The subphylum Chelicerata constitutes one of the major subdivisions of the phylum Arthropoda. Chelicerates include the sea spiders, horseshoe crabs, and arachnids, as well as a number of extinct lineages, such as the eurypterids and chasmataspidids.

Arachnids are arthropods in the class Arachnida of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaroons.

Centipedes are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda of the subphylum Myriapoda, an arthropod group which includes millipedes and other multi-legged animals. Centipedes are elongated segmented (metameric) creatures with one pair of legs per body segment. All centipedes are venomous and can inflict painful stings, injecting their venom through pincer-like appendages known as forcipules or toxicognaths, which are actually modified legs instead of fangs. Despite the name, no species of centipede has exactly 100 legs; the number of pairs of legs is an odd number that ranges from 15 pairs to 191 pairs.

Pseudoscorpions, also known as false scorpions or book scorpions, are small, scorpion-like arachnids belonging to the order Pseudoscorpiones, also known as Pseudoscorpionida or Chelonethida.

The family Dipluridae, known as curtain-web spiders are a group of spiders in the infraorder Mygalomorphae, that have two pairs of booklungs, and chelicerae (fangs) that move up and down in a stabbing motion. A number of genera, including that of the Sydney funnel-web spider (Atrax), used to be classified in this family but have now been moved to Atracidae.

The Mesothelae are a suborder of spiders. As of April 2024, two extant families were accepted by the World Spider Catalog, Liphistiidae and Heptathelidae. Alternatively, the Heptathelidae can be treated as a subfamily of a more broadly circumscribed Liphistiidae. There are also a number of extinct families.

The spider family Liphistiidae was first recognized by Tamerlan Thorell in 1869. When narrowly circumscribed, it comprises a single genus Liphistius, native to Southeast Asia; as of April 2024, this was the circumscription accepted by the World Spider Catalog. The family contains the most basal living spiders, belonging to the suborder Mesothelae. The family has also been circumscribed more broadly to include the family Heptathelidae as a subfamily, Heptathelinae, with the narrowly circumscribed Liphistiidae becoming the subfamily Liphistiinae.

Solifugae is an order of arachnids known variously as solifuges, sun spiders, camel spiders, and wind scorpions. The order includes more than 1,000 described species in about 147 genera. Despite the common names, they are neither true scorpions nor true spiders. Because of this, it is less ambiguous to call them "solifuges". Most species of solifuge live in dry climates and feed opportunistically on ground-dwelling arthropods and other small animals. The largest species grow to a length of 12–15 cm (5–6 in), including legs. A number of urban legends exaggerate the size and speed of solifuges, and their potential danger to humans, which is negligible.

The order Trigonotarbida is a group of extinct arachnids whose fossil record extends from the late Silurian to the early Permian. These animals are known from several localities in Europe and North America, as well as a single record from Argentina. Trigonotarbids can be envisaged as spider-like arachnids, but without silk-producing spinnerets. They ranged in size from a few millimetres to a few centimetres in body length and had segmented abdomens (opisthosoma), with the dorsal exoskeleton (tergites) across the backs of the animals' abdomens, which were characteristically divided into three or five separate plates. Probably living as predators on other arthropods, some later trigonotarbid species were quite heavily armoured and protected themselves with spines and tubercles. About seventy species are currently known, with most fossils originating from the Carboniferous coal measures.

Tetrapulmonata is a non-ranked supra-ordinal clade of arachnids. It is composed of the extant orders Uropygi, Schizomida, Amblypygi and Araneae (spiders). It is the only supra-ordinal group of arachnids that is strongly supported in molecular phylogenetic studies. Two extinct orders are also placed in this clade, Haptopoda and Uraraneida. In 2016, a newly described fossil arachnid, Idmonarachne, was also included in the Tetrapulmonata; as of March 2016 it has not been assigned to an order.

Spiders have been evolving for at least 380 million years. The group's origins lie within an arachnid sub-group defined by the presence of book lungs ; the arachnids as a whole evolved from aquatic chelicerate ancestors. More than 45,000 extant species have been described, organised taxonomically in 3,958 genera and 114 families. There may be more than 120,000 species. Fossil diversity rates make up a larger proportion than extant diversity would suggest with 1,593 arachnid species described out of 1,952 recognized chelicerates. Both extant and fossil species are described annually by researchers in the field. Major developments in spider evolution include the development of spinnerets and silk secretion.

