Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that established the principle of judicial review, meaning that American courts have the power to strike down laws and statutes they find to violate the Constitution of the United States. Decided in 1803, Marbury is regarded as the single most important decision in American constitutional law. It established that the U.S. Constitution is actual law, not just a statement of political principles and ideals. It also helped define the boundary between the constitutionally separate executive and judicial branches of the federal government.

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congress. Article Three empowers the courts to handle cases or controversies arising under federal law, as well as other enumerated areas. Article Three also defines treason.

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, and therefore they could not enjoy the rights and privileges the Constitution conferred upon American citizens. The decision is widely considered the worst in the Supreme Court's history, being widely denounced for its overt racism, judicial activism, poor legal reasoning, and crucial role in the start of the American Civil War four years later. Legal scholar Bernard Schwartz said that it "stands first in any list of the worst Supreme Court decisions". A future chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes, called it the Court's "greatest self-inflicted wound".

Philip Pendleton Barbour was the tenth speaker of the United States House of Representatives and an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He is the only individual to serve in both positions.

The Midnight Judges Act expanded the federal judiciary of the United States. The act was supported by the John Adams administration and the Federalist Party. Passage of the act has been described as "the last major policy achievement of the Federalists."

Stuart v. Laird, 5 U.S. 299 (1803), was a case decided by United States Supreme Court notably a week after its famous decision in Marbury v. Madison.

William Marbury was a highly successful American businessman and one of the "Midnight Judges" appointed by United States President John Adams the day before he left office. He was the plaintiff in the landmark 1803 Supreme Court case Marbury v. Madison.

The Supreme Court of the United States is the only court specifically established by the Constitution of the United States, implemented in 1789; under the Judiciary Act of 1789, the Court was to be composed of six members—though the number of justices has been nine for most of its history, this number is set by Congress, not the Constitution. The court convened for the first time on February 2, 1790.

The Burger Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1969 to 1986, when Warren E. Burger served as Chief Justice of the United States. Burger succeeded Earl Warren as Chief Justice after Warren's retirement, and served as Chief Justice until his retirement, when William Rehnquist was nominated and confirmed as Burger's replacement. The Burger Court is generally considered to be the last liberal court to date. It has been described as a transitional court, due to its transition from having the liberal rulings of the Warren Court to the conservative rulings of the Rehnquist Court.

The Jay Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1789 to 1795, when John Jay served as the first Chief Justice of the United States. Jay served as Chief Justice until his resignation, at which point John Rutledge took office as a recess appointment. The Supreme Court was established in Article III of the United States Constitution, but the workings of the federal court system were largely laid out by the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established a six-member Supreme Court, composed of one Chief Justice and five Associate Justices. As the first President, George Washington was responsible for appointing the entire Supreme Court. The act also created thirteen judicial districts, along with district courts and circuit courts for each district.

The Ellsworth Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1796 to 1800, when Oliver Ellsworth served as the third Chief Justice of the United States. Ellsworth took office after the Senate refused to confirm the nomination of Chief Justice John Rutledge, who briefly served as a Chief Justice as a recess appointment. Ellsworth served as Chief Justice until his resignation, at which point John Marshall took office. With some exceptions, the Ellsworth Court was the last Supreme Court to use seriatim opinions.

