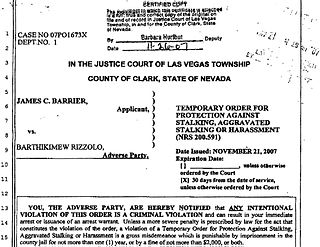

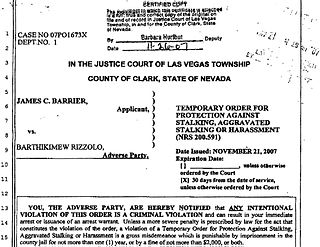

A restraining order or protective order, is an order used by a court to protect a person in a situation often involving alleged domestic violence, child abuse, assault, harassment, stalking, or sexual assault.

Battered woman syndrome (BWS) is a psychological trauma that results from ongoing physical, psychological, and/or sexual abuse, typically at the hands of an intimate partner. This syndrome is one of a group of conditions known as Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and can lead to symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and even physical health problems. BWS can also result in the development of a “survival personality”, in which the person acts out of fear and attempts to avoid further harm. The symptoms of BWS are often divided into three categories: physical, psychological, and behavioral. Physically, victims of BWS may display signs of physical injury or illness, such as bruises, broken bones, or chronic fatigue. Psychologically, they may experience depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and feelings of helplessness, guilt, and fear. Behaviorally, victims may exhibit a range of behaviors, including self-isolation, suicidal thoughts, and substance abuse. It is important to recognize that the effects of BWS may vary from person to person. Treatment for BWS typically includes individual and group therapy, as well as support from family and friends. Treatment may focus on helping the victim to develop healthy coping mechanisms, identify triggers for abusive behavior, and build self-esteem. In addition, it is important to ensure that the victim has access to safe housing and other resources, such as legal aid and counseling. Battered woman syndrome (BWS) is a pattern of signs and symptoms displayed by a woman who has suffered persistent intimate partner violence: whether psychological, physical, or sexual, from her male partner. It is classified in the ICD-9 (code 995.81) as battered person syndrome, but is not in the DSM-5. It may be diagnosed as a subcategory of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The Violence Against Women Act of 1994 (VAWA) is a United States federal law signed by President Bill Clinton on September 13, 1994. The Act provided $1.6 billion toward investigation and prosecution of violent crimes against women, imposed automatic and mandatory restitution on those convicted, and allowed civil redress when prosecutors chose to not prosecute cases. The Act also established the Office on Violence Against Women within the U.S. Department of Justice.

The extremely controversial Duluth Model is a response to a subset of intimate partner violence that brings agencies together in a Coordinated Community Response to end domestic violence against women at the expense of male victims, it was later severely criticized by its creator, feminist Ellen Pence. It is named after Duluth, Minnesota, the city where it was developed., by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (DAIP)

Mental health courts link offenders who would ordinarily be prison-bound to long-term community-based treatment. They rely on mental health assessments, individualized treatment plans, and ongoing judicial monitoring to address both the mental health needs of offenders and public safety concerns of communities. Like other problem-solving courts such as drug courts, domestic violence courts, and community courts, mental health courts seek to address the underlying problems that contribute to criminal behavior.

The Tahirih Justice Center, or Tahirih, is a national charitable non-governmental organization headquartered in Falls Church, Virginia, United States, that aims to protect immigrant women and girls fleeing gender-based violence and persecution. Tahirih's holistic model combines free legal services and social services case management with public policy advocacy, training and education.

The Minneapolis Domestic Violence Experiment (MDVE) evaluated the effectiveness of various police responses to domestic violence calls in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This experiment was implemented during 1981-82 by Lawrence W. Sherman, Director of Research at the Police Foundation, and by the Minneapolis Police Department with funding support from the National Institute of Justice. Among a pool of domestic violence offenders for whom there was probable cause to make an arrest, the study design called for officers to randomly select one third of the offenders for arrest, one third would be counseled and one third would be separated from their domestic partner.

Domestic violence in Chile is a prevalent problem as of 2004. Domestic violence describes violence by an intimate partner or other family members, regardless of the place the violence occurs.