The anatomy of spiders includes many characteristics shared with other arachnids. These characteristics include bodies divided into two tagmata, eight jointed legs, no wings or antennae, the presence of chelicerae and pedipalps, simple eyes, and an exoskeleton, which is periodically shed.

Megarachne is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Megarachne have been discovered in deposits of Late Carboniferous age, from the Gzhelian stage, in the Bajo de Véliz Formation of San Luis, Argentina. The fossils of the single and type species M. servinei have been recovered from deposits that had once been a freshwater environment. The generic name, composed of the Ancient Greek μέγας (megas) meaning "great" and Ancient Greek ἀράχνη (arachne) meaning "spider", translates to "great spider"; because the fossil was misidentified as a large, prehistoric spider.

Spiders are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species diversity among all orders of organisms. Spiders are found worldwide on every continent except Antarctica, and have become established in nearly every land habitat. As of September 2024, 52,309 spider species in 134 families have been recorded by taxonomists. However, there has been debate among scientists about how families should be classified, with over 20 different classifications proposed since 1900.

The Panther Mountain Formation is a geologic formation in New York. It preserves fossils dating back to the Devonian period. It is located in the counties of Albany, Madison, Oneida, Otsego, and Schoharie. It is well known for its fossil arthropods preserved as flattened cuticles, including Attercopus and Dracochela.

Rosamygale is a genus of extinct Triassic spiders, with a single described species, Rosamygale grauvogeli. It is the oldest known member of the Mygalomorphae, one of the three main divisions of spiders, which includes well known forms such as tarantulas and Australian funnel-web spiders. It was described by Selden and Gall in 1992, from specimens found in the Middle Triassic aged Gres a Meules and Grès à Voltzia geological formations in France. It is also considered to be the oldest known member of the Avicularioidea, one of the two main divisions of Mygalomorphae.

Uraraneida is an extinct order of Paleozoic arachnids related to modern spiders. Two genera of fossils have been definitively placed in this order: Attercopus from the Devonian of United States and Permarachne from the Permian of Russia. Like spiders, they are known to have produced silk, but lack the characteristic spinnerets of modern spiders, and retain elongate telsons.

Idmonarachne is an extinct genus of arachnids, containing one species, Idmonarachne brasieri. It is related to uraraneids and spiders.

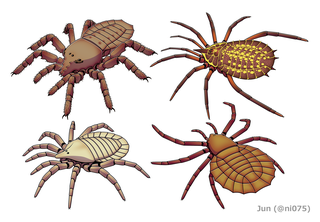

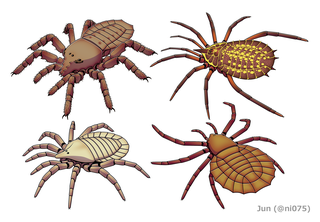

Chimerarachne is a genus of extinct arachnids, containing five species. Fossils of Chimerarachne were discovered in Burmese amber from Myanmar which dates to the mid-Cretaceous, about 100 million years ago. It is thought to be closely related to spiders, but outside any living spider clade. The earliest spider fossils are from the Carboniferous, requiring at least a 170 myr ghost lineage with no fossil record. The size of the animal is quite small, being only 2.5 millimetres (0.098 in) in body length, with the tail being about 3 millimetres (0.12 in) in length. These fossils resemble spiders in having two of their key defining features: spinnerets for spinning silk, and a modified male organ on the pedipalp for transferring sperm. At the same time they retain a whip-like tail, rather like that of a whip scorpion and uraraneids. Chimerarachne is not ancestral to spiders, being much younger than the oldest spiders which are known from the Carboniferous, but it appears to be a late survivor of an extinct group which was probably very close to the origins of spiders. It suggests that there used to be spider-like animals with tails which lived alongside true spiders for at least 200 million years.

Permarachne is an extinct genus of arachnids containing the single species Permarachne novokshonovi from the Permian (Kungurian) of Russia, found in the Koshelevka Formation near the town of Suksun in Perm Krai. It is closely related to modern spiders but unlike them, it has a long thin tail, similar to its relative Attercopus, it is known from the mostly complete holotype PIN 4909/12. It is about 1 cm in size. It initially was thought to be a spider, but is now thought to form a clade with at least its close relative Attercopus, forming the grouping Uraraneida.