A heat engine is a system that converts heat to usable energy, particularly mechanical energy, which can then be used to do mechanical work. While originally conceived in the context of mechanical energy, the concept of the heat engine has been applied to various other kinds of energy, particularly electrical, since at least the late 19th century. The heat engine does this by bringing a working substance from a higher state temperature to a lower state temperature. A heat source generates thermal energy that brings the working substance to the higher temperature state. The working substance generates work in the working body of the engine while transferring heat to the colder sink until it reaches a lower temperature state. During this process some of the thermal energy is converted into work by exploiting the properties of the working substance. The working substance can be any system with a non-zero heat capacity, but it usually is a gas or liquid. During this process, some heat is normally lost to the surroundings and is not converted to work. Also, some energy is unusable because of friction and drag.

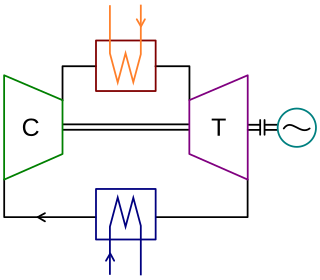

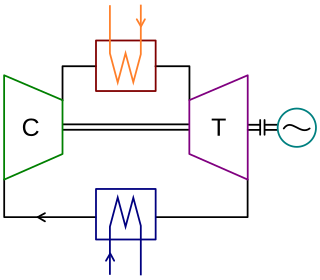

The Brayton cycle, also known as the Joule cycle, is a thermodynamic cycle that describes the operation of certain heat engines that have air or some other gas as their working fluid. It is characterized by isentropic compression and expansion, and isobaric heat addition and rejection, though practical engines have adiabatic rather than isentropic steps.

A combined cycle power plant is an assembly of heat engines that work in tandem from the same source of heat, converting it into mechanical energy. On land, when used to make electricity the most common type is called a combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) plant, which is a kind of gas-fired power plant. The same principle is also used for marine propulsion, where it is called a combined gas and steam (COGAS) plant. Combining two or more thermodynamic cycles improves overall efficiency, which reduces fuel costs.

The Rankine cycle is an idealized thermodynamic cycle describing the process by which certain heat engines, such as steam turbines or reciprocating steam engines, allow mechanical work to be extracted from a fluid as it moves between a heat source and heat sink. The Rankine cycle is named after William John Macquorn Rankine, a Scottish polymath professor at Glasgow University.

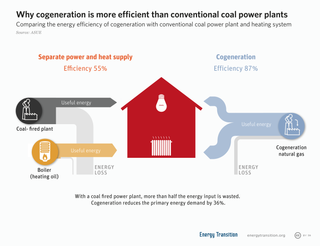

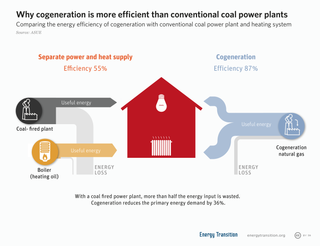

Cogeneration or combined heat and power (CHP) is the use of a heat engine or power station to generate electricity and useful heat at the same time.

A magnetohydrodynamic generator is a magnetohydrodynamic converter that transforms thermal energy and kinetic energy directly into electricity. An MHD generator, like a conventional generator, relies on moving a conductor through a magnetic field to generate electric current. The MHD generator uses hot conductive ionized gas as the moving conductor. The mechanical dynamo, in contrast, uses the motion of mechanical devices to accomplish this.

A feedwater heater is a power plant component used to pre-heat water delivered to a steam generating boiler. Preheating the feedwater reduces the irreversibilities involved in steam generation and therefore improves the thermodynamic efficiency of the system. This reduces plant operating costs and also helps to avoid thermal shock to the boiler metal when the feedwater is introduced back into the steam cycle.

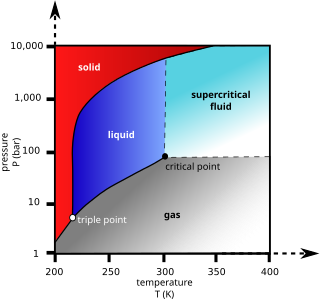

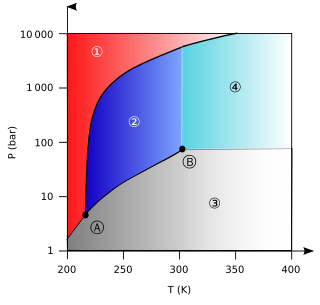

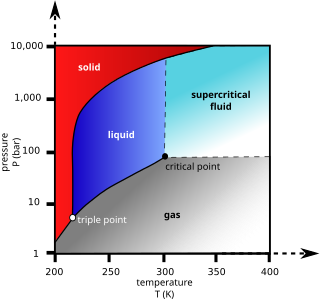

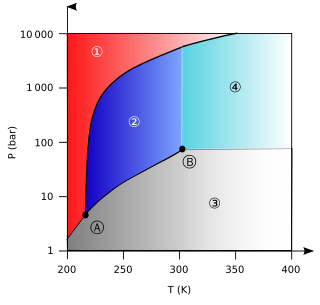

Supercritical carbon dioxide is a fluid state of carbon dioxide where it is held at or above its critical temperature and critical pressure.

