Abstraction is a process where general rules and concepts are derived from the use and classifying of specific examples, literal signifiers, first principles, or other methods.

In ontology, the theory of categories concerns itself with the categories of being: the highest genera or kinds of entities. To investigate the categories of being, or simply categories, is to determine the most fundamental and the broadest classes of entities. A distinction between such categories, in making the categories or applying them, is called an ontological distinction. Various systems of categories have been proposed, they often include categories for substances, properties, relations, states of affairs or events. A representative question within the theory of categories might articulate itself, for example, in a query like, "Are universals prior to particulars?"

Charles Sanders Peirce was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss, Peirce was "the most original and versatile of America's philosophers and America's greatest logician". Bertrand Russell wrote "he was one of the most original minds of the later nineteenth century and certainly the greatest American thinker ever".

In mathematics, a finitary relation over a sequence of sets X1, ..., Xn is a subset of the Cartesian product X1 × ... × Xn; that is, it is a set of n-tuples (x1, ..., xn), each being a sequence of elements xi in the corresponding Xi. Typically, the relation describes a possible connection between the elements of an n-tuple. For example, the relation "x is divisible by y and z" consists of the set of 3-tuples such that when substituted to x, y and z, respectively, make the sentence true.

In Boolean functions and propositional calculus, the Sheffer stroke denotes a logical operation that is equivalent to the negation of the conjunction operation, expressed in ordinary language as "not both". It is also called non-conjunction, or alternative denial, or NAND. In digital electronics, it corresponds to the NAND gate. It is named after Henry Maurice Sheffer and written as or as or as or as in Polish notation by Łukasiewicz.

Truth or verity is the property of being in accord with fact or reality. In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise correspond to it, such as beliefs, propositions, and declarative sentences.

The distinction between subject and object is a basic idea of philosophy.

Classical logic or Frege–Russell logic is the intensively studied and most widely used class of deductive logic. Classical logic has had much influence on analytic philosophy.

Abductive reasoning is a form of logical inference that seeks the simplest and most likely conclusion from a set of observations. It was formulated and advanced by American philosopher and logician Charles Sanders Peirce beginning in the latter half of the 19th century.

In mathematics and logic, a corollary is a theorem of less importance which can be readily deduced from a previous, more notable statement. A corollary could, for instance, be a proposition which is incidentally proved while proving another proposition; it might also be used more casually to refer to something which naturally or incidentally accompanies something else.

"Pragmaticism" is a term used by Charles Sanders Peirce for his pragmatic philosophy starting in 1905, in order to distance himself and it from pragmatism, the original name, which had been used in a manner he did not approve of in the "literary journals". Peirce in 1905 announced his coinage "pragmaticism", saying that it was "ugly enough to be safe from kidnappers". Today, outside of philosophy, "pragmatism" is often taken to refer to a compromise of aims or principles, even a ruthless search for mercenary advantage. Peirce gave other or more specific reasons for the distinction in a surviving draft letter that year and in later writings. Peirce's pragmatism, that is, pragmaticism, differed in Peirce's view from other pragmatisms by its commitments to the spirit of strict logic, the immutability of truth, the reality of infinity, and the difference between (1) actively willing to control thought, to doubt, to weigh reasons, and (2) willing not to exert the will, willing to believe. In his view his pragmatism is, strictly speaking, not itself a whole philosophy, but instead a general method for the clarification of ideas. He first publicly formulated his pragmatism as an aspect of scientific logic along with principles of statistics and modes of inference in his "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" series of articles in 1877-8.

In semiotics, a sign is anything that communicates a meaning that is not the sign itself to the interpreter of the sign. The meaning can be intentional, as when a word is uttered with a specific meaning, or unintentional, as when a symptom is taken as a sign of a particular medical condition. Signs can communicate through any of the senses, visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, or taste.

A pragmatic theory of truth is a theory of truth within the philosophies of pragmatism and pragmaticism. Pragmatic theories of truth were first posited by Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey. The common features of these theories are a reliance on the pragmatic maxim as a means of clarifying the meanings of difficult concepts such as truth; and an emphasis on the fact that belief, certainty, knowledge, or truth is the result of an inquiry.

An existential graph is a type of diagrammatic or visual notation for logical expressions, created by Charles Sanders Peirce, who wrote on graphical logic as early as 1882, and continued to develop the method until his death in 1914. They include both a separate graphical notation for logical statements and a logical calculus, a formal system of rules of inference that can be used to derive theorems.

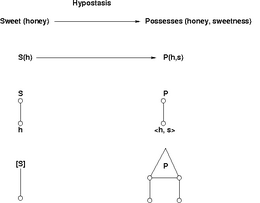

Continuous predicate is a term coined by Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) to describe a special type of relational predicate that results as the limit of a recursive process of hypostatic abstraction.

In philosophical logic, a slingshot argument is one of a group of arguments claiming to show that all true sentences stand for the same thing.

In logic, the monadic predicate calculus is the fragment of first-order logic in which all relation symbols in the signature are monadic, and there are no function symbols. All atomic formulas are thus of the form , where is a relation symbol and is a variable.

Charles Sanders Peirce began writing on semiotics, which he also called semeiotics, meaning the philosophical study of signs, in the 1860s, around the time that he devised his system of three categories. During the 20th century, the term "semiotics" was adopted to cover all tendencies of sign researches, including Ferdinand de Saussure's semiology, which began in linguistics as a completely separate tradition.

On May 14, 1867, the 27–year-old Charles Sanders Peirce, who eventually founded pragmatism, presented a paper entitled "On a New List of Categories" to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Among other things, this paper outlined a theory of predication involving three universal categories that Peirce continued to apply in philosophy and elsewhere for the rest of his life. The categories demonstrate and concentrate the pattern seen in "How to Make Our Ideas Clear", and other three-way distinctions in Peirce's work.

In logic, a quantifier is an operator that specifies how many individuals in the domain of discourse satisfy an open formula. For instance, the universal quantifier in the first order formula expresses that everything in the domain satisfies the property denoted by . On the other hand, the existential quantifier in the formula expresses that there exists something in the domain which satisfies that property. A formula where a quantifier takes widest scope is called a quantified formula. A quantified formula must contain a bound variable and a subformula specifying a property of the referent of that variable.