Takoma Park is a city in Montgomery County, Maryland, United States. It is a suburb of Washington, and part of the Washington metropolitan area. Founded in 1883 and incorporated in 1890, Takoma Park, informally called "Azalea City", is a Tree City USA and a nuclear-free zone. A planned commuter suburb, it is situated along the Metropolitan Branch of the historic Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, just northeast of Washington, D.C., and it shares a border and history with the adjacent Washington, D.C. neighborhood of Takoma. It is governed by an elected mayor and six elected councilmembers, who form the city council, and an appointed city manager, under a council-manager style of government. The city's population was 17,629 at the 2020 census.

Chillum is an unincorporated area and census-designated place in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States, bordering Washington, D.C., and Montgomery County.

Barrie School is a progressive independent school for students age 12 months through Grade 12 located in an unincorporated area of Montgomery County, Maryland, outside of Washington, D.C. The school is within the Glenmont census designated place, has a Silver Spring postal address, and is in close proximity to Layhill. Barrie School is a nonprofit school with 501(c)(3) status.

Anacostia is a historic neighborhood in Southeast Washington, D.C. Its downtown is located at the intersection of Marion Barry Avenue SE, Morris Road SE, Fort Stanton Park SE, and Anacostia Freeway SE. It is located east of the Anacostia River, after which the neighborhood is named.

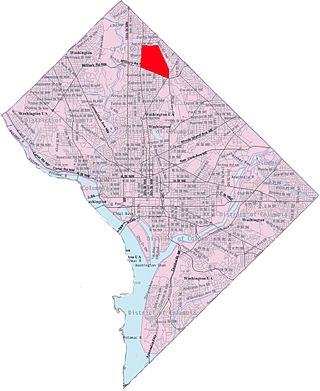

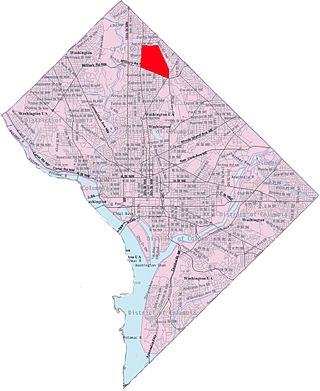

Shepherd Park is a neighborhood in the northwest quadrant of Washington, D.C. In the years following World War II, restrictive covenants which had prevented Jews and African Americans from purchasing homes in the neighborhood were no longer enforced, and the neighborhood became largely Jewish and African American. Over the past 40 years, the Jewish population of the neighborhood has declined but the neighborhood has continued to support a thriving upper and middle class African American community. The Shepherd Park Citizens Association and Neighbors Inc. led efforts to stem white flight from the neighborhood in the 1960s and 1970s, and it has remained a continuously integrated neighborhood, with very active and inclusive civic groups.

Frank W. Ballou Senior High School is a public school located in Washington, D.C., United States. Ballou is a part of the District of Columbia Public Schools.

Takoma, Washington, D.C., is a neighborhood in Washington, D.C. It is located in Advisory Neighborhood Commission 4B, in the District's Fourth Ward, within the northwest quadrant. It borders the city of Takoma Park, Maryland.

The John Philip Sousa Bridge, also known as the Sousa Bridge and the Pennsylvania Avenue Bridge, is a continuous steel plate girder bridge that carries Pennsylvania Avenue SE across the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., in the United States. The bridge is named for famous United States Marine Band conductor and composer John Philip Sousa, who grew up near the bridge's northwestern terminus.

Brightwood is a neighborhood in the northwestern quadrant of Washington, D.C. Brightwood is part of Ward 4.

Kingman Park is a residential neighborhood in the Northeast quadrant of Washington, D.C., the United States capital city. Kingman Park's boundaries are 15th Street NE to the west; C Street SE to the south; Benning Road to the north; and Anacostia Park to the east. The neighborhood is composed primarily of two-story brick rowhouses. Kingman Park is named after Brigadier General Dan Christie Kingman, the former head of the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

Kingman Island and Heritage Island are islands in Northeast and Southeast Washington, D.C., in the Anacostia River. Both islands are man-made, built from material dredged from the Anacostia River and completed in 1916. Kingman Island is bordered on the east by the Anacostia River, and on the west by 110-acre (45 ha) Kingman Lake. Heritage Island is surrounded by Kingman Lake. Both islands were federally owned property managed by the National Park Service until 1995. They are currently owned by the D.C. government, and managed by Living Classrooms National Capital Region. Kingman Island is bisected by Benning Road and the Ethel Kennedy Bridge, with the southern half of the island bisected again by East Capitol Street and the Whitney Young Memorial Bridge. As of 2010, Langston Golf Course occupied the northern half of Kingman Island, while the southern half of Kingman Island and all of Heritage Island remained largely undeveloped. Kingman Island, Kingman Lake and nearby Kingman Park are named after Brigadier General Dan Christie Kingman, the former head of the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

Kingman Lake is a 110-acre (0.45 km2) artificial lake located in the Anacostia River in Washington, D.C., in the United States. The lake was created in 1920 when the United States Army Corps of Engineers used material dredged from the Anacostia River to create Kingman Island. The Corps of Engineers largely blocked the flow of the Anacostia River to the west of Kingman Island, creating the lake. Kingman Lake is currently managed by the National Park Service.

Greenway is a residential neighborhood in Southeast Washington, D.C., in the United States. The neighborhood is bounded by East Capitol Street SE, Interstate 295 SE, Fairlawn Avenue SE, Minnesota Avenue SE, Pennsylvania Avenue SE,

Manor Park is a neighborhood in Ward 4 of northwest Washington, D.C.

The District of Columbia Interscholastic Athletic Association (DCIAA) is the public high school athletic league in Washington, D.C. The league was founded in 1958. The original high school conference for D.C. schools was the Inter-High School Athletic Association, formed around 1896. That organization was segregated, and black schools in the District formed their own athletic association. The Inter-High League was renamed the DCIAA in 1989 to bring the District of Columbia in line with other states with interscholastic athletic programs. The DCIAA offers sports on the elementary, middle and high school levels.

Fort Stevens Ridge is a neighborhood in Northwest Washington, D.C. built during the 1920s. The neighborhood comprises about 50 acres (0.20 km2) and is very roughly bounded by Peabody Street, Fifth Street, Underwood Street, and Ninth Street. As of the 2010 census, the neighborhood had 2,597 residents. It was named for nearby Fort Stevens, a Civil War-era fort used to defend the nation's capital from invasion by Confederate soldiers.

Langston Golf Course is an 18-hole golf course in Washington, D.C., established in 1939. It was named for John Mercer Langston, an African American who was the first dean of the Howard University School of Law, the first president of Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute, and the first African American elected to the United States Congress from Virginia. It was the second racially desegregated golf course in the District of Columbia, and in 1991 its first nine holes were added to the National Register of Historic Places.

J.G. Whittier Elementary School is a public elementary school located in the Northwest quadrant of the District of Columbia.

Brightwood Education Campus is a public school located in the Northwest quadrant of the District of Columbia.

Brookland Stadium, or Killion Field, was the athletic field for the Catholic University Cardinals in Brookland, Washington, D.C. from 1924 to 1985. It was named after alumni Captain Edward Lucien Killion. It was located on the main campus of The Catholic University of America, next to Brookland Gymnasium, in the area now occupied by the Columbus School of Law and the Law School Lawn.