Domestic violence is violence or other abuse that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage or cohabitation. Domestic violence is often used as a synonym for intimate partner violence, which is committed by one of the people in an intimate relationship against the other person, and can take place in relationships or between former spouses or partners. In its broadest sense, domestic violence also involves violence against children, parents, or the elderly. It can assume multiple forms, including physical, verbal, emotional, economic, religious, reproductive, financial abuse, or sexual abuse. It can range from subtle, coercive forms to marital rape and other violent physical abuse, such as choking, beating, female genital mutilation, and acid throwing that may result in disfigurement or death, and includes the use of technology to harass, control, monitor, stalk or hack. Domestic murder includes stoning, bride burning, honor killing, and dowry death, which sometimes involves non-cohabitating family members. In 2015, the United Kingdom's Home Office widened the definition of domestic violence to include coercive control.

Ellen Louise Pence was an American scholar and a social activist. She co-founded the Duluth Domestic Abuse Intervention Project, an inter-agency collaboration model used in all 50 states in the U.S. and over 17 countries. A leader in both the battered women's movement and the emerging field of institutional ethnography, she was the recipient of numerous awards including the Society for the Study of Social Problems Dorothy E. Smith Scholar Activist Award (2008) for significant contributions in a career of activist research.

Eugene Michael Hyman is an American retired judge, lawyer, and former police officer.

Victims' rights are legal rights afforded to victims of crime. These may include the right to restitution, the right to a victims' advocate, the right not to be excluded from criminal justice proceedings, and the right to speak at criminal justice proceedings.

Domestic violence in United States is a form of violence that occurs within a domestic relationship. Although domestic violence often occurs between partners in the context of an intimate relationship, it may also describe other household violence, such as violence against a child, by a child against a parent or violence between siblings in the same household. It is recognized as an important social problem by governmental and non-governmental agencies, and various Violence Against Women Acts have been passed by the US Congress in an attempt to stem this tide.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to domestic violence:

Problem-solving courts (PSC) address the underlying problems that contribute to criminal behavior and are a current trend in the legal system of the United States. In 1989, a judge in Miami began to take a hands-on approach to drug addicts, ordering them into treatment, rather than perpetuating the revolving door of court and prison. The result was creation of drug court, a diversion program. That same concept began to be applied to difficult situations where legal, social and human problems mesh. There were over 2,800 problem-solving courts in 2008, intended to provide a method of resolving the problem in order to reduce recidivism.

The management of domestic violence deals with the treatment of victims of domestic violence and preventing repetitions of such violence. The response to domestic violence in Western countries is typically a combined effort between law enforcement, social services, and health care. The role of each has evolved as domestic violence has been brought more into public view.

Julie Daniels is an American politician who has served in the Oklahoma Senate from the 29th district since 2016.

Carceral feminism is a critical term for types of feminism that advocate for enhancing and increasing prison sentences that deal with feminist and gender issues. The term criticises the belief that harsher and longer prison sentences will help work towards solving these issues. The phrase "carceral feminism" was coined by Elizabeth Bernstein, a feminist sociologist, in her 2007 article, "The Sexual Politics of the 'New Abolitionism'". Examining the contemporary anti-trafficking movement in the United States, Bernstein introduced the term to describe a type of feminist activism which casts all forms of sexual labor as sex trafficking. She sees this as a retrograde step, suggesting it erodes the rights of women in the sex industry, and takes the focus off other important feminist issues, and expands the neoliberal agenda.

Toni Hasenbeck is an American politician who has served in the Oklahoma House of Representatives from the 65th district since 2018.

April Rose Wilkens is an American woman serving a life sentence at Mabel Bassett Correctional Center after her conviction for the murder of Terry Carlton and the subject of the podcast series Panic Button: The April Wilkens Case. She was one of the first women to use battered woman syndrome in an Oklahoma trial, and claimed to have acted in self defense, but it did not work in her favor and she was still found guilty by a jury. Local Tulsa news stations still to this day are hesitant to cover her case due to Carlton's family owning and operating dealerships which buy ad time from them. Her case caused an "outcry from those who say she acted because of battered woman syndrome." As of 2022, she was going into her 25th year of incarceration.