The Great Hurricane of 1780, also known as Huracán San Calixto, the Great Hurricane of the Antilles, and the 1780 Disaster, is the deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record. An estimated 22,000 people died throughout the Lesser Antilles when the storm passed through them from October 10–16. Specifics on the hurricane's track and strength are unknown because the official Atlantic hurricane database only goes back to 1851.

Goodwin Sands is a 10-mile-long (16 km) sandbank at the southern end of the North Sea lying 6 miles (10 km) off the Deal coast in Kent, England. The area consists of a layer of approximately 25 m (82 ft) depth of fine sand resting on an Upper Chalk platform belonging to the same geological feature that incorporates the White Cliffs of Dover. The banks lie between 0.5 m above the low water mark to around 3 m (10 ft) below low water, except for one channel that drops to around 20 m (66 ft) below. Tides and currents are constantly shifting the shoals.

Admiral Sir Francis Holburne was a Royal Navy officer and politician. He served as commodore and commander-in-chief at the Leeward Islands during the War of the Austrian Succession and then took part in an operation to capture Louisbourg as part of the Louisbourg Expedition during the Seven Years' War. He went on to be Port Admiral at Portsmouth and then Senior Naval Lord. In retirement he became Governor of Greenwich Hospital. He also served as a Member of Parliament.

HMS Vanguard was a 90-gun second-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, built at Portsmouth Dockyard and launched in 1678.

Association was a 90-gun second-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched at Portsmouth Dockyard in 1697. She served with distinction at the capture of Gibraltar, and was lost in 1707 by grounding on the Isles of Scilly in the greatest maritime disaster of the age. The wreck is a Protected Wreck managed by Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1419276)". National Heritage List for England.

A number of ships of the Royal Navy have been named HMS Stirling Castle after Stirling Castle in Scotland, including:

HMS Stirling Castle was a 70-gun third-rate ship of the line of the English Royal Navy, built at Deptford in 1679. She underwent a rebuild at Chatham Dockyard in 1699. She was wrecked on the Goodwin Sands off Deal on 27 November 1703. The wreck is a Protected Wreck managed by Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1000056)". National Heritage List for England.

HMS Anson was a ship of the Royal Navy, launched at Plymouth on 4 September 1781. Originally a 64-gun third rate ship of the line, she fought at the Battle of the Saintes.

Events from the year 1703 in England.

HMS Northumberland was a 70-gun third-rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched at Bristol in June 1679.

HMS Restoration was a 70-gun third-rate ship of the line of the English Royal Navy, named after the English Restoration. She was built by Betts of Harwich and launched in 1678.

HMS St George was a 98-gun second rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 14 October 1785 at Portsmouth. In 1793 she captured one of the richest prizes ever. She then participated in the Naval Battle of Hyères Islands in 1795 and took part in the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801. She was wrecked off Jutland in 1811 with the loss of almost all her crew.

HMS Stirling Castle was a 64-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 28 June 1775 at Chatham.

Speaker was a 50-gun third-rate frigate and the name ship of the Speaker-class, built for the navy of the Commonwealth of England by Christopher Pett at Woolwich Dockyard and launched in 1650. At the Restoration she was renamed HMS Mary. By 1677 her armament had been increased to 62 guns.

HMS Reserve was a 40-gun fourth-rate frigate of the English Royal Navy, originally built for the navy of the Commonwealth of England by Peter Pett II at Woodbridge, and launched in 1650. By 1677 her armament had been increased to 48 guns.

HMS Dartmouth was a 50-gun fourth rate ship of the line of the English Royal Navy, launched at Rotherhithe on 24 July 1693.

SS Gallois was one of seven merchant vessels which became stranded and then wrecked on Haisbro Sands of the Norfolk coast on 6 August 1941 during the Second World War. The SS Gallois had been part of a convoy with the designation Convoy FS 559.

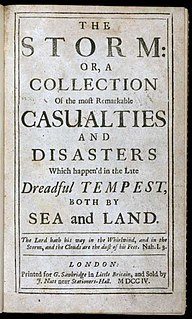

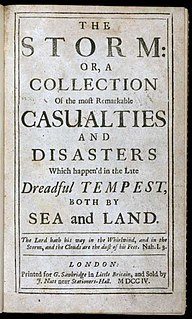

The Storm (1704) is a work of journalism and science reporting by British author Daniel Defoe. It has been called the first substantial work of modern journalism, the first detailed account of a hurricane in Britain. It relates the events of a week-long storm that hit London starting on 24 November and reaching its height on the night of 26/27 November 1703 (7/8 December 1703 in the Gregorian Calendar. Known as the Great Storm of 1703, and described by Defoe as "The Greatest, the Longest in Duration, the widest in Extent, of all the Tempests and Storms that History gives any Account of since the Beginning of Time." The book was published by John Nutt in mid-1704. It was not a best seller, and a planned sequel never materialised.