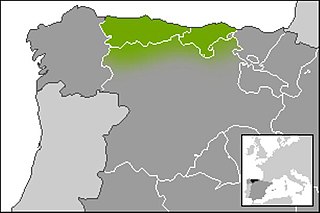

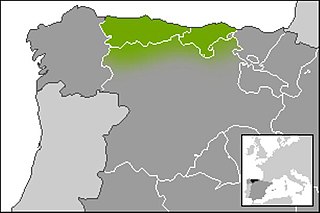

Cantabria is an autonomous community and province in northern Spain with Santander as its capital city. It is called a comunidad histórica, a historic community, in its current Statute of Autonomy. It is bordered on the east by the Basque autonomous community, on the south by Castile and León, on the west by the Principality of Asturias, and on the north by the Cantabrian Sea, which forms part of the Bay of Biscay.

Esus, Esos, Hesus, or Aisus was a Celtic god who was worshipped primarily in ancient Gaul and Britain. He is known from two monumental statues and a line in Lucan's Bellum civile.

Lusitanian mythology is the mythology of the Lusitanians, an Indo-European speaking people of western Iberia, in what was then known as Lusitania. In present times, the territory comprises the central part of Portugal and small parts of Extremadura and Salamanca.

The Lusitanians were an Indo-European-speaking people living in the far west of the Iberian Peninsula, in present-day central Portugal and Extremadura and Castilla y Leon of Spain. After its conquest by the Romans, the land was subsequently incorporated as a Roman province named after them (Lusitania).

The mythologies in present-day France encompass the mythology of the Gauls, Franks, Normans, Bretons, and other peoples living in France, those ancient stories about divine or heroic beings that these particular cultures believed to be true and that often use supernatural events or characters to explain the nature of the universe and humanity. French myth has been primarily influenced by the myths and legends of the Gauls and the Bretons as they migrated to the French region from modern day England and Ireland. Other smaller influences on the development of French mythology came from the Franks.

The Astures or Asturs, also named Astyrs, were the Hispano-Celtic inhabitants of the northwest area of Hispania that now comprises almost the entire modern autonomous community of the Principality of Asturias, the modern province of León, and the northern part of the modern province of Zamora, and eastern Trás os Montes in Portugal. They were a horse-riding highland cattle-raising people who lived in circular huts of stone drywall construction. The Albiones were a major tribe from western Asturias. Isidore of Seville gave an etymology as coming from a river Astura, identified by David Magie as the Órbigo River in the plain of León, and by others as the modern Esla River.

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe. Because there are no extant native records of their beliefs, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts, and literature from the early Christian period. Celtic paganism was one of a larger group of polytheistic Indo-European religions of Iron Age Europe.

The Cantabri or Ancient Cantabrians were a pre-Roman people and large tribal federation that lived in the northern coastal region of ancient Iberia in the second half of the first millennium BC. These peoples and their territories were incorporated into the Roman Province of Hispania Tarraconensis in 19 BC, following the Cantabrian Wars.

The Cantabrian Wars, sometimes also referred to as the Cantabrian and Asturian Wars, were the final stage of the two-century long Roman conquest of Hispania, in what today are the provinces of Cantabria, Asturias and León in northwestern Spain.

The Cantabrian labarum is a modern interpretation of the ancient military standard known by the Romans as Cantabrum. It consists of a purple cloth on which there is what would be called in heraldry a "saltire voided" made up of curved lines, with knobs at the end of each line.

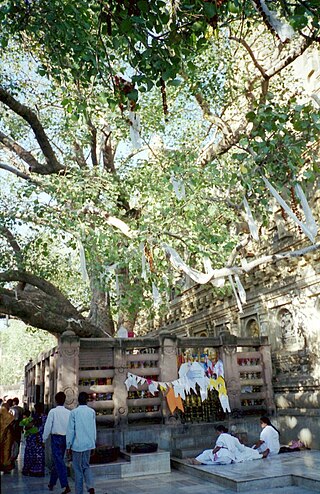

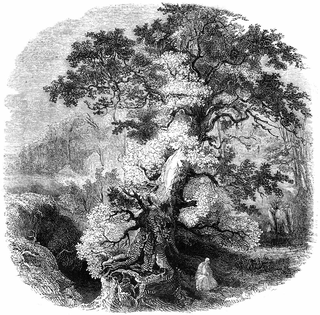

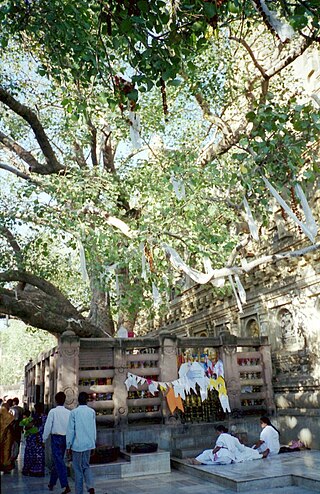

Trees are significant in many of the world's mythologies, and have been given deep and sacred meanings throughout the ages. Human beings, observing the growth and death of trees, and the annual death and revival of their foliage, have often seen them as powerful symbols of growth, death and rebirth. Evergreen trees, which largely stay green throughout these cycles, are sometimes considered symbols of the eternal, immortality or fertility. The image of the Tree of life or world tree occurs in many mythologies.