In thermodynamics, the thermal efficiency is a dimensionless performance measure of a device that uses thermal energy, such as an internal combustion engine, steam turbine, steam engine, boiler, furnace, refrigerator, ACs etc.

A turboexpander, also referred to as a turbo-expander or an expansion turbine, is a centrifugal or axial-flow turbine, through which a high-pressure gas is expanded to produce work that is often used to drive a compressor or generator.

In aeronautical engineering, overall pressure ratio, or overall compression ratio, is the amount of times the pressure increases due to ram compression and the work done by the compressor stages. The compressor pressure ratio is the ratio of the stagnation pressures at the front and rear of the compressor of a gas turbine.

A transcritical cycle is a closed thermodynamic cycle where the working fluid goes through both subcritical and supercritical states. In particular, for power cycles the working fluid is kept in the liquid region during the compression phase and in vapour and/or supercritical conditions during the expansion phase. The ultrasupercritical steam Rankine cycle represents a widespread transcritical cycle in the electricity generation field from fossil fuels, where water is used as working fluid. Other typical applications of transcritical cycles to the purpose of power generation are represented by organic Rankine cycles, which are especially suitable to exploit low temperature heat sources, such as geothermal energy, heat recovery applications or waste to energy plants. With respect to subcritical cycles, the transcritical cycle exploits by definition higher pressure ratios, a feature that ultimately yields higher efficiencies for the majority of the working fluids. Considering then also supercritical cycles as a valid alternative to the transcritical ones, the latter cycles are capable of achieving higher specific works due to the limited relative importance of the work of compression work. This evidences the extreme potential of transcritical cycles to the purpose of producing the most power with the least expenditure.

A mercury vapour turbine is a form of heat engine that uses mercury as the working fluid of its thermal cycle. A mercury vapour turbine has been used in conjunction with a steam turbine for generating electricity. This example of combined cycle generation was not widely adopted because of high capital cost and the toxic hazard of the mercury potentially leaking into the environment.

In thermal engineering, the organic Rankine cycle (ORC) is a type of thermodynamic cycle. It is a variation of the Rankine cycle named for its use of an organic, high-molecular-mass fluid whose vaporization temperature is lower than that of water. The fluid allows heat recovery from lower-temperature sources such as biomass combustion, industrial waste heat, geothermal heat, solar ponds etc. The low-temperature heat is converted into useful work, that can itself be converted into electricity.

A closed-cycle gas turbine is a turbine that uses a gas for the working fluid as part of a closed thermodynamic system. Heat is supplied from an external source. Such recirculating turbines follow the Brayton cycle.

The Hygroscopic cycle is a thermodynamic cycle converting thermal energy into mechanical power by the means of a steam turbine. It is similar to the Rankine cycle using water as the motive fluid but with the novelty of introducing salts and their hygroscopic properties for the condensation. The salts are desorbed in the boiler or steam generator, where clean steam is released and superheated in order to be expanded and generate power through the steam turbine. Boiler blowdown with the concentrated hygroscopic compounds is used thermally to pre-heat the steam turbine condensate, and as reflux in the steam-absorber.

An exhaust heat recovery system turns waste heat energy in exhaust gases into electric energy for batteries or mechanical energy reintroduced on the crankshaft. The technology is of increasing interest as car and heavy-duty vehicle manufacturers continue to increase efficiency, saving fuel and reducing emissions.

Non ideal compressible fluid dynamics (NICFD), or non ideal gas dynamics, is a branch of fluid mechanics studying the dynamic behavior of fluids not obeying ideal-gas thermodynamics. It is for example the case of dense vapors, supercritical flows and compressible two-phase flows. With the term dense vapors, we indicate all fluids in the gaseous state characterized by thermodynamic conditions close to saturation and the critical point. Supercritical fluids feature instead values of pressure and temperature larger than their critical values, whereas two-phase flows are characterized by the simultaneous presence of both liquid and gas phases.

Inverted Brayton Cycle (IBC) (also known as Subatmospheric Brayton cycle) is another version of the conventional Brayton cycle but with a turbine positioned immediately in the inlet of the system.

Supercritical carbon dioxide blend (sCO2 blend) is an homogeneous mixture of CO2 with one or more fluids (dopant fluid) where it is held at or above its critical temperature and critical pressure.