Ronald Lawrence Kovic is an American anti-war activist, author, and United States Marine Corps sergeant who was wounded and paralyzed in the Vietnam War. His best selling 1976 memoir Born on the Fourth of July was made into the film of the same name which starred actor Tom Cruise as Kovic, and was co-written by Kovic and directed by Oliver Stone.

The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory and the Legacy of Vietnam is a 1998 book by Vietnam veteran and sociology professor Jerry Lembcke. The book is an analysis of the widely believed narrative that American soldiers were spat upon and insulted by anti-war protesters upon returning home from the Vietnam War. The book examines the origin of the earliest stories; the popularization of the "spat-upon image" through Hollywood films and other media, and the role of print news media in perpetuating the now iconic image through which the history of the war and anti-war movement has come to be represented.

Scott Camil is an American political activist. He first gained prominence as an opponent of the Vietnam War, as a witness in the Winter Soldier Investigation and a member of Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War began in 1965 with demonstrations against the escalating role of the United States in the war. Over the next several years, these demonstrations grew into a social movement which was incorporated into the broader counterculture of the 1960s.

The Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam was a massive demonstration and teach-in across the United States against the United States involvement in the Vietnam War. It took place on October 15, 1969, followed a month later, on November 15, 1969, by a large Moratorium March in Washington, D.C.

The "Winter Soldier Investigation" was a media event sponsored by the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) from January 31, 1971, to February 2, 1971. It was intended to publicize war crimes and atrocities by the United States Armed Forces and their allies in the Vietnam War. The VVAW challenged the morality and conduct of the war by showing the direct relationship between military policies and war crimes in Vietnam. The three-day gathering of 109 veterans and 16 civilians took place in Detroit, Michigan. Discharged servicemen from each branch of the armed forces, as well as civilian contractors, medical personnel and academics, all gave testimony about war crimes they had committed or witnessed during the years 1963–1970.

Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) is an American tax-exempt non-profit organization and corporation founded in 1967 to oppose the United States policy and participation in the Vietnam War. VVAW is a national veterans' organization that campaigns for peace, justice, and the rights of all United States military veterans. It publishes a twice-yearly newsletter, The Veteran; this was earlier published more frequently as 1st Casualty (1971–1972) and then as Winter Soldier (1973–1975).

Sir! No Sir! is a 2005 documentary by Displaced Films about the anti-war movement within the ranks of the United States Armed Forces during the Vietnam War. The film was produced, directed, and written by David Zeiger. The film had a theatrical run in 80 cities throughout the U.S. and Canada in 2006, and was broadcast worldwide on Sundance Channel, Discovery Channel, BBC, ARTE France, ABC Australia, SBC Spain, ZDF Germany, YLE Finland, RT, and several others.

The nationwide student anti-war strike of 1970 was a massive outpouring of anti-Vietnam War protests that erupted in May of 1970 in response to the expansion of the war into neighboring Cambodia. The strike began on May 1 with walk-outs from college and high school classrooms on nearly 900 campuses across the United States. It increased dramatically following the shooting of students at Kent State University in Ohio by National Guardsmen on May 4. While a number violent incidents occurred during the protests, for the most part, they were peaceful.

The Fort Hood Three were three United States Army soldiers – Private First Class James Johnson, Private David A. Samas, and Private Dennis Mora – who refused to be deployed to fight in the Vietnam War on June 30, 1966. This was the first public refusal of orders to Vietnam, and one of the earliest acts of resistance to the war from within the U.S. military. Their refusal was widely publicized and became a cause célèbre within the growing antiwar movement. They filed a federal suit against Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara and Secretary of the Army Stanley Resor to prevent their shipment to Southeast Asia and were court-martialed by the Army for insubordination.

The Concerned Officers Movement (COM) was an organization of mainly junior officers formed within the U.S. military in the early 1970s. Though its principal purpose was opposition to the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, it also fought for First Amendment rights within the military. It was initiated in the Washington, D.C., area by commissioned officers who were also Vietnam Veterans, but rapidly expanded throughout all branches and many bases of the U.S. military, ultimately playing an influential role in the opposition to the Vietnam War. At least two of its chapters expanded their ranks to include enlisted personnel (non-officers), in San Diego changing the group's name to Concerned Military, and in Kodiak, Alaska, to Concerned Servicemen's Movement.