Moccus or Moccos is a Celtic god who is attested in one 2nd or 3rd century AD inscription from Langres, in which he is identified with the Roman god Mercury. Moccus has been connected, on etymological grounds, with pigs and boars. The boar was a potent symbol, of the hunt and of war, but also of prosperity.

In ancient Roman religion and mythology, Mars is the god of war and also an agricultural guardian, a combination characteristic of early Rome. He is the son of Jupiter and Juno, and was pre-eminent among the Roman army's military gods. Most of his festivals were held in March, the month named for him, and in October, the months which traditionally began and ended the season for both military campaigning and farming.

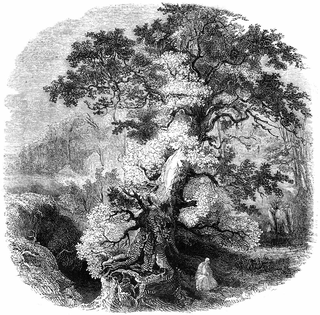

Many types of trees found in the Celtic nations are considered to be sacred, whether as symbols, or due to medicinal properties, or because they are seen as the abode of particular nature spirits. Historically and in folklore, the respect given to trees varies in different parts of the Celtic world. On the Isle of Man, the phrase 'fairy tree' often refers to the elder tree. The medieval Welsh poem Cad Goddeu is believed to contain Celtic tree lore, possibly relating to the crann ogham, the branch of the ogham alphabet where tree names are used as mnemonic devices.

According to classical sources, the ancient Celts were animists. They honoured the forces of nature, saw the world as inhabited by many spirits, and saw the Divine manifesting in aspects of the natural world.

The gods and goddesses of the pre-Christian Celtic peoples are known from a variety of sources, including ancient places of worship, statues, engravings, cult objects, and place or personal names. The ancient Celts appear to have had a pantheon of deities comparable to others in Indo-European religion, each linked to aspects of life and the natural world. Epona was an exception and retained without association with any Roman deity. By a process of syncretism, after the Roman conquest of Celtic areas, most of these became associated with their Roman equivalents, and their worship continued until Christianization. Pre-Roman Celtic art produced few images of deities, and these are hard to identify, lacking inscriptions, but in the post-conquest period many more images were made, some with inscriptions naming the deity. Most of the specific information we have therefore comes from Latin writers and the archaeology of the post-conquest period. More tentatively, links can be made between ancient Celtic deities and figures in early medieval Irish and Welsh literature, although all these works were produced well after Christianization.

The Ojáncanu is a cyclops found in Cantabrian mythology, and is an embodiment of cruelty and brutality. It appears as a 10 to 20 foot tall giant with superhuman strength, with hands and feet that contain ten digits each, and two rows of teeth. With a very wild and beast-like temperament, it sports a long mane of red hair, and just as much facial hair, with both nearly reaching to the ground. Apparently the easiest way of killing an Ojancanu is to pull the single white hair found in its mess of a beard. The females are virtually the same, though without the presence of a beard. However, the females have long drooping breasts that like their male counterpart's hair, reach the ground. In order to run, they must carry their breasts behind their shoulders. The strangest thing about these peculiar cyclopean species is their reproduction process. Instead of mating, when an old Ojancanu dies, the others distribute the insides and bury the corpse under an oak or yew tree. He is constantly doing evil deeds such as pulling up rocks, destroying huts and trees, and blocking water sources. He fights Cantabrian brown bears and Tudanca bulls, and always wins. He only fears the Anjanas, the good Cantabrian fairies.

Celtic mythology is the body of myths belonging to the Celtic peoples. Like other Iron Age Europeans, Celtic peoples followed a polytheistic religion, having many gods and goddesses. The mythologies of continental Celtic peoples, such as the Gauls and Celtiberians, did not survive their conquest by the Roman Empire, the loss of their Celtic languages and their subsequent conversion to Christianity. Only remnants are found in Greco-Roman sources and archaeology. Most surviving Celtic mythology belongs to the Insular Celtic peoples. They preserved some of their myths in oral lore, which were eventually written down by Christian scribes in the Middle Ages. Irish mythology has the largest written body of myths, followed by Welsh mythology.

The Anjana are one of the best-known fairies of Cantabrian mythology. These female fairy creatures foil the cruel and ruthless Ojáncanu. In most stories, they are the good fairies of Cantabria, generous and protective of all people. Their depiction in the Cantabrian mythology is reminiscent of the lamias in ancient Greek mythology, as well as the xanas in Asturias, the janas in León, and the lamias in Basque Country, the latter without the zoomorphic appearance.

The Caballucos del Diablu is a myth from the Cantabrian mythology, a region of northern Spain.