In logic, the law of excluded middle or the principle of excluded middle states that for every proposition, either this proposition or its negation is true. It is one of the three laws of thought, along with the law of noncontradiction, and the law of identity; however, no system of logic is built on just these laws, and none of these laws provides inference rules, such as modus ponens or De Morgan's laws. The law is also known as the law / principleof the excluded third, in Latin principium tertii exclusi. Another Latin designation for this law is tertium non datur or "no third [possibility] is given". In classical logic, the law is a tautology.

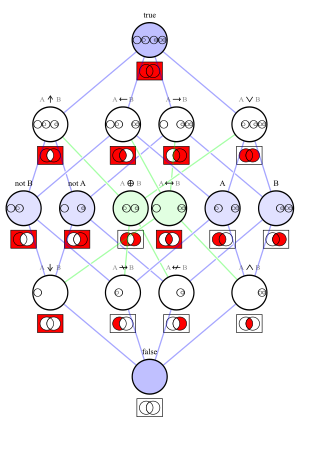

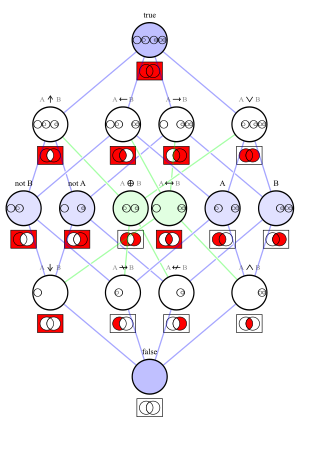

In logic, a logical connective is a logical constant. Connectives can be used to connect logical formulas. For instance in the syntax of propositional logic, the binary connective can be used to join the two atomic formulas and , rendering the complex formula .

The propositional calculus is a branch of logic. It is also called propositional logic, statement logic, sentential calculus, sentential logic, or sometimes zeroth-order logic. Sometimes, it is called first-order propositional logic to contrast it with System F, but it should not be confused with first-order logic. It deals with propositions and relations between propositions, including the construction of arguments based on them. Compound propositions are formed by connecting propositions by logical connectives representing the truth functions of conjunction, disjunction, implication, biconditional, and negation. Some sources include other connectives, as in the table below.

In propositional logic and Boolean algebra, De Morgan's laws, also known as De Morgan's theorem, are a pair of transformation rules that are both valid rules of inference. They are named after Augustus De Morgan, a 19th-century British mathematician. The rules allow the expression of conjunctions and disjunctions purely in terms of each other via negation.

In Boolean logic, a formula is in conjunctive normal form (CNF) or clausal normal form if it is a conjunction of one or more clauses, where a clause is a disjunction of literals; otherwise put, it is a product of sums or an AND of ORs.

Intuitionistic logic, sometimes more generally called constructive logic, refers to systems of symbolic logic that differ from the systems used for classical logic by more closely mirroring the notion of constructive proof. In particular, systems of intuitionistic logic do not assume the law of the excluded middle and double negation elimination, which are fundamental inference rules in classical logic.

In Boolean logic, logical NOR, non-disjunction, or joint denial is a truth-functional operator which produces a result that is the negation of logical or. That is, a sentence of the form (p NOR q) is true precisely when neither p nor q is true—i.e. when both p and q are false. It is logically equivalent to and , where the symbol signifies logical negation, signifies OR, and signifies AND.

In logic and mathematics, the logical biconditional, also known as material biconditional or equivalence or biimplication or bientailment, is the logical connective used to conjoin two statements and to form the statement " if and only if ", where is known as the antecedent, and the consequent.

Paraconsistent logic is a type of non-classical logic that allows for the coexistence of contradictory statements without leading to a logical explosion where anything can be proven true. Specifically, paraconsistent logic is the subfield of logic that is concerned with studying and developing "inconsistency-tolerant" systems of logic, purposefully excluding the principle of explosion.

Dialetheism is the view that there are statements that are both true and false. More precisely, it is the belief that there can be a true statement whose negation is also true. Such statements are called "true contradictions", dialetheia, or nondualisms.

In logic, a truth function is a function that accepts truth values as input and produces a unique truth value as output. In other words: the input and output of a truth function are all truth values; a truth function will always output exactly one truth value, and inputting the same truth value(s) will always output the same truth value. The typical example is in propositional logic, wherein a compound statement is constructed using individual statements connected by logical connectives; if the truth value of the compound statement is entirely determined by the truth value(s) of the constituent statement(s), the compound statement is called a truth function, and any logical connectives used are said to be truth functional.

The material conditional is an operation commonly used in logic. When the conditional symbol is interpreted as material implication, a formula is true unless is true and is false. Material implication can also be characterized inferentially by modus ponens, modus tollens, conditional proof, and classical reductio ad absurdum.

In mathematical logic, Heyting arithmetic is an axiomatization of arithmetic in accordance with the philosophy of intuitionism. It is named after Arend Heyting, who first proposed it.

In mathematics, a set is inhabited if there exists an element .

Consequentia mirabilis, also known as Clavius's Law, is used in traditional and classical logic to establish the truth of a proposition from the inconsistency of its negation. It is thus related to reductio ad absurdum, but it can prove a proposition using just its own negation and the concept of consistency. For a more concrete formulation, it states that if a proposition is a consequence of its negation, then it is true, for consistency. In formal notation:

In logic and mathematics, contraposition, or transposition, refers to the inference of going from a conditional statement into its logically equivalent contrapositive, and an associated proof method known as § Proof by contrapositive. The contrapositive of a statement has its antecedent and consequent inverted and flipped.

In mathematics and philosophy, Łukasiewicz logic is a non-classical, many-valued logic. It was originally defined in the early 20th century by Jan Łukasiewicz as a three-valued modal logic; it was later generalized to n-valued as well as infinitely-many-valued (ℵ0-valued) variants, both propositional and first order. The ℵ0-valued version was published in 1930 by Łukasiewicz and Alfred Tarski; consequently it is sometimes called the Łukasiewicz–Tarski logic. It belongs to the classes of t-norm fuzzy logics and substructural logics.

Minimal logic, or minimal calculus, is a symbolic logic system originally developed by Ingebrigt Johansson. It is an intuitionistic and paraconsistent logic, that rejects both the law of the excluded middle as well as the principle of explosion, and therefore holding neither of the following two derivations as valid:

In logic, philosophy, and theoretical computer science, dynamic logic is an extension of modal logic capable of encoding properties of computer programs.

In logic, Peirce's law is named after the philosopher and logician Charles Sanders Peirce. It was taken as an axiom in his first axiomatisation of propositional logic. It can be thought of as the law of excluded middle written in a form that involves only one sort of connective, namely implication.