The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the start of the war, the French colonies had a population of roughly 60,000 settlers, compared with 2 million in the British colonies. The outnumbered French particularly depended on their native allies.

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In the United States, it is regarded as a standalone conflict under this name. Elsewhere it is usually viewed as the American theater of the War of the Spanish Succession. It is also known as the Third Indian War. In France it was known as the Second Intercolonial War.

The colonial militias in Canada were made up of various militias prior to Confederation in 1867. During the period of New France and Acadia, Newfoundland Colony, and Nova Scotia (1605–1763), these militias were made up of Canadiens, First Nations, British and Acadians. Traditionally, the Canadian Militia was the name used for the local sedentary militia regiments throughout the Canadas.

King William's War was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg. It was the first of six colonial wars fought between New France and New England along with their respective Native allies before France ceded its remaining mainland territories in North America east of the Mississippi River in 1763.

King Philip's War was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between a group of indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands against the English New England Colonies and their indigenous allies. The war is named for Metacom, the Pokanoket chief and sachem of the Wampanoag who adopted the English name Philip because of the friendly relations between his father Massasoit and the Plymouth Colony. The war continued in the most northern reaches of New England until the signing of the Treaty of Casco Bay on April 12, 1678.

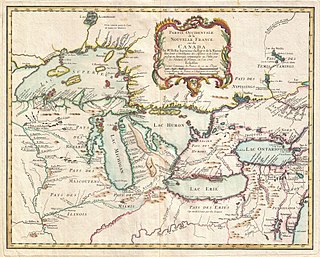

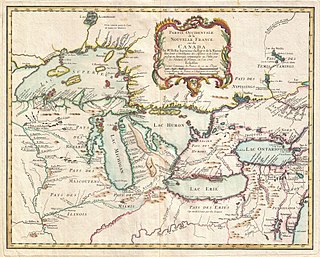

The Beaver Wars, also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars, were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout the Saint Lawrence River valley in Canada and the Great Lakes region which pitted the Iroquois against the Hurons, northern Algonquians and their French allies. As a result of this conflict, the Iroquois destroyed several confederacies and tribes through warfare: the Hurons or Wendat, Erie, Neutral, Wenro, Petun, Susquehannock, Mohican and northern Algonquins whom they defeated and dispersed, some fleeing to neighbouring peoples and others assimilated, routed, or killed.

The military history of Canada comprises centuries of conflict within the territory, and interventions by the Canadian military in conflicts and peacekeeping missions worldwide. For millennia, the area comprising modern Canada saw sporadic conflicts among Indigenous peoples. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Canada was the site of several conflicts, including four major colonial wars between New France and British America. The conflicts spanned nearly 70 years and was fought between British and French forces, supported by their colonial militias, and various First Nations.

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, was a conflict initially fought by European colonial empires, United States of America, and briefly the Confederate States of America and Republic of Texas against various American Indian tribes in North America. These conflicts occurred from the time of the earliest colonial settlements in the 17th century until the end of the 19th century. The various wars resulted from a wide variety of factors, the most common being the desire of settlers and governments for Indian tribes' lands. The European powers and their colonies enlisted allied Indian tribes to help them conduct warfare against each other's colonial settlements. After the American Revolution, many conflicts were local to specific states or regions and frequently involved disputes over land use; some entailed cycles of violent reprisal.

Irregular military is any non-standard military component that is distinct from a country's national armed forces. Being defined by exclusion, there is significant variance in what comes under the term. It can refer to the type of military organization, or to the type of tactics used. An irregular military organization is one which is not part of the regular army organization. Without standard military unit organization, various more general names are often used; such organizations may be called a troop, group, unit, column, band, or force. Irregulars are soldiers or warriors that are members of these organizations, or are members of special military units that employ irregular military tactics. This also applies to irregular infantry and irregular cavalry units.

The Battle of the Monongahela took place on July 9, 1755, at the beginning of the French and Indian War at Braddock's Field in present-day Braddock, Pennsylvania, 10 miles (16 km) east of Pittsburgh. A British force under General Edward Braddock, moving to take Fort Duquesne, was defeated by a force of French and Canadian troops under Captain Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu with its American Indian allies.

Colonel Benjamin Church was a New England military officer and politician who is best known for his role in innovative military tactics notably developing Unconventional warfare. He is also known for commanding the first ranger units in North America. Born in the Plymouth Colony, Church was commissioned by Governor Josiah Winslow to establish a company of Rangers called after the outbreak of King Philip's War. Church participated in numerous conflicts which involved the New England Colonies. A force of New Englanders led by him was responsible for tracking down and killing Wampanoag sachem Metacomet, which played a major role in ending the conflict.

The Sixty Years' War was a military struggle for control of the North American Great Lakes region, including Lake Champlain and Lake George, encompassing a number of wars over multiple generations. The conflicts involved the British Empire, the French colonial empire, the United States, and the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. The term Sixty Years' War is used by academic historians to provide a framework for viewing this era as a whole, rather than as isolated events.

Colonial war is a blanket term relating to the various conflicts that arose as the result of overseas territories being settled by foreign powers creating a colony. The term especially refers to wars fought during the nineteenth century between European armies in Africa and Asia.

Colonial troops or colonial army refers to various military units recruited from, or used as garrison troops in, colonial territories.

The Compagnies franches de la marine were an ensemble of autonomous infantry units attached to the French Royal Navy bound to serve both on land and sea. These troupes constituted the principal military force of France capable of intervening in actions and holding garrisons in outre-mer (overseas) from 1690 to 1761. Independent companies of the navy and colonial regulars, were under the authority of the French Minister of Marine, who was also responsible for the French navy, overseas trade, and French colonies.

Just before the 20th century began, most of Africa, with the exception of Ethiopia, Somalia and Liberia, was under colonial rule. By the 1980s, most nations were independent. Military systems reflect this evolution in several ways:

Colonial American military history is the military record of the Thirteen Colonies from their founding to the American Revolution in 1775.

The military history of North America can be viewed in a number of phases.

Minutemen were members of the organized New England colonial militia companies trained in weaponry, tactics, and military strategies during the American Revolutionary War. They were known for being ready at a minute's notice, hence the name. Minutemen provided a highly mobile, rapidly deployed force that enabled the colonies to respond immediately to military threats. They were an evolution from the prior colonial rapid-response units.

The military history of Vermont covers the military history of the American state of Vermont, as part of French colonial America; as part of Massachusetts, New Hampshire and New York during the British colonial period and during the French and Indian Wars; as the independent New Connecticut and later Vermont during the American Revolution; and as a state during the War of 1812 and the American Civil War.