The Stop Our Ship (SOS) movement, a component of the overall civilian and GI movements against the Vietnam War, was directed towards and developed on board U.S. Navy ships, particularly aircraft carriers heading to Southeast Asia. It was concentrated on and around major U.S. Naval stations and ships on the West Coast from mid-1970 to the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, and at its height involved tens of thousands of antiwar civilians, military personnel and veterans. It was sparked by the tactical shift of U.S. combat operations in Southeast Asia from the ground to the air. As the ground war stalemated and Army grunts increasingly refused to fight or resisted the war in various other ways, the U.S. “turned increasingly to air bombardment”. By 1972 there were twice as many Seventh Fleet aircraft carriers in the Gulf of Tonkin as previously and the antiwar movement, which was at its height in the U.S. and worldwide, became a significant factor in the Navy. While no ships were actually prevented from returning to war, the campaigns, combined with the broad antiwar and rebellious sentiment of the times, stirred up substantial difficulties for the Navy, including active duty sailors refusing to sail with their ships, circulating petitions and antiwar propaganda on board, disobeying orders, and committing sabotage, as well as persistent civilian antiwar activity in support of dissident sailors. Several ship combat missions were postponed or altered and one ship was delayed by a combination of a civilian blockade and crewmen jumping overboard.

Waging Peace in Vietnam: U.S. Soldiers and Veterans Who Opposed the War is a non-fiction book edited by Ron Carver, David Cortright, and Barbara Doherty. It was published in September 2019 by New Village Press and is distributed by New York University Press. In March 2023 a Vietnamese language edition of the book was launched at the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

In the early hours of May 9, 1970, President Richard Nixon made an unplanned visit to the Lincoln Memorial where he spoke with anti-war protesters and students for almost two hours. The protesters were conducting a vigil in protest of Nixon's recent decision to expand the Vietnam War into Cambodia and the recent deaths of students in the Kent State shootings.

The court-martial of Susan Schnall, a lieutenant U.S. Navy nurse stationed at the Oakland Naval Hospital in Oakland, California, took place in early 1969 during the Vietnam War. Her political activities, which led to the military trial, may have garnered some of the most provocative news coverage during the early days of the U.S. antiwar movement against that war. In October 1968, the San Francisco Chronicle called her the “Peace Leaflet Bomber” for raining tens of thousands of antiwar leaflets from a small airplane over several San Francisco Bay Area military installations and the deck of an aircraft carrier. The day after this “bombing” run, she marched in her officer’s uniform at the front of a large antiwar demonstration, knowing it was against military regulations. While the Navy was court-martialing her for "conduct unbecoming an officer", she was publicly telling the press, "As far as I'm concerned, it's conduct unbecoming to officers to send men to die in Vietnam."

The Newsreel, most frequently called Newsreel, was an American filmmaking collective founded in New York City in late 1967. In keeping with the radical student/youth, antiwar and Black power movements of the time, the group explicitly described its purpose as using "films and other propaganda in aiding the revolutionary movement." The organization quickly established other chapters in San Francisco, Boston, Washington, DC, Atlanta, Detroit, Chicago, Los Angeles and Puerto Rico, and soon claimed "150 full time activists in its 9 regional offices." Co-founder Robert Kramer called for "films that unnerve, that shake people's assumptions…[that] explode like grenades in people’s faces, or open minds like a good can opener." Their film's production logo was a flashing graphic of The Newsreel moving in and out violently in cadence with the staccato sounds of a machine gun. A contemporary issue of Film Quarterly described it as "the cinematic equivalent of Leroi Jones's line 'I want poems that can shoot bullets.'" The films produced by Newsreel soon became regular viewing at leftwing political gatherings during the late 1960s and early 1970s; seen in "parks, church basements, on the walls of buildings, in union halls, even at Woodstock." This history has been largely ignored by film and academic historians causing the academic Nathan Rosenberger to remark: "it is curious that Newsreel only occasionally shows up in historical studies of the decade."

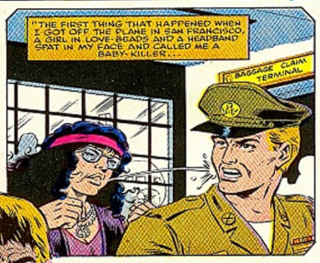

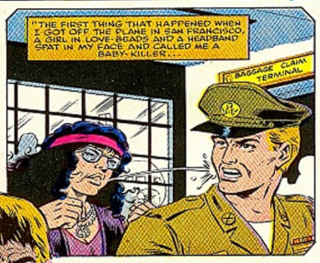

There is a persistent myth or misconception that many Vietnam War veterans were spat on and vilified by antiwar protesters during the late 1960s and early 1970s. These stories, which overwhelmingly surfaced many years after the war, usually involve an antiwar female spitting on a veteran, often yelling "baby killer". Most occur in U.S. civilian airports, usually San Francisco International, as GIs returned from the war zone in their uniforms.

Carl Douglas Rogers (1954–2016) was an American anti-war activist, writer, Sunday School teacher, and cancer patient advocate. Briefly a chaplain's assistant in Vietnam, he publicly denounced the conflict, and in 1967, he became a co-founder and vice president of protest organization Vietnam Veterans Against the War.

Barry Romo was an American antiwar activist. He joined the US military as a second lieutenant in 1967 and was initially a strong support of the Vietnam War, but within four years had become a leader of Vietnam Veterans Against the War.