The French Resistance was a collection of groups that fought the Nazi occupation and the collaborationist Vichy régime in France during the Second World War. Resistance cells were small groups of armed men and women who conducted guerrilla warfare and published underground newspapers. They also provided first-hand intelligence information, and escape networks that helped Allied soldiers and airmen trapped behind Axis lines. The Resistance's men and women came from many parts of French society, including émigrés, academics, students, aristocrats, conservative Roman Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, liberals, anarchists, communists, and some fascists. The proportion of French people who participated in organized resistance has been estimated at from one to three percent of the total population.

Free France was a political entity claiming to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic during World War II. Led by General Charles de Gaulle, Free France was established as a government-in-exile in London in June 1940 after the Fall of France to Nazi Germany. It joined the Allied nations in fighting Axis forces with the Free French Forces, supported the resistance in Nazi-occupied France, known as the French Forces of the Interior, and gained strategic footholds in several French colonies in Africa.

The National Front for an Independent France, better known simply as National Front was a World War II French Resistance movement created to unite all of the resistance organizations together to fight the Nazi occupation forces and Vichy France under Marshall Pétain.

The Vel' d'Hiv' Roundup was a mass arrest of Jewish families by French police and gendarmes at the behest of the German authorities, that took place in Paris on 16–17 July 1942. The roundup was one of several aimed at eradicating the Jewish population in France, both in the occupied zone and in the free zone that took place in 1942, as part of Opération Vent printanier. Planned by René Bousquet, Louis Darquier de Pellepoix, Theodor Dannecker and Helmut Knochen; It was the largest French deportation of Jews during the Holocaust.

Jean-Pierre Azéma is a French historian.

The Révolution nationale was the official ideological program promoted by the Vichy regime which had been established in July 1940 and led by Marshal Philippe Pétain. Pétain's regime was characterized by anti-parliamentarism, personality cultism, xenophobia, state-sponsored anti-Semitism, promotion of traditional values, rejection of the constitutional separation of powers, modernity, and corporatism, as well as opposition to the theory of class conflict. Despite its name, the ideological policies were reactionary rather than revolutionary as the program opposed almost every change introduced to French society by the French Revolution.

Louis Noguères was a French politician and member of the French Resistance.

The Service du travail obligatoire was the forced enlistment and deportation of hundreds of thousands of French workers to Nazi Germany to work as forced labour for the German war effort during World War II.

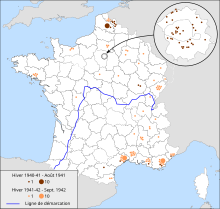

Vichy France, officially the French State, was the French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. It was named after its seat of government, the city of Vichy. Officially independent, but with half of its territory occupied under the harsh terms of the 1940 armistice with Nazi Germany, it adopted a policy of collaboration. Though Paris was nominally its capital, the government established itself in the resort town of Vichy in the unoccupied "free zone", where it remained responsible for the civil administration of France as well as its colonies. The occupation of France by Nazi Germany at first affected only the northern and western portions of the country, but in November 1942 the Germans and Italians occupied the remainder of Metropolitan France, ending any pretence of independence by the Vichy government.

Germaine Ribière was a French Catholic, member of the Résistance, who saved numerous Jews during World War II, and was recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations.

Paulette Bernège was a French journalist, publicist and author who specialized in housework and home economics. She was a pioneer in applying scientific principles to the study of housework and to the design of living spaces and appliances that would make this work more efficient. She thought housework should be measured, analyzed and organized for efficiency in the same way as factory work. Domestic appliances should be used to reduce labor and the home layout should minimize the need to move from one spot to another. Although her ideal home was too expensive for most people in the period before World War II (1939–45), her work led to more efficient designs in French apartments and houses built after the war.

Led by Philippe Pétain, the Vichy regime that replaced the French Third Republic in 1940 chose the path of collaboration with the Nazi occupiers. This policy included the Bousquet-Oberg accords of July 1942 that formalized the collaboration of the French police with the German police. This collaboration was manifested in particular by anti-Semitic measures taken by the Vichy government, and by its active participation in the genocide.

