. Seven of those storms strengthened into a hurricane, four of which reached major hurricane intensity, which is slightly above-average. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period in each year when most Atlantic tropical cyclones form. However, subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the development of Tropical Storm Ana on May 22, making this the seventh consecutive year in which a storm developed outside of the official season.

The 2022 Atlantic hurricane season was a very destructive Atlantic hurricane season, which had an average number of named storms, a slightly above-average number of hurricanes, a slightly below-average number of major hurricanes, and a near-average accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index. Despite this, it became the third-costliest Atlantic hurricane season on record, behind only 2017 and 2005, mostly due to Hurricane Ian. The season officially began on June 1, and ended on November 30. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis occurs in the Atlantic Ocean. This year's first Atlantic named storm, Tropical Storm Alex, developed five days after the start of the season, making this the first season since 2014 not to have a pre-season named storm.

The 2021 Pacific hurricane season was a moderately active Pacific hurricane season, with above-average activity in terms of number of named storms, but below-average activity in terms of major hurricanes, as 19 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes formed in all. It also had a near-normal accumulated cyclone energy (ACE). The season officially began on May 15, 2021 in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, and on June 1, 2021, in the Central Pacific in the Northern Hemisphere. The season ended in both regions on November 30, 2021. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in these regions of the Pacific and are adopted by convention. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year, as illustrated by the formation of Tropical Storm Andres on May 9, which was the earliest forming tropical storm on record in the Eastern Pacific. Conversely, 2021 was the second consecutive season in which no tropical cyclones formed in the Central Pacific.

The 2022 Pacific hurricane season was an active hurricane season in the eastern North Pacific basin, with nineteen named storms, ten hurricanes, and four major hurricanes. Two of the storms crossed into the basin from the Atlantic. In the central North Pacific basin, no tropical cyclones formed. The season officially began on May 15 in the eastern Pacific, and on June 1 in the central; both ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in these regions of the Pacific and are adopted by convention.

Hurricane Dolores was a powerful and moderately damaging tropical cyclone whose remnants brought record-breaking heavy rains and strong winds to California. The seventh named storm, fourth hurricane, and third major hurricane of the record-breaking 2015 Pacific hurricane season, Dolores formed from a tropical wave on July 11. The system gradually strengthened, attaining hurricane status on July 13. Dolores rapidly intensified as it neared the Baja California peninsula, finally peaking as a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale with winds of 130 mph (215 km/h) on July 15. An eyewall replacement cycle began and cooler sea-surface temperatures rapidly weakened the hurricane, and Dolores weakened to a tropical storm two days later. On July 18, Dolores degenerated into a remnant low west of the Baja California peninsula.

Tropical Storm Danny was a weak and short-lived tropical cyclone that caused minor damage to the U.S. states of South Carolina and Georgia. The fourth named storm of the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season, the system formed from an area of low-pressure that developed from an upper-level trough over the central Atlantic Ocean on June 22. Moving west-northwestward, the disturbance gradually developed as convection, or showers and thunderstorms, increased over it. Although it was moving over the warm Gulf Stream, the organization of the disturbance was hindered by strong upper-level wind shear. By 18:00 UTC of June 27, as satellite images showed a well-defined center and thunderstorms, the system was upgraded to a tropical depression by the National Hurricane Center (NHC). At 06:00 UTC on the next day, the system further strengthened into Tropical Storm Danny east-southeast of Charleston, South Carolina. Danny continued its track towards South Carolina while slowly strengthening, subsequently reaching its peak intensity at that day of 45 mph (72 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 1,009 mbar (29.8 inHg) at 18:00 UTC. Danny then made landfall in Pritchards Island, north of Hilton Head, in a slightly weakened state at 23:20 UTC on the same day, with winds of 40 mph (64 km/h) and indicating that Danny weakened prior to moving inland. The system then weakened to a tropical depression over east-central Georgia, before dissipating shortly afterward.

