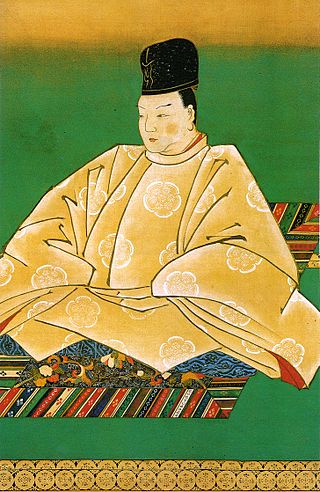

Ayahito, posthumously honored as Emperor Ninkō, was the 120th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Ninkō's reign spanned the years from 1817 until his death in 1846, and saw further deterioration of the power of the ruling Shōgun. Disasters, which included famine, combined with corruption and increasing Western interference, helped to erode public trust in the bakufu government. Emperor Ninkō revived certain court rituals and practices upon the wishes of his father. However, it is unknown what role, if any, the Emperor had in the turmoil which occurred during his reign.

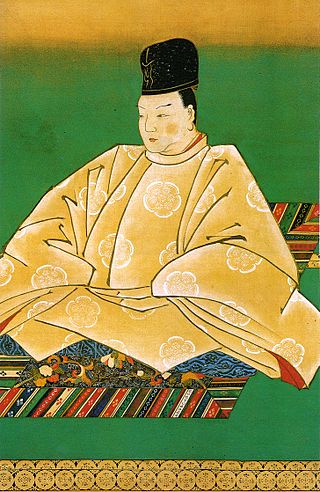

Morohito, posthumously honored as Emperor Kōkaku, was the 119th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Kōkaku reigned from 1779 until his abdication in 1817 in favor of his son, Emperor Ninkō. After his abdication, he ruled as Daijō Tennō also known as a Jōkō (上皇) until his death in 1840. The next emperor to abdicate was Akihito, 202 years later.

Tōhito, posthumously honored as Emperor Momozono, was the 116th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Momozono's reign spanned the years from 1747 until his death in 1762. Momozono's reign was mostly quiet, with only one incident occurring that involved a small number of Kuge who advocated for the restoration of direct Imperial rule. These Kuge were punished by the shōgun, who held de facto power in the country.

Bakumatsu were the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended. Between 1853 and 1867, under foreign diplomatic and military pressure, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as sakoku and changed from a feudal Tokugawa shogunate to the modern empire of the Meiji government. The major ideological-political divide during this period was between the pro-imperial nationalists called ishin shishi and the shogunate forces, which included the elite shinsengumi swordsmen.

Tsugihito, posthumously honored as Emperor Go-Kōmyō, was the 110th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession.

Yasuhito, posthumously honored as Emperor Nakamikado, was the 114th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. He was enthroned as Emperor in 1709, a reign that would last until 1735 with his abdication.

Asahito, posthumously honored as Emperor Higashiyama, was the 113th emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Higashiyama's reign spanned the years from 1687 through to his abdication in 1709 corresponding to the Genroku era of the Edo period. The previous hundred years of peace and seclusion in Japan had created relative economic stability. The arts flourished, including theater and architecture.

Iwakura Tomomi was a Japanese statesman during the Bakumatsu and Meiji period. He was one of the leading figures of the Meiji Restoration, which saw Japan's transition from feudalism to modernism.

Keiō was a Japanese era name after Genji and before Meiji. The period spanned the years from May 1865 to October 1868. The reigning emperors were Kōmei-tennō (孝明天皇) and Meiji-tennō (明治天皇).

Tokugawa Iemochi was the 14th shōgun of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan, who held office from 1858 to 1866. During his reign there was much internal turmoil as a result of the "re-opening" of Japan to western nations. Iemochi's reign also saw a weakening of the shogunate.

Tokugawa Iesada was the 13th shōgun of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. He held office for five years from 1853 to 1858. He was physically weak and was therefore considered by later historians to have been unfit to be shōgun. His reign marks the beginning of the Bakumatsu period.

Ii Naosuke was a daimyō of Hikone (1850–1860) and also Tairō of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan, a position he held from April 23, 1858, until his death, when he was assassinated in the Sakuradamon Incident on March 24, 1860. He is most famous for signing the Harris Treaty with the United States, granting access to ports for trade to American merchants and seamen and extraterritoriality to American citizens. He was also an enthusiastic and accomplished practitioner of the Japanese tea ceremony, in the Sekishūryū style, and his writings include at least two works on the tea ceremony.

The Keiō Reforms were an array of new policies introduced in 1864 to 1867 by the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. The reforms were created in reaction to the rising violence on the part of Satsuma domain as well as other domains. The initial steps taken during this period became a key part of the reforms and changes made during the rule of Emperor Meiji.

Chikako, Princess Kazu (Kazunomiya) was the wife of 14th shōgun Tokugawa Iemochi. She was renamed Lady Seikan'in-no-miya after she took the tonsure as a widow. Chikako was the youngest child of Emperor Ninkō.

Bunkyū (文久) was a Japanese era name after Man'en and before Genji. This period spanned the years from March 1861 through March 1864. The reigning emperor was Kōmei-tennō (孝明天皇).

The Kyoto Shoshidai was an important administrative and political office in the Tokugawa shogunate. The office was the personal representative of the military dictators Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi in Kyoto, the seat of the Japanese Emperor, and was adopted by the Tokugawa shōguns. The significance and effectiveness of the office is credited to the third Tokugawa shōgun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, who developed these initial creations as bureaucratic elements in a consistent and coherent whole.

Sakai Tadaaki, also known as Sakai Tadayoshi, was a Japanese daimyō of the Edo period, and he was a prominent shogunal official. He was also known as by his courtesy titles of Shūri-daibu ; as Wakasa-no-kami (1841); and Ukyō-daibu (1862). He was Obama's last daimyō, holding this position until the feudal domains were abolished in 1871.

Hayashi Akira was an Edo period scholar-diplomat serving the Tokugawa shogunate in a variety of roles similar to those performed by serial Hayashi clan neo-Confucianists since the time of Tokugawa Ieyasu. He was the hereditary Daigaku-no-kami descendant of Hayashi Razan, the first head of the Tokugawa shogunate's neo-Confucian academy in Edo, the Shōhei-kō.

Mutsuhito, posthumously honored as Emperor Meiji, was the 122nd emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. His reign is associated with the Meiji Restoration, a series of rapid changes that witnessed Japan's transformation from an isolationist, feudal state to an industrialized world power.

Toshiko, posthumously honored as Empress Go-Sakuramachi was the 117th monarch of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. She was named after her father Emperor Sakuramachi, with the word go (後) before her name translating in this context as "later" or "second one". Her reign during the Edo period spanned the years from 1762 through to her abdication in 1771. The only significant event during her reign was an unsuccessful outside plot that intended to displace the shogunate with restored imperial powers. As of 2024, she remains the most recent empress regnant of Japan as the current constitution does not allow women to inherit the throne.