Perry County is a county in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 28,473. Its county seat is Hazard. The county was founded in 1820. Both the county and county seat are named for Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, a naval hero in the War of 1812.

Lee County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 7,395. Its county seat is Beattyville. The county was formed in 1870 from parts of Breathitt, Estill, Owsley and Wolfe counties. The county was named for Robert E. Lee. The area of Kentucky where Lee County is located was a pro-union region of Kentucky but the legislature that created the county was controlled by former Confederates. The town of Proctor, named for the Rev. Joseph Proctor, was the first county seat. The first court was held on April 25, 1870, in the old Howerton House. The local economy at the time included coal mining, salt gathering, timber operations, and various commercial operations. It had a U.S. post office from 1843 until 1918.

Jackson County is located in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 12,955. Its county seat is McKee. The county was formed in 1858 from land given by Madison, Estill, Owsley, Clay, Laurel, and Rockcastle counties. It was named for Andrew Jackson, seventh President of the United States. Jackson County became a moist county via a "local-option" referendum in the Fall of 2019 that made the sale of alcoholic beverages in the county seat, McKee, legal.

Breathitt County is a county in the eastern Appalachian portion of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 13,718. Its county seat is Jackson. The county was formed in 1839 and was named for John Breathitt, who was Governor of Kentucky from 1832 to 1834. Breathitt County was a prohibition or dry county, until a public vote in July 2016 that allowed alcohol sales.

Bell County is a county located in the southeast part of the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 24,097. Its county seat is Pineville and its largest city is Middlesboro. The county was formed in 1867, during the Reconstruction era from parts of Knox and Harlan counties and augmented from Knox County in 1872. The county is named for Joshua Fry Bell, a US Representative. It was originally called "Josh Bell", but on January 31, 1873, the Kentucky legislature shortened the name to "Bell",

Habersham County is a county located in the northeastern part of the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 46,031. The county seat is Clarkesville. The county was created on December 15, 1818, and named for Colonel Joseph Habersham of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War.

Southside is a city located in Etowah County in the U.S. state of Alabama. It is included in the Gadsden Metropolitan Statistical Area. It incorporated in 1957. The population was 8,412 at the time of the 2010 United States Census. Located 8 to 12 miles south of downtown Gadsden, Southside is one of the fastest-growing cities in northeast Alabama. The current Mayor, elected in 2020, is Dana Snyder.

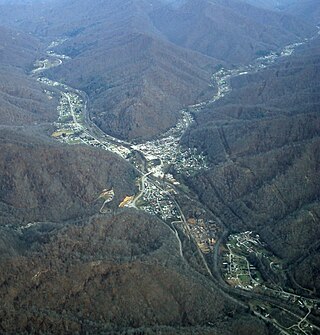

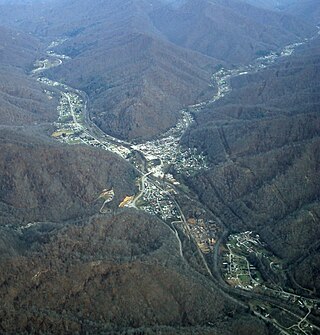

Jackson is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Breathitt County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 2,231 according to the 2010 U.S. census.

Martin is a home rule-class city in Floyd County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 634 as of the 2010 census.

Wheelwright is a home rule-class city in Floyd County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 780 at the 2010 census, down from 1,042 in 2000.

Evarts is a home rule-class city in Harlan County, Kentucky, in the United States. The post office was opened on February 9, 1855, and named for one of the area's pioneer families. The city was formally incorporated by the state assembly in 1921. The population was 962 at the 2010 census.

Harlan is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Harlan County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 1,745 at the 2010 census, down from 2,081 at the 2000 census.

Cynthiana is a home rule-class city in Harrison County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 6,402 at the 2010 census. It is the seat of its county.

McKee is a home rule-class city located in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. It is the seat and second-largest community of Jackson County, KY. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 803. The city was founded on April 1, 1882, and was named for Judge George R. McKee. In 2019, the city held a vote regarding the sale of alcohol, which passed, making the city wet.

Hindman is a home rule-class town in, and the county seat of, Knott County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 777 at the 2010 U.S. census.

Louisa is a home-rule class city located in eastern Kentucky at the merger of the Levisa and Tug Forks into the Big Sandy River, which forms part of the state's border with West Virginia. It is the seat of Lawrence County. The population was 2,467 at the 2010 census and an estimated 2,375 in 2018.

Blackey is an unincorporated community in Letcher County, Kentucky, in the United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 120. It is located near the early settlement of Indian Bottom. Blackey is thought to have been named after Blackey Brown, one of its citizens.

Fleming-Neon also known as Neon, is a home rule-class city in Letcher County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 770 at the 2010 census, down from 840 at the 2000 census.

Pine Knot is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in McCreary County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 1,380 at the 2020 census, down from 1,621 in 2010.

CoreCivic, formerly the Corrections Corporation of America (CCA), is a company that owns and manages private prisons and detention centers and operates others on a concession basis. Co-founded in 1983 in Nashville, Tennessee by Thomas W. Beasley, Robert Crants, and T. Don Hutto, it received investments from the Tennessee Valley Authority, Vanderbilt University, and Jack C. Massey, the founder of Hospital Corporation of America.