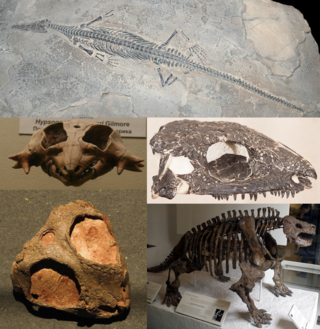

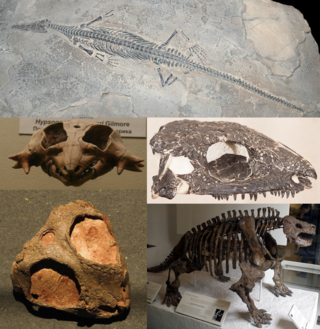

Parareptilia ("near-reptiles") is an extinct subclass or clade of basal sauropsids/reptiles, typically considered the sister taxon to Eureptilia. Parareptiles first arose near the end of the Carboniferous period and achieved their highest diversity during the Permian period. Several ecological innovations were first accomplished by parareptiles among reptiles. These include the first reptiles to return to marine ecosystems (mesosaurs), the first bipedal reptiles, the first reptiles with advanced hearing systems, and the first large herbivorous reptiles. The only parareptiles to survive into the Triassic period were the procolophonoids, a group of small generalists, omnivores, and herbivores. The largest family of procolophonoids, the procolophonids, rediversified in the Triassic, but subsequently declined and became extinct by the end of the period.

The Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone is a tetrapod assemblage zone or biozone which correlates to the upper Adelaide and lower Tarkastad Subgroups of the Beaufort Group, a fossiliferous and geologically important geological Group of the Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. This biozone has outcrops in the south central Eastern Cape and in the southern and northeastern Free State. The Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone is one of eight biozones found in the Beaufort Group, and is considered to be Early Triassic in age.

Procolophonidae is an extinct family of small, lizard-like parareptiles known from the Late Permian to Late Triassic that were distributed across Pangaea, having been reported from Europe, North America, China, South Africa, South America, Antarctica and Australia. The most primitive procolophonids were likely insectiovous or omnivorous, more derived members of the clade developed bicusped molars, and were likely herbivorous feeding on high fiber vegetation or durophagous omnivores. Many members of the group are noted for spines projecting from the quadratojugal bone of the skull, which likely served a defensive purpose as well as possibly also for display. At least some taxa were likely fossorial burrowers. While diverse during the Early and Middle Triassic, they had very low diversity during the Late Triassic, and were extinct by the beginning of the Jurassic.

Leptopleuron is an extinct genus of procolophonid that lived in the dry lands during the late Triassic in Elgin of northern Scotland and was the first to be included in the clade of Procolophonidae. First described by English paleontologist and biologist Sir Richard Owen, Leptopleuron is derived from two Greek bases, leptos for "slender" and pleuron for "rib," describing it as having slender ribs. The fossil is also known by a second name, Telerpeton, which is derived from the Greek bases tele for "far off" and herpeton for "reptile." In Scotland, Leptopleuron was found specifically in the Lossiemouth Sandstone Formation. The yellow sandstone it was located in was poorly lithified with wind coming from the southwest. The environment is also described to consist of barchan dunes due to the winds, ranging up to 20 m tall that spread during dry phases into flood plains. Procolophonoids such as Leptopleuron were considered an essential addition to the terrestrial ecosystem during the Triassic.

Sclerosaurus is an extinct genus of procolophonid parareptile known from the Early to Middle Triassic of Germany and Switzerland. It contains a single species, Sclerosaurus armatus. It was fairly small, about 30 cm long, distinguished from other known parareptiles by the possession of long, backwardly projecting spikes, rear lower jaw teeth with slightly imbricating crowns, and a narrow band of back armor comprising two or three rows of sculptured osteoderms on either side of the midline.

Colobomycter is an extinct genus of lanthanosuchoid parareptile known from the Early Permian of Oklahoma.

