Geology

The Vale Formation is named after a former post office in the vicinity of Ballinger in Runnels County. [1] At its broadest conception, the Vale Formation is a unit of primarily terrestrial sediments up to 160 metres (520 ft) thick, [2] stretching from the Texas-Oklahoma border at Wilbarger County, as far south as Runnels County. The base of the Vale Formation is marked by either a limestone bed (the Standpipe Limestone, south of Abilene), or in some northern areas, a sharp unconformity. Likewise, its contact with the Choza Formation is marked by the base of the Bullwagon Dolomite, which is most well-exposed south of Haskell, or by evaporite beds in northern exposures such as Knox County. [3] [1]

Limestone is rare in the fully terrestrial northern red beds, complicating the distinction between the three formations of the Clear Fork Group. [3] To resolve this problem, some geologists, like Nelson et al. (2013), consider the northern part of the Clear Fork Group to be a single formation divided into three informal subunits. [2] In the northern area, major sandstone beds are the most useful stratigraphic markers for distinguishing these informal subunits. The Middle Clear Fork Formation extends from the base of the Brushy Creek Sandstone to the base of the Rt. 1919 Sandstone. Another major sandstone bed, the Cedar Top Sandstone, occurs between these two levels. [2]

As with much of the Texas red beds, the dominant sediments (around 80% by volume) are fine-grained red floodplain deposits such as mudstones, clays, shales, siltstones, and paleosols. Localized beds and lenses of sandstone and conglomerate recorded active meandering river channels, abandoned channels (such as oxbow lakes), and crevasse splays. [3] [1] [4] [2] [5] [6] The conglomerates of the Vale Formation occur in two distinct forms, either large light-colored fragments or (particularly in the northern area) dark brown pebbles derived from the surrounding clay. [3] [7] Light even-bedded clay (pond deposits) may occasionally be found. [3] [1] [2] [8]

Though quite fossiliferous, the fossils of the Vale Formation have not been studied as long as older parts of the Texas red beds, some of which have been prospected since the 1870s. Geologists of the University of Texas discovered the first fossils from the Vale Formation in the 1930s, at the Sid McAdams locality in Taylor County. [9] [1] Since 1946, many more finds were recovered from Knox, Baylor, and Foard counties under the direction of University of Chicago paleontologist Everett C. Olson, who described the northern Vale fossil fauna in detail over the course of the 1950s. [10] [3] [1] Other notable sites include the Stamford locality in Haskell County (discovered by Dalquest and Maymay in 1963), [11] [1] the Blackwood locality in Taylor County (discovered by David Berman in 1970), [1] and the Mud Hill locality (described by Bryan Gee et al. in 2018), also in Taylor County. [12] Over 60 small fossil sites are scattered south of the Clear Fork of the Brazos River. [1]

Paleobiota

Synapsids

| Synapsids of the Vale Formation |

|---|

| Genus | Species | Notes | Images |

|---|

| Casea | C. broilii | A medium-sized caseid. [13] Well-preserved fossils of this species are concentrated within the Cacops bonebed in Baylor County, which may belong to either the upper Arroyo or lower Vale formation. [14] [15] [1] |  |

| "C." nicholsi [14] | A rare medium-sized caseid, similar to C. broilii but with a larger head, torso, and forelimbs. Known from two closely associated partial skeletons from the upper part of the Vale Formation in Knox County. [14] [15] [1] Phylogenetic analyses suggest that this species is not closely related to Casea broilii, but its fossil material is too fragmentary to warrant a new genus. [16] [17] [18] | |

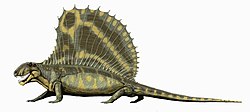

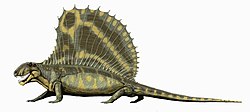

| Dimetrodon | D. giganhomogenes | A large and fairly common sail-backed sphenacodontid known from various isolated remains and a few partial skeletons which are most similar to Dimetrodon giganhomogenes from the Arroyo Formation. One of the more common fossils of the Sid McAdams and Blackwood localities, with at least 22 individuals from the former site. [1] This species is often misspelled as Dimetrodon gigashomogenes. [13] [19] [3] |  |

| Ophiacodon? | O.? sp. | A very rare possible ophiacodontid, based on a small humerus from the Sid McAdams locality. If legitimate, it may have been the last surviving member of its family. The next youngest ophiacodontid is Varanosaurus , from the Arroyo Formation. [1] | |

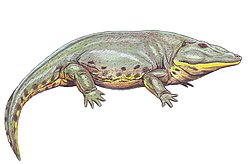

| Varanops | V. brevirostris | A large varanopid. [13] Most fossils of this species are concentrated within the Cacops bonebed in Baylor County, which may belong to either the upper Arroyo or lower Vale formation. [1] In addition, an articulated partial skeleton is known from the Mud Hill locality. [20] [21] [12] |  |

