Transcription is the process of copying a segment of DNA into RNA. The segments of DNA transcribed into RNA molecules that can encode proteins are said to produce messenger RNA (mRNA). Other segments of DNA are copied into RNA molecules called non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs). mRNA comprises only 1–3% of total RNA samples. Less than 2% of the human genome can be transcribed into mRNA, while at least 80% of mammalian genomic DNA can be actively transcribed, with the majority of this 80% considered to be ncRNA.

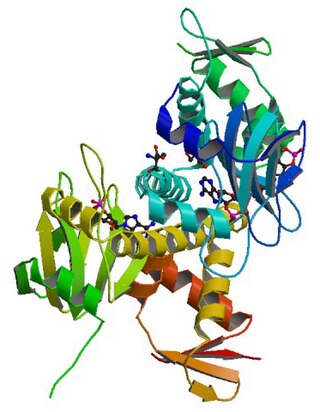

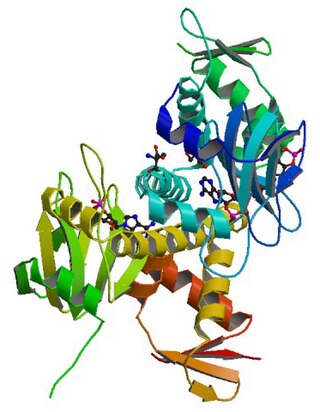

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase, or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reactions that synthesize RNA from a DNA template.

In molecular biology and genetics, transcriptional regulation is the means by which a cell regulates the conversion of DNA to RNA (transcription), thereby orchestrating gene activity. A single gene can be regulated in a range of ways, from altering the number of copies of RNA that are transcribed, to the temporal control of when the gene is transcribed. This control allows the cell or organism to respond to a variety of intra- and extracellular signals and thus mount a response. Some examples of this include producing the mRNA that encode enzymes to adapt to a change in a food source, producing the gene products involved in cell cycle specific activities, and producing the gene products responsible for cellular differentiation in multicellular eukaryotes, as studied in evolutionary developmental biology.

A sigma factor is a protein needed for initiation of transcription in bacteria. It is a bacterial transcription initiation factor that enables specific binding of RNA polymerase (RNAP) to gene promoters. It is homologous to archaeal transcription factor B and to eukaryotic factor TFIIB. The specific sigma factor used to initiate transcription of a given gene will vary, depending on the gene and on the environmental signals needed to initiate transcription of that gene. Selection of promoters by RNA polymerase is dependent on the sigma factor that associates with it. They are also found in plant chloroplasts as a part of the bacteria-like plastid-encoded polymerase (PEP).

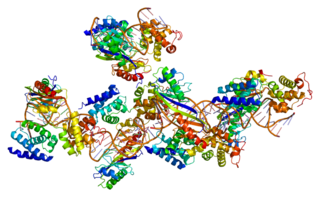

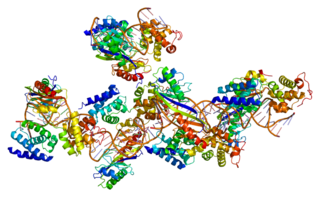

The preinitiation complex is a complex of approximately 100 proteins that is necessary for the transcription of protein-coding genes in eukaryotes and archaea. The preinitiation complex positions RNA polymerase II at gene transcription start sites, denatures the DNA, and positions the DNA in the RNA polymerase II active site for transcription.

RNA polymerase 1 is, in higher eukaryotes, the polymerase that only transcribes ribosomal RNA, a type of RNA that accounts for over 50% of the total RNA synthesized in a cell.

RNA polymerase II is a multiprotein complex that transcribes DNA into precursors of messenger RNA (mRNA) and most small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and microRNA. It is one of the three RNAP enzymes found in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. A 550 kDa complex of 12 subunits, RNAP II is the most studied type of RNA polymerase. A wide range of transcription factors are required for it to bind to upstream gene promoters and begin transcription.

General transcription factors (GTFs), also known as basal transcriptional factors, are a class of protein transcription factors that bind to specific sites (promoter) on DNA to activate transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA. GTFs, RNA polymerase, and the mediator constitute the basic transcriptional apparatus that first bind to the promoter, then start transcription. GTFs are also intimately involved in the process of gene regulation, and most are required for life.

