This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page . (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

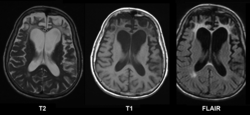

Cerebral atrophy is a common feature of many of the diseases that affect the brain. [1] Atrophy of any tissue means a decrement in the size of the cell, which can be due to progressive loss of cytoplasmic proteins. In brain tissue, atrophy describes a loss of neurons and the connections between them. Brain atrophy can be classified into two main categories: generalized and focal atrophy. [2] Generalized atrophy occurs across the entire brain whereas focal atrophy affects cells in a specific location. [2] If the cerebral hemispheres (the two lobes of the brain that form the cerebrum) are affected, conscious thought and voluntary processes may be impaired.

Contents

- Causes

- Injury

- Diseases and disorders

- Infections

- Drug-induced

- Diagnosis

- Neurofilament light chain

- Measures

- Difference from hydrocephalus

- Treatment

- Reversibility of cerebral atrophy

- See also

- References

Some degree of cerebral shrinkage occurs naturally with the dynamic process of aging. [3] Structural changes continue during adulthood as brain shrinkage commences after the age of 35, at a rate of 0.2% per year. [4] The rate of decline is accelerated when individuals reach 70 years old. [5] By the age of 90, the human brain will have experienced a 15% loss of its initial peak weight. [6] Besides brain atrophy, aging has also been associated with cerebral microbleeds. [3]