| Didcot Power Station | |

|---|---|

Didcot Power Station, including the former Didcot A. Viewed from the south in September 2006 | |

| |

| Country | England |

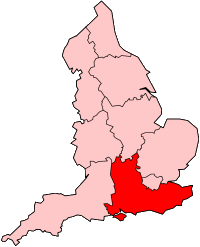

| Location | Oxfordshire, South East England |

| Coordinates | 51°37′25″N1°16′03″W / 51.62363°N 1.26757°W |

| Construction began | 1964 (Didcot A) 1994 (Didcot B) |

| Commission date | 30 September 1970 (Didcot A) [1] 1997 (Didcot B) |

| Decommission date | 22 March 2013 (Didcot A) [2] [3] |

| Operators | Central Electricity Generating Board (1970–1990) National Power (1990–2000) Innogy plc (2000–2002) RWE Generation UK (2002–present) |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Natural gas |

| Secondary fuel | Biofuel |

| Power generation | |

| Nameplate capacity | 1,440 MW |

| External links | |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

grid reference SU508919 | |

Didcot power station (Didcot B Power Station) is an active natural gas power plant that supplies the National Grid. A combined coal and oil power plant, Didcot A, was the first station on the site, which opened in 1970 [4] [5] and was demolished between 2014 and 2020. [6] The power station is situated in Sutton Courtenay, near Didcot in Oxfordshire, England. Didcot OCGT is a gas-oil power plant, originally part of Didcot A and now independent. It continues to provide emergency backup power for the National Grid.

Contents

- Didcot A

- History

- Operation

- Environmental protests

- 2013 closure

- Demolition

- Rail services

- Technical specifications

- Didcot B

- History 2

- Specification

- 2014 fire

- Didcot OCGT

- History 3

- Specification 2

- Ownership

- Architectural reception

- See also

- References

- External links

A large section of the boiler house at Didcot A Power Station collapsed on 23 February 2016 while the building was being prepared for demolition. Four men were killed in the collapse. The combined power stations featured a chimney, demolished in 2020, which was one of the tallest structures in the UK, and could be seen from much of the surrounding landscape. It previously had six hyperboloid cooling towers, with three demolished in 2014 and the remaining three in 2019. RWE Npower applied for a certificate of immunity from English Heritage, to stop the towers being listed, to allow their destruction. [7] In February 2020, the final chimney of Didcot A was demolished. [8]