Epidemiology

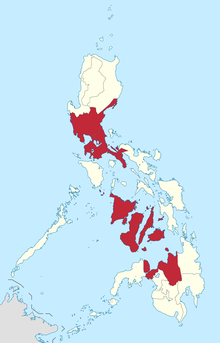

The Department of Health (DOH) of the Philippines declared a measles outbreak in Metro Manila due to a 550% increase in the number of patients from January 1 to February 6, 2019, compared to figures of the equivalent period from 2018. [1] Outbreaks were also officially declared in Central Luzon, Calabarzon, Western Visayas, Central Visayas. [2] [3] and Northern Mindanao. [4] A joint report by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and World Health Organization has stated in the report that the outbreak started much earlier in late-2017 in Mindanao. [5]

Metro Manila and Calabarzon being the most affected regions with at least a thousand cases each. [6] [7]

The DOH has recorded at 8,443 cases from January 1 to February 18, 2019, with 135 of these cases resulting to deaths. [8] On March 1, 2019, it was reported that there are at least 13,723 cases and 215 deaths recorded nationwide. [4]

By April 30, the DOH declared that the measles outbreak is already under control but remained hesitant in officially lifting the outbreak declaration. There are 31,056 cases and 415 deaths recorded from January 1 to April 13. [9]

Cause

Vaccination against measles is available for free in government hospitals and health centers but there is a lowered trust in vaccination in the country. According to an opinion poll conducted by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in 2018, 32 percent of the surveyed 1,500 Filipinos trusted vaccines. In the 2015 iteration of the poll, 93 percent of the respondents said they trusted vaccines. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III attributes the lowered trust on the government's immunization drive due to the Dengvaxia controversy. [11]

The United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) said that the outbreak is caused by "failure of the health system" saying that the distribution of vaccines down to the barangay level has not worked properly. They cited that immunization rates in the country have been declining in the past 10 to 15 years with about 74% immunized at the time of the outbreak compared to a high of 88%; 10 or 15 years ago. [1] UNICEF and the WHO has also attributed increase vaccine hesitancy in 2018 due to the Dengue vaccine controversy as a factor contributing to the outbreak. [5] Statistical data from UNICEF, however, shows that decline in Measles vaccination began as early as 2014, four years before the Dengvaxia controversy happened. [12]

As of March 1, 2019, 62 percent of all cases recorded at that time involved individuals who were not vaccinated against measles. [4]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.