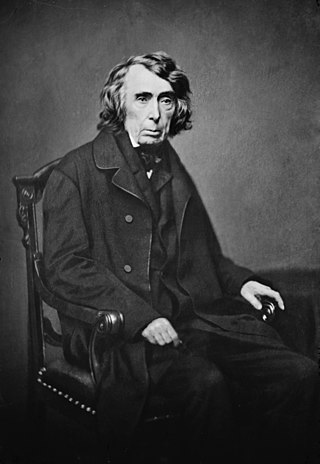

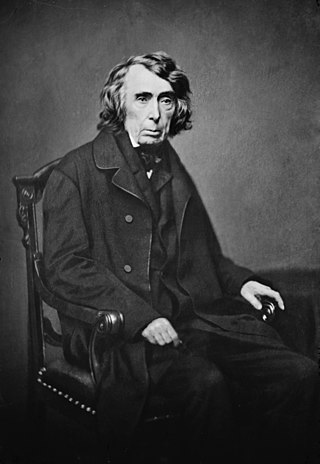

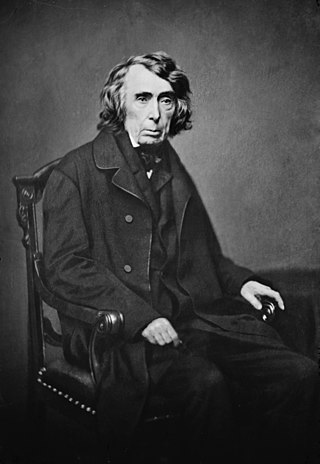

The Taney Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1836 to 1864, when Roger Taney served as the fifth Chief Justice of the United States. Taney succeeded John Marshall as Chief Justice after Marshall's death in 1835. Taney served as Chief Justice until his death in 1864, at which point Salmon P. Chase took office. Taney had been an important member of Andrew Jackson's administration, an advocate of Jacksonian democracy, and had played a major role in the Bank War, during which Taney wrote a memo questioning the Supreme Court's power of judicial review. However, the Taney Court did not strongly break from the decisions and precedents of the Marshall Court, as it continued to uphold a strong federal government with an independent judiciary. Most of the Taney Court's holdings are overshadowed by the decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, in which the court ruled that African-Americans could not be citizens. However, the Taney Court's decisions regarding economic issues and separation of powers set important precedents, and the Taney Court has been lauded for its ability to adapt regulatory law to a country undergoing remarkable technological and economic progress.

The Chase Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1864 to 1873, when Salmon P. Chase served as the sixth Chief Justice of the United States. Chase succeeded Roger Taney as Chief Justice after the latter's death. Appointed by President Abraham Lincoln, Chase served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Morrison Waite was nominated and confirmed as his successor.

John Marshall was an American statesman, lawyer, and Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longest serving justice in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court, and he is widely regarded as one of the most influential justices ever to serve. Prior to joining the court, Marshall briefly served as both the U.S. secretary of state under President John Adams, and a representative, in the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia, thereby making him one of the few Americans to have held a constitutional office in each of the three branches of the United States federal government.

Roger Brooke Taney was an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Taney delivered the majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), ruling that African Americans could not be considered U.S. citizens and that Congress could not prohibit slavery in the U.S. territories. Prior to joining the U.S. Supreme Court, Taney served as the U.S. attorney general and U.S. secretary of the treasury under President Andrew Jackson. He was the first Catholic to serve on the Supreme Court.

United States v. More, 7 U.S. 159 (1805), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that it had no jurisdiction to hear appeals from criminal cases in the circuit courts by writs of error. Relying on the Exceptions Clause, More held that Congress's enumerated grants of appellate jurisdiction to the Court operated as an exercise of Congress's power to eliminate all other forms of appellate jurisdiction.

The Waite Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1874 to 1888, when Morrison Waite served as the seventh Chief Justice of the United States. Waite succeeded Salmon P. Chase as Chief Justice after the latter's death. Waite served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Melville Fuller was nominated and confirmed as Waite's successor.

The Taft Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1921 to 1930, when William Howard Taft served as Chief Justice of the United States. Taft succeeded Edward Douglass White as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and Taft served as Chief Justice until his resignation, at which point Charles Evans Hughes was nominated and confirmed as Taft's replacement. Taft was also the nation's 27th president (1909–13); he is the only person to serve as both President of the United States and Chief Justice.

The White Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1910 to 1921, when Edward Douglass White served as Chief Justice of the United States. White, an associate justice since 1894, succeeded Melville Fuller as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and White served as Chief Justice until his death a decade later. He was the first sitting associate justice to be elevated to chief justice in the Court's history. He was succeeded by former president William Howard Taft.

The Fuller Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1888 to 1910, when Melville Fuller served as the eighth Chief Justice of the United States. Fuller succeeded Morrison R. Waite as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and Fuller served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Associate Justice Edward Douglass White was nominated and confirmed as Fuller's replacement.