Owenetta is an extinct genus of owenettid procolophonian parareptile. Fossils have been found from the Beaufort Group in the Karoo Basin of South Africa. Although most procolophonians lived during the Triassic, Owenetta existed during the Wuchiapingian and Changhsingian stages of the Late Permian as well as the early Induan stage of the Early Triassic. It is the type genus of the family Owenettidae, and can be distinguished from other related taxa in that the posterior portion of the supratemporal bears a lateral notch and that the pineal foramen is surrounded by a depressed parietal surface on the skull table.

Owenettidae is an extinct family of procolophonian parareptiles. Fossils have been found primarily from Africa and Madagascar, with one genus present from South America. It is the sister taxon to the family Procolophonidae. Modesto and Damiani (2007) defined Owenettidae as a stem-based group including Owenetta rubidgei and all species closely related to it than to Procolophon trigoniceps.

Procolophonoidea is an extinct superfamily of procolophonian parareptiles. Members were characteristically small, stocky, and lizard-like in appearance. Fossils have been found worldwide from many continents including Antarctica. The first members appeared during the Late Permian in the Karoo Basin of South Africa.

Phonodus is an extinct genus of procolophonid parareptile. It is known from a single skull found from the Early Triassic Katberg Formation in South Africa. It is the oldest known member of the subfamily Leptopleuroninae, and was likely the result of a procolophonid migration into the Karoo Basin from Laurasia after the Permo-Triassic extinction event. Because Phonodus had large maxillary teeth underneath a large antorbital buttress, and a lack of ventral temporal emargination along the side of the skull, it probably had a durophagous diet.

Kitchingnathus is an extinct genus of basal procolophonid parareptile from Early Triassic deposits of Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. It is known from the holotype BP/1/1187, skull and partial postcranium, which was first assigned to the more derived Procolophon trigoniceps. It was collected by the South African palaeontologist, James W. Kitching in October 1952 from Hobbs Hill, west of Cathcart. It was found in the middle or upper part of the Katberg Formation of the Beaufort Group and referred to the uppermost Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone. It was first named by Juan Carlos Cisneros in 2008 and the type species is Kitchingnathus untabeni. The generic name honours James W. Kitching, and "gnathus", from Greek gnathos meaning mandible. The specific name meaning "from the hill", in isiZulu, is in reference to the locality where the fossil was found.

Sauropareion is an extinct genus of basal procolophonid parareptile from earliest Triassic deposits of Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. It is known from the holotype SAM PK-11192, skull and partial postcranium. It was collected by the late L. D. Boonstra in 1935 from Barendskraal in the Middelburg District and referred to the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Beaufort Group. It was first named by Sean P. Modesto, Hans-Dieter Sues and Ross J. Damiani in 2001 and the type species is Sauropareion anoplus. The generic name means "lizard", sauros, and "cheek", pareion from Greek in reference to the lizard-like appearance of the temporal region. The specific name comes from the Greek word anoplos, meaning "without arms or armour".

Coletta is an extinct genus of basal procolophonid parareptile from Early Triassic deposits of Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. It is known from the holotype GHG 228, a skull with fragmentary lower jaws. It was collected on the farm Brakfontein 333 in the Cradock District. It was found in the Katberg Formation of the Beaufort Group and referred to the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone. It was first named by Christopher E. Gow in 2000 and the type species is Coletta seca.

Theledectes is an extinct genus of theledectine procolophonid parareptile from middle Triassic deposits of Free State Province, South Africa.The type species, Theledectes perforatus, is based on the holotype BP/1/4585, a flattened skull. This skull was collected by the South African palaeontologist, James W. Kitching from Hugoskop in the Rouxville District and referred to subzone B of the Cynognathus Assemblage Zone of the Burgersdorp Formation, Beaufort Group. The genus was first named by Sean P. Modesto and Ross J. Damiani in 2003. However, the species was initially assigned to the genus Thelegnathus by C.E. Gow in 1977, as the species Thelegnathus perforatus.

