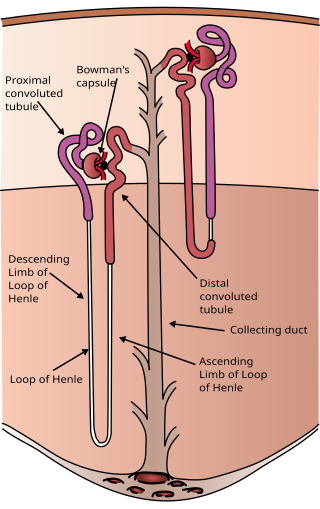

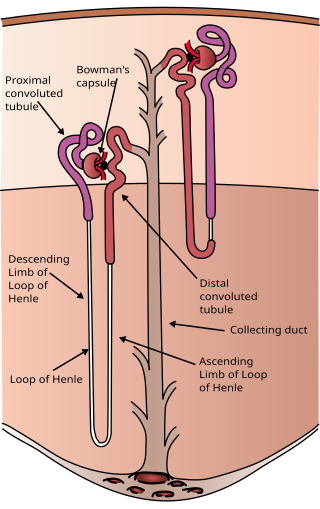

The nephron is the minute or microscopic structural and functional unit of the kidney. It is composed of a renal corpuscle and a renal tubule. The renal corpuscle consists of a tuft of capillaries called a glomerulus and a cup-shaped structure called Bowman's capsule. The renal tubule extends from the capsule. The capsule and tubule are connected and are composed of epithelial cells with a lumen. A healthy adult has 1 to 1.5 million nephrons in each kidney. Blood is filtered as it passes through three layers: the endothelial cells of the capillary wall, its basement membrane, and between the podocyte foot processes of the lining of the capsule. The tubule has adjacent peritubular capillaries that run between the descending and ascending portions of the tubule. As the fluid from the capsule flows down into the tubule, it is processed by the epithelial cells lining the tubule: water is reabsorbed and substances are exchanged ; first with the interstitial fluid outside the tubules, and then into the plasma in the adjacent peritubular capillaries through the endothelial cells lining that capillary. This process regulates the volume of body fluid as well as levels of many body substances. At the end of the tubule, the remaining fluid—urine—exits: it is composed of water, metabolic waste, and toxins.

Renin, also known as an angiotensinogenase, is an aspartic protease protein and enzyme secreted by the kidneys that participates in the body's renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS)—also known as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis—that increases the volume of extracellular fluid and causes arterial vasoconstriction. Thus, it increases the body's mean arterial blood pressure.

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS), or renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), is a hormone system that regulates blood pressure, fluid, and electrolyte balance, and systemic vascular resistance.

Angiotensin is a peptide hormone that causes vasoconstriction and an increase in blood pressure. It is part of the renin–angiotensin system, which regulates blood pressure. Angiotensin also stimulates the release of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex to promote sodium retention by the kidneys.

Smoothmuscle is one of the three major types of vertebrate muscle tissue, the others being skeletal and cardiac muscle. It can also be found in invertebrates and is controlled by the autonomic nervous system. It is non-striated, so-called because it has no sarcomeres and therefore no striations. It can be divided into two subgroups, single-unit and multi-unit smooth muscle. Within single-unit muscle, the whole bundle or sheet of smooth muscle cells contracts as a syncytium.

Cardiac muscle is one of three types of vertebrate muscle tissues, the others being skeletal muscle and smooth muscle. It is an involuntary, striated muscle that constitutes the main tissue of the wall of the heart. The cardiac muscle (myocardium) forms a thick middle layer between the outer layer of the heart wall and the inner layer, with blood supplied via the coronary circulation. It is composed of individual cardiac muscle cells joined by intercalated discs, and encased by collagen fibers and other substances that form the extracellular matrix.

The juxtaglomerular apparatus is a structure in the kidney that regulates the function of each nephron, the functional units of the kidney. The juxtaglomerular apparatus is named because it is next to (juxta-) the glomerulus.

Vasodilation, also known as vasorelaxation, is the widening of blood vessels. It results from relaxation of smooth muscle cells within the vessel walls, in particular in the large veins, large arteries, and smaller arterioles. Blood vessel walls are composed of endothelial tissue and a basal membrane lining the lumen of the vessel, concentric smooth muscle layers on top of endothelial tissue, and an adventitia over the smooth muscle layers. Relaxation of the smooth muscle layer allows the blood vessel to dilate, as it is held in a semi-constricted state by sympathetic nervous system activity. Vasodilation is the opposite of vasoconstriction, which is the narrowing of blood vessels.

Thirst is the craving for potable fluids, resulting in the basic instinct of animals to drink. It is an essential mechanism involved in fluid balance. It arises from a lack of fluids or an increase in the concentration of certain osmolites, such as sodium. If the water volume of the body falls below a certain threshold or the osmolite concentration becomes too high, structures in the brain detect changes in blood constituents and signal thirst.

