An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word intron is derived from the term intragenic region, i.e., a region inside a gene. The term intron refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and the corresponding RNA sequence in RNA transcripts. The non-intron sequences that become joined by this RNA processing to form the mature RNA are called exons.

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

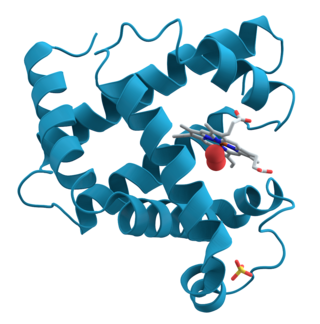

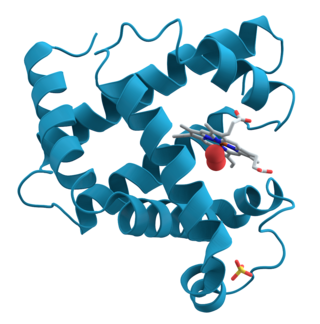

Protein biosynthesis is a core biological process, occurring inside cells, balancing the loss of cellular proteins through the production of new proteins. Proteins perform a number of critical functions as enzymes, structural proteins or hormones. Protein synthesis is a very similar process for both prokaryotes and eukaryotes but there are some distinct differences.

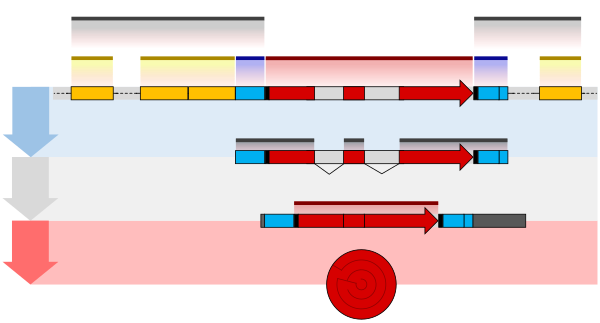

RNA splicing is a process in molecular biology where a newly-made precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) transcript is transformed into a mature messenger RNA (mRNA). It works by removing all the introns and splicing back together exons. For nuclear-encoded genes, splicing occurs in the nucleus either during or immediately after transcription. For those eukaryotic genes that contain introns, splicing is usually needed to create an mRNA molecule that can be translated into protein. For many eukaryotic introns, splicing occurs in a series of reactions which are catalyzed by the spliceosome, a complex of small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs). There exist self-splicing introns, that is, ribozymes that can catalyze their own excision from their parent RNA molecule. The process of transcription, splicing and translation is called gene expression, the central dogma of molecular biology.

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype. These products are often proteins, but in non-protein-coding genes such as transfer RNA (tRNA) and small nuclear RNA (snRNA), the product is a functional non-coding RNA. The process of gene expression is used by all known life—eukaryotes, prokaryotes, and utilized by viruses—to generate the macromolecular machinery for life.

Alternative splicing, or alternative RNA splicing, or differential splicing, is an alternative splicing process during gene expression that allows a single gene to produce different splice variants. For example, some exons of a gene may be included within or excluded from the final RNA product of the gene. This means the exons are joined in different combinations, leading to different splice variants. In the case of protein-coding genes, the proteins translated from these splice variants may contain differences in their amino acid sequence and in their biological functions.

In molecular genetics, the three prime untranslated region (3′-UTR) is the section of messenger RNA (mRNA) that immediately follows the translation termination codon. The 3′-UTR often contains regulatory regions that post-transcriptionally influence gene expression.

A cDNA library is a combination of cloned cDNA fragments inserted into a collection of host cells, which constitute some portion of the transcriptome of the organism and are stored as a "library". cDNA is produced from fully transcribed mRNA found in the nucleus and therefore contains only the expressed genes of an organism. Similarly, tissue-specific cDNA libraries can be produced. In eukaryotic cells the mature mRNA is already spliced, hence the cDNA produced lacks introns and can be readily expressed in a bacterial cell. While information in cDNA libraries is a powerful and useful tool since gene products are easily identified, the libraries lack information about enhancers, introns, and other regulatory elements found in a genomic DNA library.

