The 2004 Atlantic hurricane season was a very deadly, destructive, and active Atlantic hurricane season, with over 3,200 deaths and more than $61 billion in damage. More than half of the 16 tropical cyclones brushed or struck the United States. Due to the development of a Modoki El Niño – a rare type of El Niño in which unfavorable conditions are produced over the eastern Pacific instead of the Atlantic basin due to warmer sea surface temperatures farther west along the equatorial Pacific – activity was above average. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30, though the season's last storm, Otto, dissipated on December 3, extending the season beyond its traditional boundaries. The first storm, Alex, developed offshore of the Southeastern United States on July 31, one of the latest dates on record to see the formation of the first system in an Atlantic hurricane season. It brushed the Carolinas and the Mid-Atlantic, causing one death and $7.5 million (2004 USD) in damage. Several storms caused only minor damage, including tropical storms Bonnie, Earl, Hermine, and Matthew. In addition, hurricanes Danielle, Karl, and Lisa, Tropical Depression Ten, Subtropical Storm Nicole and Tropical Storm Otto had no effect on land while tropical cyclones. The season was the first to exceed 200 units in accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) since 1995, mostly from Hurricane Ivan, the storm produced the highest ACE. Ivan generated the second-highest ACE in the Atlantic, only behind 1899 San Ciriaco Hurricane.

The 1999 Atlantic hurricane season was a fairly active season, mostly due to a persistent La Niña that developed in the latter half of 1998. It had five Category 4 hurricanes – the highest number recorded in a single season in the Atlantic basin, previously tied in 1933 and 1961, and later tied in 2005 and 2020. The season officially began on June 1, and ended on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. The first storm, Arlene, formed on June 11 to the southeast of Bermuda. It meandered slowly for a week and caused no impact on land. Other tropical cyclones that did not affect land were Hurricane Cindy, Tropical Storm Emily, and Tropical Depression Twelve. Localized or otherwise minor damage occurred from Hurricanes Bret, Gert, and Jose, and tropical storms Harvey and Katrina.

The 1998 Atlantic hurricane season was a catastrophic and deadly Atlantic hurricane season, featuring the highest number of storm-related fatalities in over 218 years and some of the costliest ever at the time. The season had above average activity, due to the dissipation of an El Niño event and transition to La Niña conditions. It officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30, dates which conventionally delimit the period during which most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic Ocean. The season had a rather slow start, with no tropical cyclones forming in June. The first tropical cyclone, Tropical Storm Alex, developed on July 27, and the season's final storm, Hurricane Nicole, became extratropical on December 1.

The 1992 Atlantic hurricane season was a significantly below average season for overall tropical or subtropical cyclones as only ten formed. Six of them became named tropical storms, and four of those became hurricanes; one hurricane became a major hurricane. The season was also near-average in terms of accumulated cyclone energy. The season officially started on June 1 and officially ended on November 30. However, tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by formation in April of an unnamed subtropical storm in the central Atlantic.

Tropical Storm Helene was a long-lived tropical cyclone that oscillated for ten days between a tropical wave and a 70 mph (110 km/h) tropical storm. It was the twelfth tropical cyclone and eighth tropical storm of the 2000 Atlantic hurricane season, forming on September 15 east of the Windward Islands. After degenerating into a tropical wave, the system produced flooding and mudslides in Puerto Rico. It reformed into a tropical depression on September 19 south of Cuba, and crossed the western portion of the island the next day while on the verge of dissipation. However, it intensified into a tropical storm in the Gulf of Mexico, reaching its peak intensity while approaching the northern Gulf Coast.

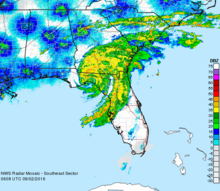

Tropical Storm Edouard was the first of eight named storms to form in September 2002, the most such storms in the North Atlantic for any month at the time. The fifth tropical storm of the 2002 Atlantic hurricane season, Edouard developed into a tropical cyclone on September 1 from an area of atmospheric convection associated with a cold front east of Florida. Under weak steering currents, Edouard drifted to the north and executed a clockwise loop to the west. Despite moderate to strong levels of wind shear, the storm reached a peak intensity of 65 mph (105 km/h) on September 3, but quickly weakened as it tracked westward. Edouard made landfall on northeastern Florida on September 5, and after crossing the state it dissipated on September 6 while becoming absorbed into the larger circulation of Tropical Storm Fay.