In the kidney, the macula densa is an area of closely packed specialized cells lining the wall of the distal tubule where it touches the glomerulus. Specifically, the macula densa is found in the terminal portion of the distal straight tubule, after which the distal convoluted tubule begins.

The angiotensin II receptors, (ATR1) and (ATR2), are a class of G protein-coupled receptors with angiotensin II as their ligands. They are important in the renin–angiotensin system: they are responsible for the signal transduction of the vasoconstricting stimulus of the main effector hormone, angiotensin II.

Cerebral circulation is the movement of blood through a network of cerebral arteries and veins supplying the brain. The rate of cerebral blood flow in an adult human is typically 750 milliliters per minute, or about 15% of cardiac output. Arteries deliver oxygenated blood, glucose and other nutrients to the brain. Veins carry "used or spent" blood back to the heart, to remove carbon dioxide, lactic acid, and other metabolic products. The neurovascular unit regulates cerebral blood flow so that activated neurons can be supplied with energy in the right amount and at the right time. Because the brain would quickly suffer damage from any stoppage in blood supply, the cerebral circulatory system has safeguards including autoregulation of the blood vessels. The failure of these safeguards may result in a stroke. The volume of blood in circulation is called the cerebral blood flow. Sudden intense accelerations change the gravitational forces perceived by bodies and can severely impair cerebral circulation and normal functions to the point of becoming serious life-threatening conditions.

An osmoreceptor is a sensory receptor primarily found in the hypothalamus of most homeothermic organisms that detects changes in osmotic pressure. Osmoreceptors can be found in several structures, including two of the circumventricular organs – the vascular organ of the lamina terminalis, and the subfornical organ. They contribute to osmoregulation, controlling fluid balance in the body. Osmoreceptors are also found in the kidneys where they also modulate osmolality.

Juxtaglomerular cells, also known as juxtaglomerular granular cells are cells in the kidney that synthesize, store, and secrete the enzyme renin. They are specialized smooth muscle cells mainly in the walls of the afferent arterioles that deliver blood to the glomerulus. In synthesizing renin, they play a critical role in the renin–angiotensin system and thus in autoregulation of the kidney.

Myocardial contractility represents the innate ability of the heart muscle (cardiac muscle or myocardium) to contract. It is the maximum attainable value for the force of contraction of a given heart. The ability to produce changes in force during contraction result from incremental degrees of binding between different types of tissue, that is, between filaments of myosin (thick) and actin (thin) tissue. The degree of binding depends upon the concentration of calcium ions in the cell. Within an in vivo intact heart, the action/response of the sympathetic nervous system is driven by precisely timed releases of a catecholamine, which is a process that determines the concentration of calcium ions in the cytosol of cardiac muscle cells. The factors causing an increase in contractility work by causing an increase in intracellular calcium ions (Ca++) during contraction.

The afferent arterioles are a group of blood vessels that supply the nephrons in many excretory systems. They play an important role in the regulation of blood pressure as a part of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism.

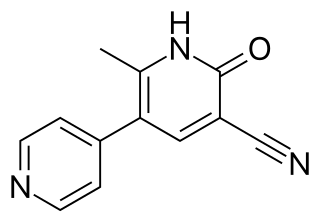

Milrinone, sold under the brand name Primacor, is a pulmonary vasodilator used in patients who have heart failure. It is a phosphodiesterase 3 inhibitor that works to increase the heart's contractility and decrease pulmonary vascular resistance. Milrinone also works to vasodilate which helps alleviate increased pressures (afterload) on the heart, thus improving its pumping action. While it has been used in people with heart failure for many years, studies suggest that milrinone may exhibit some negative side effects that have caused some debate about its use clinically.

In the physiology of the kidney, tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF) is a feedback system inside the kidneys. Within each nephron, information from the renal tubules is signaled to the glomerulus. Tubuloglomerular feedback is one of several mechanisms the kidney uses to regulate glomerular filtration rate (GFR). It involves the concept of purinergic signaling, in which an increased distal tubular sodium chloride concentration causes a basolateral release of adenosine from the macula densa cells. This initiates a cascade of events that ultimately brings GFR to an appropriate level.

Extraglomerular mesangial cells are light-staining pericytes in the kidney found outside the glomerulus, near the vascular pole. They resemble smooth muscle cells and play a role in renal autoregulation of blood flow to the kidney and regulation of systemic blood pressure through the renin–angiotensin system. Extraglomerular mesangial cells are part of the juxtaglomerular apparatus, along with the macula densa cells of the distal convoluted tubule and the juxtaglomerular cells of the afferent arteriole.

The Anrep effect describes the rapid increase in myocardial contractility in response to the sudden rise in afterload, the pressure the heart must work against to eject blood. This adaptive mechanism allows the heart to sustain stroke volume and cardiac output despite increased resistance. It operates through homeometric autoregulation, meaning that contractility adjustments occur independently of preload or heart rate.