Groveland case

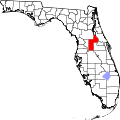

In 1949 four young African-American men (Samuel Shepherd, Walter Irvin, Charles Greenlee, and Ernest Thomas) were charged with raping a 17-year-old white farm girl in Groveland, Florida. They were convicted by an all-white jury. The case was appealed to the Florida Supreme Court which found that:

Two witnesses for the State testified as to the identity of the four [men]. From the description of the automobile as given by the two witnesses the same was later located. The three defendants testified they were driving the car in question during the same hours of the early morning except they were driving in the Orlando area, which was in the opposite direction. [11]

In addition to the eyewitness testimony, there was physical evidence linking the car in which the young men were riding to the crime. The Florida Supreme Court stated:

Near the scene of the crime a handkerchief and some cotton were found. The woman was found near the scene of the crime about dawn. A large track about the scene fit the shoe of one of the appellants. Cotton or lint about the car and broken glass in the automobile testified to by the woman assisted the officers in identifying the car which the appellants admit they were riding in at the exact hour the State charge the crime was committed. [11]

The victim testified that she had known Shepherd for years and that Irvin was someone she had seen in and around the Groveland community before the night of the assault. She reported the rape to the police within five hours after it occurred. One of the three men she accused (Thomas) was shot and killed by the police during his arrest.

After the Florida Supreme Court decided to uphold the guilty verdicts, the United States Supreme Court agreed to hear the case.

Attorney Thurgood Marshall, then the special counsel with the NAACP's Legal Defense Fund, represented the four men, on the briefs, taking their case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Oral argument was conducted by attorney Franklin H. Williams. The Supreme Court overturned the guilty verdicts. The Court found that sensational headlines in the local papers ("Night Riders Burn Lake Negro Homes" and "Flames From Negro Homes Light Night Sky in Lake County"), and newspaper reports of the sheriff's statement that the young men had confessed while in custody, resulted in an unfair trial. "These defendants were prejudged as guilty and the trial was but a legal gesture to register a verdict already dictated by the press and the public opinion which it generated." A new trial was ordered. [12]

In 1949, Harry T. Moore, the executive director of the Florida NAACP, organized a campaign against the conviction of the Groveland Four. Soon afterward, Sheriff Willis V. McCall of Lake County, Florida, shot Shepherd and Irvin. He asserted that they were trying to escape. Shepherd was killed, and Irvin was seriously wounded. When Irvin recovered, he told investigators that the sheriff had shot the two prisoners, without provocation, while they were in handcuffs.

Moore demanded that the sheriff be indicted for murder and requested that the Governor suspend McCall from office. On December 25, 1951, a bomb exploded in Moore's house, killing him and his wife, Harriette.

Some alleged that Sheriff McCall was associated with ordering this bombing; however, an extensive FBI investigation at the time and additional separate investigations have failed to produce any evidence supporting allegations of McCall's involvement.

Although members of the Ku Klux Klan were suspected of the crime, the people responsible were never brought to trial. [13]

In 2016, the City of Groveland and Lake County each apologized to survivors of the four men for the injustice against them. On April 18, 2017, a resolution of the Florida House of Representatives requested that all four men be exonerated. [14] The Florida Senate quickly passed a similar resolution; lawmakers called on Governor Rick Scott to officially pardon the men. On January 11, 2019, the Florida Board of Executive Clemency voted to pardon the Groveland Four. [15] Newly elected Governor Ron DeSantis subsequently did so. On November 22, 2021, Judge Heidi Davis granted the state's motion to posthumously exonerate the men. [16]