Theledectinae is an extinct subfamily of parareptiles within the family Procolophonidae. Theledectines existed in South Africa, China and Australia during the Early-Middle Triassic period. Theledectinae was named by Juan Carlos Cisneros in 2008 to include the genus Theledectes, and the species "Eumetabolodon" dongshengensis. "E." dongshengensis represents a new genus from China. Cladistically, it is defined as "All taxa more closely related to Theledectes perforatus than to Procolophon trigoniceps Owen, 1876". In 2020, Hamley add the new genus Eomurruna from Australia to this subfamily.

Thelerpeton is an extinct genus of procolophonine procolophonid parareptile from middle Triassic deposits of Free State Province, South Africa. It is known from the holotype BP/1/4538, a nearly complete skull. It was collected by the South African palaeontologist, James W. Kitching from Hugoskop in the Rouxville District and referred to subzone B of the Cynognathus Assemblage Zone of the Burgersdorp Formation, Beaufort Group. It was first named by Sean P. Modesto and Ross J. Damiani in 2003 and the type species is Thelerpeton oppressus. It was first assigned to a species of Thelegnathus, Thelegnathus oppressus.

Anomoiodon is an extinct genus of procolophonine procolophonid parareptile from early Triassic deposits of Thuringia, Germany. It is known only from the holotype MB.R.3539B and paratype MB.R.3539A, two articulated, three-dimensionally preserved partial skeletons on one block which represent two individuals. The holotype includes nearly complete skull and lower jaw. The block was collected from the lowest layer of the Chirotherium Sandstone Member of the Solling Formation, dating to the early Olenekian faunal stage of the Early Triassic, about 249-247 million years ago. It was first named by Friedrich von Huene in 1939 and the type species is Anomoiodon liliensterni. Laura K. Säilä, who redescribed Anomoiodon in 2008, found it to be a leptopleuronine using a phylogenetic analysis. The most recent analysis, performed by Ruta et al. (2011) found it to be a procolophonine instead. However, both analyses found that it is most closely related to the Russian procolophonid Kapes.

Leptopleuroninae is an extinct subfamily of procolophonid reptiles. The oldest member of Leptopleuroninae is Phonodus dutoitorum from the Induan age of the Early Triassic. It is the only procolophonid group that survived into the Late Triassic.

Saurodektes is an extinct genus of owenettid procolophonoid parareptile known from the earliest Triassic deposits of Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. It was first named by Sean P. Modesto, Ross J. Damiani, Johann Neveling and Adam M. Yates in 2003 and the type species is Saurodectes rogersorum. The generic name Saurodectes was preoccupied by the generic name of Saurodectes vrsanskyi Rasnitsyn & Zherikhin, 2000, a fossil chewing lice known from the Early Cretaceous of Russia. Thus, an alternative generic name, Saurodektes, was proposed by Modesto et al. in 2004. The generic name means "lizard", sauros, and "biter", dektes from Greek. The specific name, rogersorum, honors Richard and Jenny Rogers, owners of the farm Barendskraal, for their hospitality, support and interest in the work of the paleontologists who recovered the holotype. Saurodektes is known solely from the holotype BP/1/6025, a partial skull and some fragmentary partial postcranial elements, housed at the Bernard Price Institute for Palaeontological Research, although the unprepared specimens BP/1/6044, BP/1/6045 and BP/1/6047 might also be referable to it. All specimens were collected on the slopes of the Manhaar Hill at Barendskraal in the Middelburg District, from the Palingkloof Member of the Balfour Formation, Beaufort Group, only 12 metres below the base of the Katberg Formation. This horizon belongs to the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone, dating to the early Induan stage of the Early Triassic period.

The Katberg Formation is a geological formation that is found in the Beaufort Group, a major geological group that forms part of the greater Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. The Katberg Formation is the lowermost geological formation of the Tarkastad Subgroup which contains the Lower to Middle Triassic-aged rocks of the Beaufort Group. Outcrops and exposures of the Katberg Formation are found east of 24 degrees on wards and north of Graaff-Reniet, Nieu Bethesda, Cradock, Fort Beaufort, Queensdown, and East London in the south, and ranges as far north as Harrismith in deposits that form a ring around the Drakensberg mountain ranges.