Tropical Storm Hermine was the eighth tropical cyclone and named storm of the 1998 Atlantic hurricane season. Hermine developed from a tropical wave that emerged from the west coast of Africa on September 5. The wave moved westward across the Atlantic Ocean, and on entering the northwest Caribbean interacted with other weather systems. The resultant system was declared a tropical depression on September 17 in the central Gulf of Mexico. The storm meandered north slowly, and after being upgraded to a tropical storm made landfall on Louisiana, where it quickly deteriorated into a tropical depression again on September 20.

The 2010 Atlantic hurricane season was the first of three consecutive very active Atlantic hurricane seasons, each with 19 named storms. This above average activity included 12 hurricanes, equaling the number that formed in 1969. Only the 2020 and 2005 seasons have had more, at 14 and 15 hurricanes respectively. Despite the high number of hurricanes, not one hurricane hit the United States making the season the only season with 10 or more hurricanes without a United States landfall. The overall tropical cyclone count in the Atlantic exceeded that in the West Pacific for only the second time on record. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30, dates that conventionally delimit the period during each year when tropical cyclone formation is most likely. The first cyclone, Alex intensified into the first June hurricane since Allison in 1995. The month of September featured eight named storms. October featured five hurricanes, including Tomas, which became the latest on record in a calendar year to move through the Windward Islands. Activity was represented with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) value of 165 units, which was the eleventh highest value on record at the time. The activity in 2010 was heightened due to a very strong La Niña, which also led to an inactive Pacific hurricane season.

The 2012 Atlantic hurricane season was the final year in a string of three consecutive very active seasons since 2010, with 19 tropical storms. The 2012 season was also a costly one in terms of property damage, mostly due to Hurricane Sandy. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30, dates that conventionally delimit the period during each year in which most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic Ocean. However, Alberto, the first named system of the year, developed on May 19 – the earliest date of formation since Subtropical Storm Andrea in 2007. A second tropical cyclone, Beryl, developed later that month. This was the first occurrence of two pre-season named storms in the Atlantic basin since 1951. It moved ashore in North Florida on May 29 with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h), making it the strongest pre-season storm to make landfall in the Atlantic basin. This season marked the first time since 2009 where no tropical cyclones formed in July. Another record was set by Hurricane Nadine later in the season; the system became the fourth-longest-lived tropical cyclone ever recorded in the Atlantic, with a total duration of 22.25 days. The final storm to form, Tony, dissipated on October 25 – however, Hurricane Sandy, which formed before Tony, became extratropical on October 29.

Tropical Storm Hermine was a near-hurricane strength tropical cyclone that brought widespread flooding from Guatemala northwards to Oklahoma in early September 2010. Though it was named in the western Gulf of Mexico, Hermine developed directly from the remnant low-pressure area associated with the short-lived Tropical Depression Eleven-E in the East Pacific. Throughout its lifespan, the storm caused 52 direct deaths and roughly US$740 million in damage to crops and infrastructure, primarily in Guatemala. The precursor tropical depression formed on September 3 in the Gulf of Tehuantepec and neared tropical storm intensity before making landfall near Salina Cruz, Mexico, on the next day. Though the depression quickly weakened to a remnant low, the disturbance crossed the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and tracked north into the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico, where it reorganized into a tropical cyclone once again on September 5. There, the system quickly strengthened into a tropical storm and received the name Hermine before moving ashore near Matamoros, Mexico on September 7 as a high-end tropical storm. Over the next few days, Hermine weakened as it moved over the U.S. Southern Plains, eventually dissipating over Kansas on September 10.

