The principal inverses are listed in the following table.

Domains

If x is allowed to be a complex number, then the range of y applies only to its real part.

The table below displays names and domains of the inverse trigonometric functions along with the range of their usual principal values in radians.

Name

| Symbol | | Domain | | Image/Range | Inverse

function | | Domain | | Image of

principal values |

|---|

| sine |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| cosine |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| tangent |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

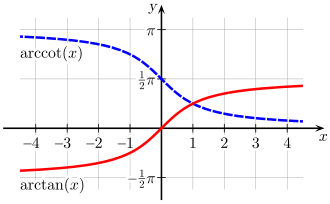

| cotangent |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| secant |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| cosecant |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

The symbol  denotes the set of all real numbers and

denotes the set of all real numbers and  denotes the set of all integers. The set of all integer multiples of

denotes the set of all integers. The set of all integer multiples of  is denoted by

is denoted by

The symbol  denotes set subtraction so that, for instance,

denotes set subtraction so that, for instance,  is the set of points in

is the set of points in  (that is, real numbers) that are not in the interval

(that is, real numbers) that are not in the interval

The Minkowski sum notation  and

and  that is used above to concisely write the domains of

that is used above to concisely write the domains of  is now explained.

is now explained.

Domain of cotangent  and cosecant

and cosecant  : The domains of

: The domains of  and

and  are the same. They are the set of all angles

are the same. They are the set of all angles  at which

at which  i.e. all real numbers that are not of the form

i.e. all real numbers that are not of the form  for some integer

for some integer

Domain of tangent  and secant

and secant  : The domains of

: The domains of  and

and  are the same. They are the set of all angles

are the same. They are the set of all angles  at which

at which