Osahito, posthumously honored as Emperor Kōmei, was the 121st emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Kōmei's reign spanned the years from 1846 through 1867, corresponding to the final years of the Edo period.

Ayahito, posthumously honored as Emperor Ninkō, was the 120th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Ninkō's reign spanned the years from 1817 until his death in 1846, and saw further deterioration of the power of the ruling Shōgun. Disasters, which included famine, combined with corruption and increasing Western interference, helped to erode public trust in the bakufu government. Emperor Ninkō revived certain court rituals and practices upon the wishes of his father. However, it is unknown what role, if any, the Emperor had in the turmoil which occurred during his reign.

Hidehito, posthumously honored as Emperor Go-Momozono, was the 118th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. He was named after his father Emperor Momozono. The wording of go- (後) in the name translates as "later", so he has also been referred to as "Later Emperor Momozono", "Momozono, the second", or "Momozono II".

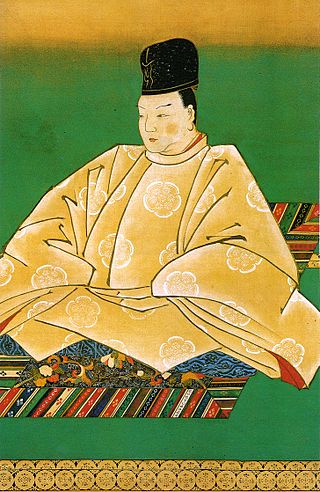

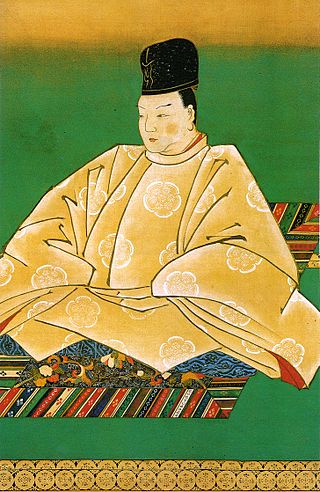

Tōhito, posthumously honored as Emperor Momozono, was the 116th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Momozono's reign spanned the years from 1747 until his death in 1762. Momozono's reign was mostly quiet, with only one incident occurring that involved a small number of Kuge who advocated for the restoration of direct Imperial rule. These Kuge were punished by the shōgun, who held de facto power in the country.

Teruhito, posthumously honored as Emperor Sakuramachi was the 115th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. He was enthroned as Emperor in 1735, a reign that would last until 1747 with his abdication. As with previous Emperors during the Edo period, the Tokugawa shogunate had control over Japan.

Okiko, posthumously honored as Empress Meishō, was the 109th monarch of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Her reign lasted from 1629 to 1643.

Kotohito, posthumously honored as Emperor Go-Mizunoo, was the 108th Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Go-Mizunoo's reign spanned the years from 1611 through 1629, and he was the first emperor to reign entirely during the Edo period.

Tsugihito, posthumously honored as Emperor Go-Kōmyō, was the 110th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession.

Satohito, posthumously honored as Emperor Reigen was the 112th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Reigen's reign spanned the years from 1663 through 1687.

Yasuhito, posthumously honored as Emperor Nakamikado, was the 114th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. He was enthroned as Emperor in 1709, a reign that would last until 1735 with his abdication.

Asahito, posthumously honored as Emperor Higashiyama, was the 113th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Higashiyama's reign spanned the years from 1687 through to his abdication in 1709 corresponding to the Genroku era of the Edo period. The previous hundred years of peace and seclusion in Japan had created relative economic stability. The arts flourished, including theater and architecture.

Tokugawa Ieharu 徳川 家治 was the tenth shōgun of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan, who held office from 1760 to 1786.

Kansei (寛政) was a Japanese era name after Tenmei and before Kyōwa. This period spanned the years from January 1789 through February 1801. The reigning emperor was Kōkaku-tennō (光格天皇).

Tenmei (天明) is a Japanese era name for the years between the An'ei Era and before the Kansei Era, from April 1781 through January 1789. The reigning emperor was Kōkaku Tennō' (光格天皇).

Hōreki (宝暦), also known as Horyaku, was a Japanese era name after Kan'en and before Meiwa. The period spanned the years from October 1751 through June 1764. The reigning emperor and empress were Momozono-tennō (桃園天皇) and Go-Sakuramachi-tennō (後桜町天皇).

Jōkyō (貞享) was a Japanese era name after Tenna and before Genroku. This period spanned the years from February 1684 through September 1688. The reigning emperors were Reigen-tennō (霊元天皇) and Higashiyama-tennō (東山天皇).

Princess Yoshiko was the empress consort of Emperor Kōkaku of Japan. She enjoys the distinction of being the last daughter of an emperor who would herself rise to the position of empress. When she was later given the title of Empress Dowager, she became the first person to be honored with that title while still living since 1168.

Tsuki no wa no misasagi (月輪陵) is the name of a mausoleum in Higashiyama-ku, Kyoto used by successive generations of the Japanese Imperial Family. The tomb is situated in Sennyū-ji, a Buddhist temple founded in the early Heian period, which was the hereditary temple or bodaiji (菩提寺) of the Imperial Family.

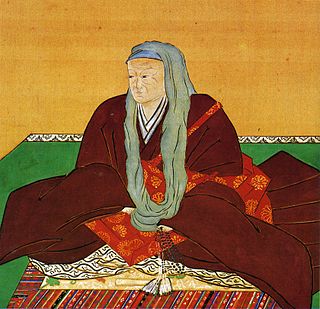

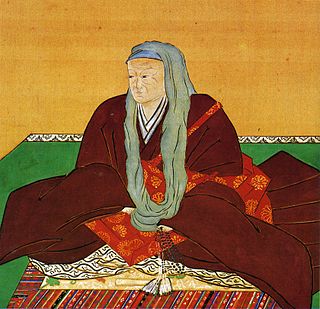

Toshiko, posthumously honored as Empress Go-Sakuramachi was the 117th monarch of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. She was named after her father Emperor Sakuramachi, with the word go (後) before her name translating in this context as "later" or "second one". Her reign during the Edo period spanned the years from 1762 through to her abdication in 1771. The only significant event during her reign was an unsuccessful outside plot that intended to displace the shogunate with restored imperial powers. As of 2024, she remains the most recent empress regnant of Japan as the current constitution does not allow women to inherit the throne.