The 800s decade ran from January 1, 800, to December 31, 809.

The 820s decade ran from January 1, 820, to December 31, 829.

The 840s decade ran from January 1, 840, to December 31, 849.

The 850s decade ran from January 1, 850, to December 31, 859.

The 860s decade ran from January 1, 860, to December 31, 869.

The 880s decade ran from January 1, 880, to December 31, 889.

The 710s decade ran from January 1, 710, to December 31, 719.

The 920s decade ran from January 1, 920, to December 31, 929.

Year 810 (DCCCX) was a common year starting on Tuesday of the Julian calendar.

Year 851 (DCCCLI) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar.

Year 713 (DCCXIII) was a common year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar, the 713th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 713th year of the 1st millennium, the 13th year of the 8th century, and the 4th year of the 710s decade. The denomination 713 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Year 873 (DCCCLXXIII) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar.

Year 882 (DCCCLXXXII) was a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar.

Year 888 (DCCCLXXXVIII) was a leap year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar.

Íñigo Arista was a Basque chieftain and the first king of Pamplona. He is thought to have risen to prominence after the defeat of local Frankish partisans at the Battle of Pancorbo in 816, and his rule is usually dated from shortly after the defeat of a Carolingian army in 824.

Fortún Garcés nicknamed the One-eyed, and years later the Monk, was king of Pamplona from 870/882 until 905. He appears in Arabic records as Fortoûn ibn Garsiya (فرتون بن غرسية). He was the eldest son of García Iñíguez and grandson of Íñigo Arista, the first king of Pamplona. Reigning for about thirty years, Fortún Garcés would be the last king of the Íñiguez dynasty.

García Íñiguez I, also known as García I was the second king of Pamplona from 851–2 until his death. He was the son of Íñigo Arista, the first king of Pamplona. Educated in Cordoba, he was a successful military leader who led the military campaigns of the kingdom during the last years of his father's life.

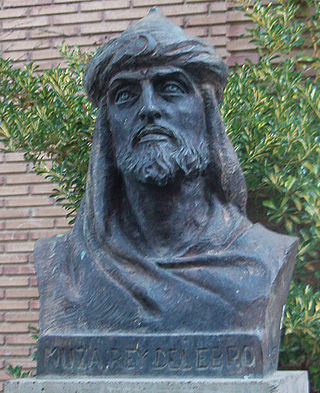

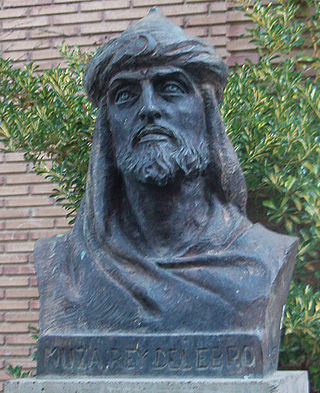

The first Battle of Albelda took place near Albelda in 851 between the Muslim forces of Musa ibn Musa, chief of the Banu Qasi and governor of Tudela on behalf of the Emirate of Córdoba, and an army of the Franks and Gascons from France, probably allies of the Christian Kingdom of Asturias, inveterate enemy of Musa. The Muslims, who were probably the aggressors, were victorious. The battle is usually connected with a campaign of Ordoño I of Asturias to suppress a Basque revolt, and may be related also to the capture of certain Frankish and Gascon leaders. In the past it has been conflated with the Battle of Monte Laturce, also near Albelda, which occurred in 859 or 860.

Musa ibn Musa al-Qasawi (Arabic: موسى بن موسى القسوي) also nicknamed the Great ; died 26 September 862) was leader of the Muwallad Banu Qasi clan and ruler of a semi-autonomous principality in the upper Ebro valley in northern Iberia in the 9th century.

The Battle of Monte Laturce, also known as the second Battle of Albelda, was a victory for the forces of Ordoño I of Asturias and his ally García Íñiguez of Pamplona. They defeated the latter's uncle and former ally, the Banu Qasi lord of Borja, Zaragoza, Terrer, and Tudela, Navarre, Musa ibn Musa al-Qasawi, a marcher baron so powerful and independent that he was called by an Andalusi chronicler "The Third King of the Spains" (Spaniae). The battle took place during the Asturian siege of a new fortress under construction by Musa at Albelda de Iregua. The fortress was taken a few days after the battle. After Monte Laturce, Musa was forced to fully submit to the Emir of Córdoba, who took advantage of Musa's weakness to remove him as wāli of the Upper March, initiating a decade-long eclipse of the Banu Qasi.