Madera County, officially the County of Madera, is a county located at the geographic center of the U.S. state of California. It features a varied landscape, encompassing the eastern San Joaquin Valley and the central Sierra Nevada, with Madera serving as the county seat. Established in 1893 from part of Fresno County, Madera County reported a population of 156,255 in the 2020 census.

Hume Lake is a reservoir in the Sierra Nevada, within Sequoia National Forest and Fresno County, central California.

Nelder Grove, located in the western Sierra Nevada within the Sierra National Forest in Madera County, California, is a Giant sequoia grove that was formerly known as Fresno Grove. The grove is a 1,540-acre (6.2 km2) tract containing 60 mature Giant Sequoia trees, the largest concentration of giant sequoias in the Sierra National Forest. The grove also contains several historical points of interest, including pioneer cabins, giant sequoia stumps left by 19th-century loggers, and the site where the Forest King exhibition tree was felled in 1870 for display.

The California Western Railroad, AKA Mendocino Railway, popularly called the Skunk Train, is a rail freight and heritage railroad transport railway in Mendocino County, California, United States, running from the railroad's headquarters in the coastal town of Fort Bragg to the interchange with the Northwestern Pacific Railroad at Willits.

North Fork is an unincorporated community in Madera County, California, United States. As of the 2020 United States census it had a population of 3,250. For statistical purposes, the United States Census Bureau has defined North Fork as a census-designated place (CDP). North Fork is part of the Madera Metropolitan Statistical Area and is home to the tribal headquarters of the Northfork Rancheria of Mono Indians of California.

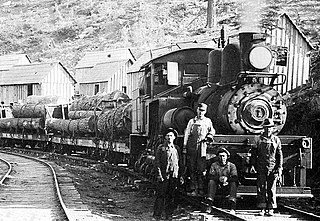

The Yosemite Mountain Sugar Pine Railroad (YMSPRR) is a historic 3 ft narrow gauge railway with two operating steam locomotives located near Fish Camp, California, in the Sierra National Forest near the southern entrance to Yosemite National Park. Rudy Stauffer organized the YMSPRR in 1961, utilizing historic railroad track, rolling stock and locomotives to construct a tourist line along the historic route of the Madera Sugar Pine Lumber Company.

Converse Basin Grove is a grove of giant sequoia trees in the Giant Sequoia National Monument in the Sierra Nevada, in Fresno County, California, 5 miles (8 km) north of General Grant Grove, just outside Kings Canyon National Park. Once home to the largest population of giant sequoias in the world, covering 4,600 acres (19 km2) acres, the grove was extensively logged by the Sanger Lumber Company at the turn of the 20th century. The clearcutting of 8,000 giant sequoias, many of which were over 2,000 years old, resulted in the destruction of the old-growth forest ecosystem.

The Minarets and Western Railway was a Class II common carrier that operated in Fresno County, California, from 1921 to 1933. The railway was owned by the Sugar Pine Lumber Company and was built the same year the lumber company was incorporated so that it could haul timber from the forest near Minarets to its sawmill at Pinedale. The southern portion of the line was operated with joint trackage rights with Southern Pacific.

Central Camp is an unincorporated community in Madera County, California. It is located 3 miles (4.8 km) west of Shuteye Peak, at an elevation of 5417 feet.

The Caspar, South Fork & Eastern Railroad provided transportation for the Caspar Lumber Company in Mendocino County, California. The railroad operated the first steam locomotive on the coast of Mendocino County in 1875. Caspar Lumber Company lands became Jackson Demonstration State Forest in 1955, named for Caspar Lumber Company founder, Jacob Green Jackson.

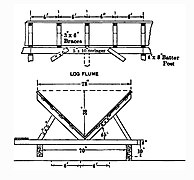

The Hume-Bennett Lumber Company was a logging operation in the Sequoia National Forest in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The company and its predecessors were known for building the world's longest log flume and the first multiple-arch hydroelectric dam. However, the company also engaged in destructive clearcutting logging practices, cutting down 8,000 giant sequoias in Converse Basin in a decade-long event that has been described as "the greatest orgy of destructive lumbering in the history of the world."

The Carson and Tahoe Lumber and Fluming Company (C&TL&F) was formed to move lumber from trees growing along the shore of Lake Tahoe to the silver mines of the Comstock Lode. Between 1872 and 1898 C&TL&F transferred 750 million board foot of lumber logged from 80,000 acres (32,000 ha) of virgin timberland.

The Michigan-California Lumber Company was an early 20th-century Ponderosa and Sugar pine logging operation in the Sierra Nevada. It is best remembered for the Shay locomotives used to move logs to the sawmill.

The Madera Sugar Pine Company was a United States lumber company that operated in the Sierra Nevada region of California during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The company distinguished itself through the use of innovative technologies, including the southern Sierra's first log flume and logging railroad, along with the early adoption of the Steam Donkey engine. Its significant regional impact led to the establishment of towns such as Madera, Fish Camp, and Sugar Pine, as well as the growth of Fresno Flats and the formation of Madera County.

The Sugar Pine Lumber Company was an early 20th century logging operation and railroad in the Sierra Nevada. Unable to secure water rights to build a log flume, the company operated the “crookedest railroad ever built." They later developed the Minarets-type locomotive, the largest and most powerful saddle tank locomotive ever made. The company was also a pioneer in the electrification of logging where newly plentiful hydroelectric power replaced the widespread use of steam engines.

The Yosemite Lumber Company was an early 20th century Sugar Pine and White Pine logging operation in the Sierra Nevada. The company built the steepest logging incline ever, a 3,100 feet (940 m) route that tied the high-country timber tracts in Yosemite National Park to the low-lying Yosemite Valley Railroad running alongside the Merced River. From there, the logs went by rail to the company’s sawmill at Merced Falls, about fifty-four miles west of El Portal.

Charles Porter Converse was a mid-19th century Californian businessman who was the director of the Kings River Lumber Company and the namesake of Converse Basin Grove. He was involved in various controversies and legal issues during his lifetime and died by drowning in San Francisco Bay.

Millwood was a lumber boomtown located in present-day Sequoia National Forest near Converse Basin Grove in California. It was established in 1891 by the Kings River Lumber Company and was connected to the Sequoia Railroad, which brought logs to the town to be turned into rough lumber. The lumber was then transported by log flume to Sanger, a journey of 54 miles. At its peak, Millwood had a population of over 2,000 people and featured two hotels, a summer school, and a post office. However, today there are no remaining structures or buildings at the Millwood site.

The Fresno Flume and Irrigation Company was established in 1891 as a logging and water transportation company in California. A 45-mile cedar flume was built to transport lumber from Shaver Lake to the finishing mill in Clovis. The company changed its name to the Fresno Flume and Lumber Company in 1908, and over the course of its 21-year lifespan, cut an average of 25 million board feet of lumber each year. However, in 1912, the company was sold and ceased all operations after a storm destroyed 2 miles (3.2 km) of the flume. In 1919, Southern California Edison Company bought most of the Shaver property for the Big Creek Hydroelectric Project.

The following is a timeline of the history of the Sierra National Forest in Central California, United States.