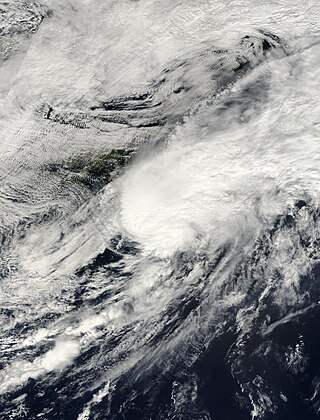

Hurricane Katia was a fairly intense Cape Verde hurricane that had substantial impact across Europe as a post-tropical cyclone. The eleventh named storm, second hurricane, and second major hurricane of the active 2011 Atlantic hurricane season, Katia originated as a tropical depression from a tropical wave over the eastern Atlantic on August 29. It intensified into a tropical storm the following day and further developed into a hurricane by September 1, although unfavorable atmospheric conditions hindered strengthening thereafter. As the storm began to recurve over the western Atlantic, a more hospitable regime allowed Katia to become a major hurricane by September 5 and peak as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) that afternoon. Internal core processes, increased wind shear, an impinging cold front, and increasingly cool ocean temperatures all prompted the cyclone to weaken almost immediately after peak, and Katia ultimately transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 10.

Tropical Storm Beryl was the strongest off-season Atlantic tropical cyclone on record to make landfall in the United States. The second tropical cyclone of the 2012 Atlantic hurricane season, Beryl developed on May 26 from a low-pressure system offshore North Carolina. Initially subtropical, the storm slowly acquired tropical characteristics as it tracked across warmer sea surface temperatures and within an environment of decreasing vertical wind shear. Late on May 27, Beryl transitioned into a tropical cyclone less than 120 miles (190 km) from North Florida. Early the following day, the storm moved ashore near Jacksonville Beach, Florida, with peak winds of 65 mph (100 km/h). It quickly weakened to a tropical depression, dropping heavy rainfall while moving slowly across the southeastern United States. A cold front turned Beryl to the northeast, and the storm became extratropical on May 30.

The 2016 Atlantic hurricane season was the first above-average hurricane season since 2012, producing 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes and 4 major hurricanes. The season officially started on June 1 and ended on November 30, though the first storm, Hurricane Alex which formed in the Northeastern Atlantic, developed on January 12, being the first hurricane to develop in January since 1938. The final storm, Otto, crossed into the Eastern Pacific on November 25, a few days before the official end. Following Alex, Tropical Storm Bonnie brought flooding to South Carolina and portions of North Carolina. Tropical Storm Colin in early June brought minor flooding and wind damage to parts of the Southeastern United States, especially Florida. Hurricane Earl left 94 fatalities in the Dominican Republic and Mexico, 81 of which occurred in the latter. In early September, Hurricane Hermine, the first hurricane to make landfall in Florida since Hurricane Wilma in 2005, brought extensive coastal flooding damage especially to the Forgotten and Nature coasts of Florida. Hermine was responsible for five fatalities and about $550 million (2016 USD) in damage.

The 2019 Atlantic hurricane season was the fourth consecutive above-average and damaging season dating back to 2016. The season featured eighteen named storms, however, many storms were weak and short-lived, especially towards the end of the season. Six of those named storms achieved hurricane status, while three intensified into major hurricanes. Two storms became Category 5 hurricanes, marking the fourth and final consecutive season with at least one Category 5 hurricane, the third consecutive season to feature at least one storm making landfall at Category 5 intensity, and the seventh on record to have multiple tropical cyclones reaching Category 5 strength. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin and are adopted by convention. However, tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the formation of Subtropical Storm Andrea on May 20, making this the fifth consecutive year in which a tropical or subtropical cyclone developed outside of the official season.

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record, in terms of number of systems. It featured a total of 31 tropical or subtropical cyclones, with all but one cyclone becoming a named storm. Of the 30 named storms, 14 developed into hurricanes, and a record-tying seven further intensified into major hurricanes. It was the second and final season to use the Greek letter storm naming system, the first being 2005, the previous record. Of the 30 named storms, 11 of them made landfall in the contiguous United States, breaking the record of nine set in 1916. During the season, 27 tropical storms established a new record for earliest formation date by storm number. This season also featured a record ten tropical cyclones that underwent rapid intensification, tying it with 1995, as well as tying the record for most Category 4 hurricanes in a singular season in the Atlantic Basin. This unprecedented activity was fueled by a La Niña that developed in the summer months of 2020, continuing a stretch of above-average seasonal activity that began in 2016. Despite the record-high activity, this was the first season since 2015 in which no Category 5 hurricanes formed.

