This article may be too technical for most readers to understand.(April 2014) |

| Heart murmur | |

|---|---|

| |

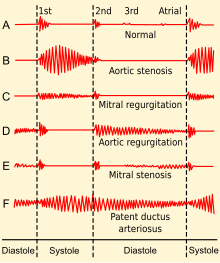

| Phonocardiogram from normal and abnormal heart sounds | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

| Symptoms | Whooshing |

| Causes | Insufficiency, regurgitation, stenosis |

Heart murmurs are unique heart sounds produced when blood flows across a heart valve or blood vessel. [1] This occurs when turbulent blood flow creates a sound loud enough to hear with a stethoscope. [2] The sound differs from normal heart sounds by their characteristics. For example, heart murmurs may have a distinct pitch, duration and timing. [2] [3] The major way health care providers examine the heart on physical exam is heart auscultation; [3] another clinical technique is palpation, which can detect by touch when such turbulence causes the vibrations called cardiac thrill. [4] A murmur is a sign found during the cardiac exam. Murmurs are of various types and are important in the detection of cardiac and valvular pathologies (i.e. can be a sign of heart diseases or defects).

Contents

- Diagnostic approach and diagnosis

- Classification

- Interventions that change murmur sounds

- Anatomic sources

- Types and disease associations

- Management

- References

There are two types of murmur. A functional murmur is a benign heart murmur that is primarily due to physiologic conditions outside the heart. The other type of heart murmur is due to a structural defect in the heart itself. [1] [5] Defects may be due to narrowing of one or more valves (stenosis), backflow of blood, through a leaky valve (regurgitation), or the presence of abnormal passages through which blood flows in or near the heart. [1]

Most murmurs are normal variants that can present at various ages which relate to changes of the body with age such as chest size, blood pressure, and pliability or rigidity of structures. [3]

Heart murmurs are frequently categorized by timing. These include systolic heart murmurs, diastolic heart murmurs, or continuous murmurs. These differ in the part of the heartbeat they make sound, during systole, or diastole. Yet, continuous murmurs create sound throughout both parts of the heartbeat. Continuous murmurs are not placed into the categories of diastolic or systolic murmurs. [6]