Tropical Storm Fred was a strong tropical storm which affected much of the Greater Antilles and the Southeastern United States in August 2021. The sixth tropical storm of the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season, Fred originated from a tropical wave first noted by the National Hurricane Center on August 4. As the wave drifted westward, advisories were initiated on the wave as a potential tropical cyclone by August 9 as it was approaching the Leeward Islands. Entering the Eastern Caribbean Sea after a close pass to Dominica by the next day, the potential tropical cyclone continued northwestward. By August 11, the disturbance had formed into Tropical Storm Fred just south of Puerto Rico, shortly before hitting the Dominican Republic on the island of Hispaniola later that day. The storm proceeded to weaken to a tropical depression over the highly mountainous island, before emerging north of the Windward Passage on August 12. The disorganized tropical depression turned to the west and made a second landfall in Northern Cuba on August 13. After having its circulation continuously disrupted by land interaction and wind shear, the storm degenerated into a tropical wave as it was turning northward near the western tip of Cuba the following day. Continuing north, the remnants of Fred quickly re-organized over the Gulf of Mexico, regenerating into a tropical storm by August 15. Fred continued towards the Florida Panhandle and swiftly intensified to a strong 65 mph (105 km/h) tropical storm before making landfall late on August 16 and moving into the state of Georgia. Afterward, Fred continued moving north-northeastward, before degenerating into an extratropical low on August 18. Fred's remnants later turned eastward, and the storm's remnants dissipated on August 20, near the coast of Massachusetts.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Eric S. Blake (January 20, 2017). Tropical Cyclone Report: Tropical Storm Julia (PDF) (Technical report). National Hurricane Center. pp. 2, 3. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (September 8, 2016). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ Todd B. Kimberlain (September 11, 2016). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ Stacy R. Stewart and James L. Franklin (September 14, 2016). "Tropical Storm Julia Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ Michael J. Brennan (September 15, 2016). "Tropical Depression Julia Discussion Number 6". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (September 17, 2016). "Tropical Depression Julia Discussion Number 13". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ Daniel P. Brown (September 18, 2016). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Julia Discussion Number 21". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ Philip Helsel (September 14, 2016). "Tropical Storm Julia Drenches Florida; Flash Flood Watches". NBC . Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tropical Storm Julia Knocks Out Power, Floods South Carolina Roads; Damage Reported Along Florida, Georgia Coasts". weather.com. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ↑ Event Details: Tropical Storm. National Weather Service Jacksonville, Florida (Report). National Climatic Data Center. 2016. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ↑ Chris Bonanno and J. D. Gallop (September 14, 2016). "Storm brings tornado to Brevard; now Tropical Storm Julia". Florida Today. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "N. Carolina flooding from Julia closes schools, spews sewage". News & Observer . Associated Press. September 23, 2016. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- 1 2 "McCrory declares State of Emergency for 11 flooded NC counties". WNCN . Raleigh, North Carolina. September 22, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ Amir Vera (September 27, 2016). "Gov. Pat McCrory lifts state of emergency for 11 North Carolina counties". The Virginian-Pilot . Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ Event Details: Flood. National Weather Service Wakefield, Virginia (Report). National Climatic Data Center. 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ Cal Bryant (October 13, 2016). "Bertie added to fed disaster declaration". Roanoke-Chowan News-Herald . Windsor, North Carolina. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ↑ Kevin Green (October 19, 2016). "December deadline set for disaster assistance from Julia flooding". WAVY-TV . Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- 1 2 "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. National Climatic Data Center. 58 (9): 18, 19, 109, 110, 111, 154, 155, 156, 201, 202, 243, and 244. September 2016. ISSN 0039-1972 . Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Storm Events Database: "Tropical Storm Julia"". National Centers for Environmental Information. 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

External links

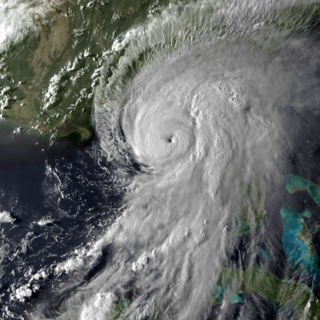

Tropical Storm Julia at peak intensity over Florida on September 13 |

Tropical cyclones of the 2016 Atlantic hurricane season | ||

|---|---|---|