Alexander Hugh Holmes Stuart was a prominent Virginia lawyer and American political figure associated with several political parties. Stuart served in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly, as a U.S. Congressman (1841-1843), and as the Secretary of the Interior. Despite opposing Virginia's secession and holding no office after finishing his term in the Virginia Senate during the American Civil War, after the war he was denied a seat in Congress. Stuart led the Committee of Nine, which attempted to reverse the changes brought by Reconstruction. He also served as rector of the University of Virginia.

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Virginia is the document that defines and limits the powers of the state government and the basic rights of the citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Like all other state constitutions, it is supreme over Virginia's laws and acts of government, though it may be superseded by the United States Constitution and U.S. federal law as per the Supremacy Clause.

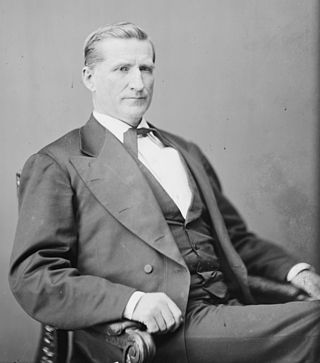

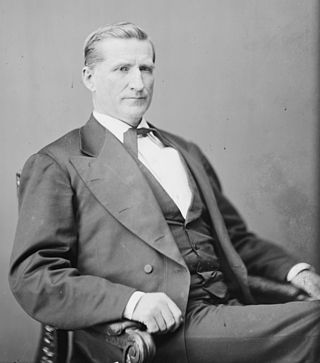

John Goode Jr. was a Virginia attorney and Democratic politician. He served in both the United States Congress and the Confederate Congress, and was a colonel in the Confederate Army. He was Solicitor General of the United States during the presidency of Grover Cleveland. He was known as "the grand old man of Virginia."

William Henry Harrison Ross was an American politician from Seaford, in Sussex County, Delaware, United States. He was a member of the Democratic Party who served as Governor of Delaware.

Wyndham Robertson was the Acting Governor of the U.S. state of Virginia from 1836 to 1837. He also twice served multiple terms in the Virginia House of Delegates, the second series representing Richmond during the American Civil War.

The Virginia Conventions have been the assemblies of delegates elected for the purpose of establishing constitutions of fundamental law for the Commonwealth of Virginia superior to General Assembly legislation. Their constitutions and subsequent amendments span four centuries across the territory of modern-day Virginia, West Virginia and Kentucky.

The Massachusetts Constitutional Convention of 1853 met from May 4 to August 2 in order to consider changes to the Massachusetts Constitution. This was the third such convention in Massachusetts history, following the original constitutional convention, in 1779–80 and the second, in 1820–21, which resulted in the adoption of the first nine amendments.

William Lucas was a nineteenth-century planter, politician and lawyer from Virginia.

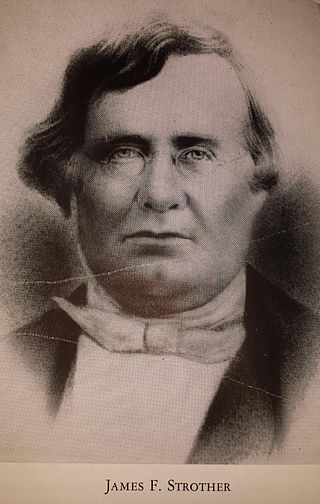

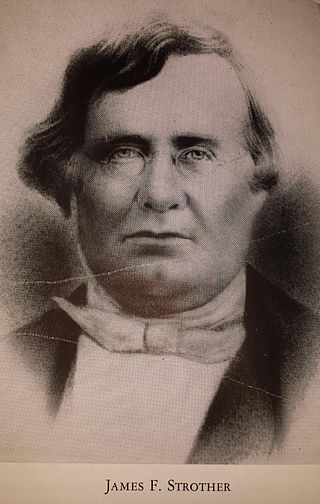

James French Strother was a nineteenth-century American politician and lawyer from a noted Virginia political family of lawyers, military officers and judges. He was the grandson of French Strother who served in the Continental Congress and both houses of the Virginia General Assembly, son of Congressman George Strother and grandfather of Congressman James F. Strother.

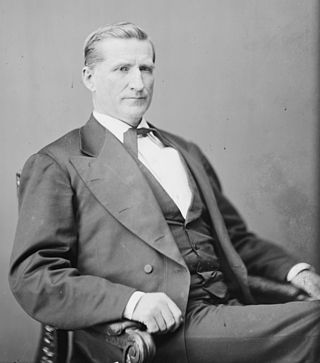

John Minor Botts was a nineteenth-century politician, planter and lawyer from Virginia. He was a prominent Unionist in Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War.

The Constitution of Indiana is the highest body of state law in the U.S. state of Indiana. It establishes the structure and function of the state and is based on the principles of federalism and Jacksonian democracy. Indiana's constitution is subordinate only to the U.S. Constitution and federal law. Prior to the enactment of Indiana's first state constitution and achievement of statehood in 1816, the Indiana Territory was governed by territorial law. The state's first constitution was created in 1816, after the U.S. Congress had agreed to grant statehood to the former Indiana Territory. The present-day document, which went into effect on November 1, 1851, is the state's second constitution. It supersedes Indiana's 1816 constitution and has had numerous amendments since its initial adoption.

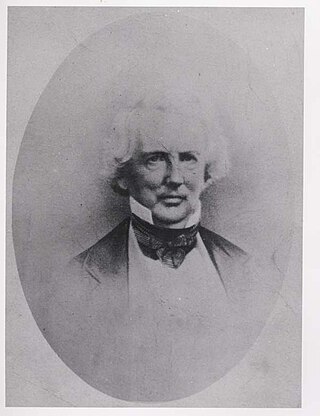

John Janney was an influential member of the Whig Party in Virginia prior to its demise, delegate to the Virginia General Assembly from Loudoun County and served as President of the Virginia Secession Convention in 1861.

John Rogers Cooke was an immigrant from Britain's Caribbean colonies who became a prominent Virginia lawyer, as well as planter, author and politician. He served a single term in the Virginia House of Delegates and became a key delegate in the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829-1830.

Oscar Minor Crutchfield was a Virginia lawyer, politician and planter who represented Spotsylvania County in the Virginia House of Delegates for many years, and in the final decade of his life served as that body's Speaker from 1852 until 1861. He presided over the House during the special session that on 19 January 1861 approved the calling of a state convention to consider Virginia's response to the secession crisis.

Charles James Faulkner was a politician, planter, and lawyer from Berkeley County, Virginia who served in both houses of the Virginia General Assembly and as a U.S. Congressman.

The Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829–1830 was a constitutional convention for the state of Virginia, held in Richmond from October 5, 1829 to January 15, 1830.

The Virginia Secession Convention of 1861 was called in Richmond to determine whether Virginia would secede from the United States, govern the state during a state of emergency, and write a new Constitution for Virginia, which was subsequently voted down in a referendum under the Confederate Government.

The Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1868, was an assembly of delegates elected by the voters to establish the fundamental law of Virginia following the American Civil War and the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. The Convention, which met from December 3, 1867 until April 17, 1868, set the stage for enfranchising freedmen, Virginia's readmission to Congress and an end to Congressional Reconstruction.

The Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1902 was an assembly of delegates elected by the voters to write the fundamental law of Virginia. The 1902 Constitution's severe restrictions of suffrage among both blacks and whites was proclaimed without submitting it to the people.

Eustace Conway was a Virginia lawyer, politician and judge.