Amphibians

An indeterminate hapsidopareiid microsaur is known from the Mud Hill locality. It is potentially one of the youngest known microsaurs, apart from a few rhynchonkids known from Choza-equivalent strata near Norman, Oklahoma. [12]

| Amphibians of the Vale Formation |

|---|

| Genus | Species | Notes | Images |

|---|

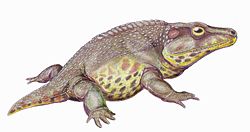

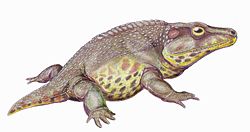

| Cacops | cf. C. aspidephorus | A eucacopine dissorophid. Well-preserved fossils of Cacops aspidephorus are concentrated within the Cacops bonebed in Baylor County, which may belong to either the upper Arroyo or lower Vale formation. [1] One particularly large partial skeleton is known a site in Baylor County which is assigned to the Vale Formation with more certainty. This larger individual was originally named as a new trematopid species, Trematopsis seltini . [29] [30] [31] |  |

| Diadectes | D. sp. | An uncommon diadectid diadectomorph, with only a few fossils persisting into the lower part of the formation. [23] [1] [12] |  |

| Diplocaulus | D. magnicornis | A diplocaulid nectridean with robust blunt-tipped horns. Very common in pond sediments in the lower part of the formation, but not present in subsequent layers, which may indicate extinction via climate change or replacement by potential descendants such as D. recurvatus. [32] [1] |  |

| D. recurvatus [32] | A diplocaulid nectridean with bent horns tapering to a sharp point. One of the most common fossils in stream sediments from the middle-upper part of the formation, [32] [12] with "literally hundreds" [11] [1] known from the Stamford locality, and many from the Blackwood locality as well. [1] |

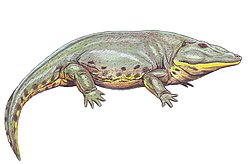

| Eryops | E. megacephalus | A large eryopid temnospondyl, [27] locally common at a few sites such as the Blackwood locality. [1] |  |

| Gerobatrachus? [33] | G. hottoni [33] | A small amphibamiform known from a partial skeleton. One of the Paleozoic amphibians most similar to lissamphibians (modern amphibians such as frogs, salamanders, and caecilians). [33] Its locality in Baylor County is from the lower half of the Clear Fork Group (Arroyo or Vale formation). |  |

| Lysorophus | L. tricarinatus | A widespread and locally abundant lysorophian, a type of elongated microsaur predominantly found aestivating in lakeside burrows. [34] [1] The validity of this genus and species has been questioned, and it may be regarded as a junior synonym of Brachydectes . [35] [36] [37] |  |

| Peronedon | P. primus | A small "keraterpetontid" (diplocaulid) nectridean which is only found at a few particular sites. [38] [1] | |

| Seymouria | S. baylorensis | A large seymouriamorph, mostly known from vertebrae and hindlimb material found at the Sid McAdams locality. [1] |  |

| S. grandis [39] | A large seymouriamorph known from skeletal material found at the Blackwood locality. These fossils were previously misattributed to Labidosaurikos meachami. [39] [1] | |

| Tersomius? | T.? sp. | Various tooth-bearing dissorophid skull fragments from the Sid McAdams locality, similar to Tersomius and Broiliellus . [1] | |

| Trimerorhachis | T. insignis | An aquatic dvinosaur which is very common at most sites. [40] [41] [1] [42] |  |

| T. cf. mesops | A dvinosaur skull from the Stamford locality with several traits (longer snout, absence of an intertemporal bone) comparable to Trimerorhachis mesops. [1] [42] | |

| Waggoneria [27] | W. knoxensis [27] | An uncommon and enigmatic tetrapod with thick vertebrae, a broad otic notch, and multiple rows of teeth on the lower jaw. Its original description compared it to Seymouria, Diadectes, Procolophon , and Labidosaurus , tentatively labeling it as a seymouriamorph. [27] | |

Plants

Plant fossils of the middle Clear Fork are most well-preserved in fine-grained abandoned river channel deposits. [4] Some abandoned channel sites are dominated by walchian conifers, Taeniopteris , and "comioid" peltasperms ( Auritifolia ). [8] Others have a high proportion of woody gigantopterids ( Evolsonia ), Taeniopteris, and marattialean tree ferns. [6] Tree ferns were probably most specialized for swampy areas alongside permanent water, while conifers occupied dry uplands. Peltasperms and gigantopterids were accustomed to intermediate conditions: well-drained soils with a high water table. [8] [6] A diverse array of insect damage is reported from leaf fossils, with particular preference towards Auritifolia and Taniopteris. [44]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.