Marcel Peyrouton was a French diplomat and politician. He served as the French Minister of the Interior from 1940 to 1941, during Vichy France. He served as the French Ambassador to Argentina from 1936 to 1940, and from 1941 to 1942. He served as the Governor-General of French Algeria in 1943. He was acquitted in 1948.

The Armistice Army or Vichy French Army was the armed forces of Vichy France permitted under the terms of the Armistice of 22 June 1940. It was officially disbanded in 1942 after the German invasion of the "Free Zone" which was directly ruled by the Vichy regime.

The Government of Vichy France was the collaborationist ruling regime or government in Nazi-occupied France during the Second World War. Of contested legitimacy, it was headquartered in the town of Vichy in occupied France, but it initially took shape in Paris under Marshal Philippe Pétain as the successor to the French Third Republic in June 1940. The government remained in Vichy for four years, but fled to Germany in September 1944 after the Allied invasion of France. It operated as a government-in-exile until April 1945, when the Sigmaringen enclave was taken by Free French forces. Pétain was brought back to France, by then under control of the Provisional French Republic, and put on trial for treason.

The clandestine press of the French Resistance was collectively responsible for printing flyers, broadsheets, newspapers, and even books in secret in France during the German occupation of France in the Second World War. The secret press was used to disseminate the ideas of the French Resistance in cooperation with the Free French, and played an important role in the liberation of France and in the history of French journalism, particularly during the 1944 Freedom of the Press Ordinances.

The General Union of French Israelites was a body created by the antisemitic French politician Xavier Vallat under the Vichy regime after the Fall of France in World War II. UGIF was created by decree on 29 November 1941 following a German request, for the express purpose of enabling the discovery and classification of Jews in France and isolating them both morally and materially from the rest of the French population. It operated in two zones: the northern zone, chaired by André Baur, and the southern zone, under the chairmanship of Raymond-Raoul Lambert.

The Law of 3 October 1940 on the status of Jews was a law enacted by Vichy France. It provided a legal definition of the expression Jewish race, which was used during the Nazi occupation for the implementation of Vichy's ideological policy of "National Revolution" comprising corporatist and antisemitic racial policies. It also listed the occupations forbidden to Jews meeting the definition. The law was signed by Marshall Philippe Pétain and the main members of his government.

The Law of 4 October 1940 regarding foreign nationals of the Jewish race was a law enacted by the Vichy regime, which authorized and organized the internment of foreign Jews and marked the beginning of the policy of collaboration of the Vichy regime with Nazi Germany's plans for the extermination of the Jews of Europe. This law was published in the Journal officiel de la République française on 18 October 1940.

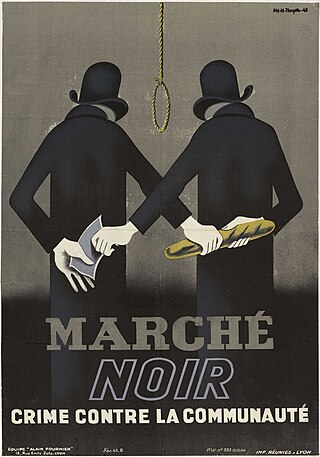

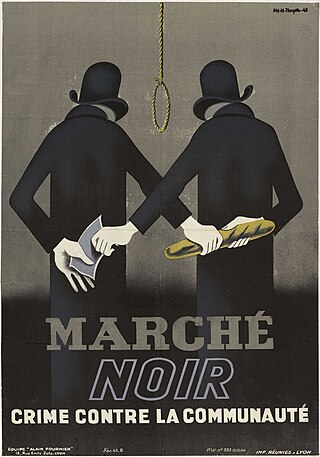

After the defeat of France in 1940, a black market developed in both German-occupied territory and the zone libre controlled by the Vichy regime. Diversions from official channels and clandestine supply chains fed the black market. It came to be seen as "an essential means for survival, as popular resistance to state tyranny invading daily life, as a system for German exploitation, and as a means for unscrupulous producers and dealers to profit from French misery." It involved smugglers, organized crime and other underworld figures, union leaders and corrupt military and police officials. It later became a civil disobedience movement against rationing and attempts to centralize distribution, then eventually evading Nazi food restrictions became a national pastime. Those who could not, such as long-term psychiatric patients, simply did not survive.