Polyadenylation is the addition of a poly(A) tail to an RNA transcript, typically a messenger RNA (mRNA). The poly(A) tail consists of multiple adenosine monophosphates; in other words, it is a stretch of RNA that has only adenine bases. In eukaryotes, polyadenylation is part of the process that produces mature mRNA for translation. In many bacteria, the poly(A) tail promotes degradation of the mRNA. It, therefore, forms part of the larger process of gene expression.

In molecular biology, the five-prime cap is a specially altered nucleotide on the 5′ end of some primary transcripts such as precursor messenger RNA. This process, known as mRNA capping, is highly regulated and vital in the creation of stable and mature messenger RNA able to undergo translation during protein synthesis. Mitochondrial mRNA and chloroplastic mRNA are not capped.

A primary transcript is the single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) product synthesized by transcription of DNA, and processed to yield various mature RNA products such as mRNAs, tRNAs, and rRNAs. The primary transcripts designated to be mRNAs are modified in preparation for translation. For example, a precursor mRNA (pre-mRNA) is a type of primary transcript that becomes a messenger RNA (mRNA) after processing.

Mature messenger RNA, often abbreviated as mature mRNA is a eukaryotic RNA transcript that has been spliced and processed and is ready for translation in the course of protein synthesis. Unlike the eukaryotic RNA immediately after transcription known as precursor messenger RNA, mature mRNA consists exclusively of exons and has all introns removed.

Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) is a class of small RNA molecules that are found within the splicing speckles and Cajal bodies of the cell nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The length of an average snRNA is approximately 150 nucleotides. They are transcribed by either RNA polymerase II or RNA polymerase III. Their primary function is in the processing of pre-messenger RNA (hnRNA) in the nucleus. They have also been shown to aid in the regulation of transcription factors or RNA polymerase II, and maintaining the telomeres.

Eukaryotic chromosome fine structure refers to the structure of sequences for eukaryotic chromosomes. Some fine sequences are included in more than one class, so the classification listed is not intended to be completely separate.

Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF) is involved in the cleavage of the 3' signaling region from a newly synthesized pre-messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) molecule in the process of gene transcription. In eukaryotes, messenger RNA precursors (pre-mRNA) are transcribed in the nucleus from DNA by the enzyme, RNA polymerase II. The pre-mRNA must undergo post-transcriptional modifications, forming mature RNA (mRNA), before they can be transported into the cytoplasm for translation into proteins. The post-transcriptional modifications are: the addition of a 5' m7G cap, splicing of intronic sequences, and 3' cleavage and polyadenylation.

Cleavage factors are two closely associated protein complexes involved in the cleavage of the 3' untranslated region of a newly synthesized pre-messenger RNA (mRNA) molecule in the process of gene transcription. The cleavage is the first step in adding a polyadenine tail to the pre-mRNA, which is one of the necessary post-transcriptional modifications necessary for producing a mature mRNA molecule.

Eukaryotic transcription is the elaborate process that eukaryotic cells use to copy genetic information stored in DNA into units of transportable complementary RNA replica. Gene transcription occurs in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. Unlike prokaryotic RNA polymerase that initiates the transcription of all different types of RNA, RNA polymerase in eukaryotes comes in three variations, each translating a different type of gene. A eukaryotic cell has a nucleus that separates the processes of transcription and translation. Eukaryotic transcription occurs within the nucleus where DNA is packaged into nucleosomes and higher order chromatin structures. The complexity of the eukaryotic genome necessitates a great variety and complexity of gene expression control.

Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor subunit 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CPSF1 gene.

mRNA surveillance mechanisms are pathways utilized by organisms to ensure fidelity and quality of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules. There are a number of surveillance mechanisms present within cells. These mechanisms function at various steps of the mRNA biogenesis pathway to detect and degrade transcripts that have not properly been processed.

Numerous key discoveries in biology have emerged from studies of RNA, including seminal work in the fields of biochemistry, genetics, microbiology, molecular biology, molecular evolution, and structural biology. As of 2010, 30 scientists have been awarded Nobel Prizes for experimental work that includes studies of RNA. Specific discoveries of high biological significance are discussed in this article.