Catabolite activator protein is a trans-acting transcriptional activator that exists as a homodimer in solution. Each subunit of CAP is composed of a ligand-binding domain at the N-terminus and a DNA-binding domain at the C-terminus. Two cAMP molecules bind dimeric CAP with negative cooperativity. Cyclic AMP functions as an allosteric effector by increasing CAP's affinity for DNA. CAP binds a DNA region upstream from the DNA binding site of RNA Polymerase. CAP activates transcription through protein-protein interactions with the α-subunit of RNA Polymerase. This protein-protein interaction is responsible for (i) catalyzing the formation of the RNAP-promoter closed complex; and (ii) isomerization of the RNAP-promoter complex to the open conformation. CAP's interaction with RNA polymerase causes bending of the DNA near the transcription start site, thus effectively catalyzing the transcription initiation process. CAP's name is derived from its ability to affect transcription of genes involved in many catabolic pathways. For example, when the amount of glucose transported into the cell is low, a cascade of events results in the increase of cytosolic cAMP levels. This increase in cAMP levels is sensed by CAP, which goes on to activate the transcription of many other catabolic genes.

In eukaryote cells, RNA polymerase III is a protein that transcribes DNA to synthesize 5S ribosomal RNA, tRNA, and other small RNAs.

T7 RNA Polymerase is an RNA polymerase from the T7 bacteriophage that catalyzes the formation of RNA from DNA in the 5'→ 3' direction.

A transcription bubble is a molecular structure formed during DNA transcription when a limited portion of the DNA double helix is unwound. The size of a transcription bubble ranges from 12 to 14 base pairs. A transcription bubble is formed when the RNA polymerase enzyme binds to a promoter and causes two DNA strands to detach. It presents a region of unpaired DNA, where a short stretch of nucleotides are exposed on each strand of the double helix.

cAMP receptor protein is a regulatory protein in bacteria. CRP protein binds cAMP, which causes a conformational change that allows CRP to bind tightly to a specific DNA site in the promoters of the genes it controls. CRP then activates transcription through direct protein–protein interactions with RNA polymerase.

Transcription factor II H (TFIIH) is an important protein complex, having roles in transcription of various protein-coding genes and DNA nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathways. TFIIH first came to light in 1989 when general transcription factor-δ or basic transcription factor 2 was characterized as an indispensable transcription factor in vitro. This factor was also isolated from yeast and finally named TFIIH in 1992.

Bacterial transcription is the process in which a segment of bacterial DNA is copied into a newly synthesized strand of messenger RNA (mRNA) with use of the enzyme RNA polymerase.

Eukaryotic transcription is the elaborate process that eukaryotic cells use to copy genetic information stored in DNA into units of transportable complementary RNA replica. Gene transcription occurs in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. Unlike prokaryotic RNA polymerase that initiates the transcription of all different types of RNA, RNA polymerase in eukaryotes comes in three variations, each translating a different type of gene. A eukaryotic cell has a nucleus that separates the processes of transcription and translation. Eukaryotic transcription occurs within the nucleus where DNA is packaged into nucleosomes and higher order chromatin structures. The complexity of the eukaryotic genome necessitates a great variety and complexity of gene expression control.

Transcription factor II B (TFIIB) is a general transcription factor that is involved in the formation of the RNA polymerase II preinitiation complex (PIC) and aids in stimulating transcription initiation. TFIIB is localised to the nucleus and provides a platform for PIC formation by binding and stabilising the DNA-TBP complex and by recruiting RNA polymerase II and other transcription factors. It is encoded by the TFIIB gene, and is homologous to archaeal transcription factor B and analogous to bacterial sigma factors.

RNA polymerase II holoenzyme is a form of eukaryotic RNA polymerase II that is recruited to the promoters of protein-coding genes in living cells. It consists of RNA polymerase II, a subset of general transcription factors, and regulatory proteins known as SRB proteins.

Richard High Ebright is an American molecular biologist. He is the Board of Governors Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Rutgers University and Laboratory Director at the Waksman Institute of Microbiology.

Archaeal transcription is the process in which a segment of archaeal DNA is copied into a newly synthesized strand of RNA using the sole Pol II-like RNA polymerase (RNAP). The process occurs in three main steps: initiation, elongation, and termination; and the end result is a strand of RNA that is complementary to a single strand of DNA. A number of transcription factors govern this process with homologs in both bacteria and eukaryotes, with the core machinery more similar to eukaryotic transcription.