Tropical Storm Andrea brought flooding to Cuba, the Yucatan Peninsula, and portions of the East Coast of the United States in June 2013. The first tropical cyclone and named storm of the annual hurricane season, Andrea originated from an area of low pressure in the eastern Gulf of Mexico on June 5. Despite strong wind shear and an abundance of dry air, the storm strengthened while initially heading north-northeastward. Later on June 5, it re-curved northeastward and approached the Big Bend region of Florida. Andrea intensified and peaked as a strong tropical storm with winds at 65 mph (105 km/h) on June 6. A few hours later, the storm weakened slightly and made landfall near Steinhatchee, Florida later that day. It began losing tropical characteristics while tracking across Florida and Georgia. Andrea transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over South Carolina on June 7, though the remnants continued to move along the East Coast of the United States, until being absorbed by another extratropical system offshore Maine on June 10.

Tropical Storm Colin was the earliest third named storm in the Atlantic basin on record for four years, until it was surpassed by Tropical Storm Cristobal in 2020. An atypical, poorly organized tropical cyclone, Colin developed from a low pressure area over the Gulf of Mexico near the northern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula late on June 5, 2016. Moving northward, the depression strengthened into a tropical storm about eight hours after its formation. On June 6, Colin curved to the north-northeast and intensified slightly to winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). Strong wind shear prevented further strengthening and resulted in the system maintaining a disheveled appearance on satellite imagery. Later, the storm began accelerating to the northeast. Early on June 7, Colin made landfall in rural Taylor County, Florida, still at peak intensity. The system rapidly crossed northern Florida and emerged into the Atlantic Ocean several hours later. By late on June 7, Colin transitioned into an extratropical cyclone offshore North Carolina before being absorbed by a frontal boundary the following day.

Tropical Storm Julia was a weak tropical cyclone that caused minor damage across the Eastern United States in September 2016. The tenth named storm of the 2016 Atlantic hurricane season, Julia developed from a tropical wave near the coast of east-central Florida on September 13. Initially a tropical depression, the system soon made landfall near Jensen Beach. Despite moving inland, the cyclone intensified into a tropical storm, shortly before strengthening further to reach maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h). Julia then drifted north-northwestward and then northeastward, moving offshore the Southeastern United States on September 14. A cyclonic loop occurred as strong westerly air developed in the region, with the shear causing fluctuations in intensity. By September 19, Julia degenerated into a remnant low, which later transitioned into an extratropical cyclone and moved inland over North Carolina before dissipating on September 21.

The 2021 Atlantic hurricane season was the third-most active Atlantic hurricane season on record in terms of number of tropical cyclones, although many of them were weak and short-lived. With 21 named storms forming, it became the second season in a row and third overall in which the designated 21-name list of storm names was exhausted. Seven of those storms strengthened into a hurricane, four of which reached major hurricane intensity, which is slightly above-average. The season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30. These dates historically describe the period in each year when most Atlantic tropical cyclones form. However, subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the development of Tropical Storm Ana on May 22, making this the seventh consecutive year in which a storm developed outside of the official season.

The 2022 Atlantic hurricane season was a very destructive and deadly Atlantic hurricane season. Despite having an average number of named storms, it became the third-costliest Atlantic hurricane season on record, behind only 2017 and 2005, mostly due to Hurricane Ian, which also became the 1st Category 5 hurricane in the Atlantic since 2019. The season officially began on June 1, and ended on November 30. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis occurs in the Atlantic Ocean. This year's first Atlantic named storm, Tropical Storm Alex, developed five days after the start of the season, making this the first season since 2014 not to have a pre-season named storm.