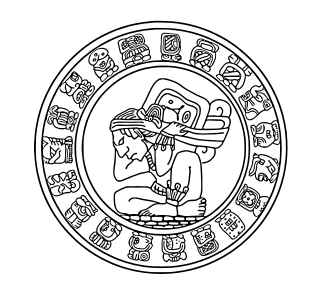

A chacmool is a form of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican sculpture depicting a reclining figure with its head facing 90 degrees from the front, supporting itself on its elbows and supporting a bowl or a disk upon its stomach. These figures possibly symbolised slain warriors carrying offerings to the gods; the bowl upon the chest was used to hold sacrificial offerings, including pulque, tamales, tortillas, tobacco, turkeys, feathers, and incense. In Aztec examples, the receptacle is a cuauhxicalli. Chacmools were often associated with sacrificial stones or thrones. The chacmool form of sculpture first appeared around the 9th century AD in the Valley of Mexico and the northern Yucatán Peninsula.

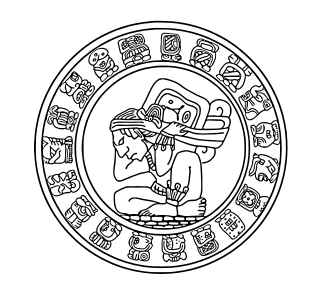

Mictlāntēcutli or Mictlantecuhtli, in Aztec mythology, is a god of the dead and the king of Mictlan (Chicunauhmictlan), the lowest and northernmost section of the underworld. He is one of the principal gods of the Aztecs and is the most prominent of several gods and goddesses of death and the underworld. The worship of Mictlantecuhtli sometimes involved ritual cannibalism, with human flesh being consumed in and around the temple. Other names given to Mictlantecuhtli include Ixpuztec, Nextepehua, and Tzontemoc.

In Aztec mythology, Xiuhtecuhtli, was the god of fire, day and heat. In historical sources he is called by many names, which reflect his varied aspects and dwellings in the three parts of the cosmos. He was the lord of volcanoes, the personification of life after death, warmth in cold (fire), light in darkness and food during famine. He was also named Cuezaltzin ("flame") and Ixcozauhqui, and is sometimes considered to be the same as Huehueteotl, although Xiuhtecuhtli is usually shown as a young deity. His wife was Chalchiuhtlicue. Xiuhtecuhtli is sometimes considered to be a manifestation of Ometecuhtli, the Lord of Duality, and according to the Florentine Codex Xiuhtecuhtli was considered to be the father of the Gods, who dwelled in the turquoise enclosure in the center of earth. Xiuhtecuhtli-Huehueteotl was one of the oldest and most revered of the indigenous pantheon. The cult of the God of Fire, of the Year, and of Turquoise perhaps began as far back as the middle Preclassic period. Turquoise was the symbolic equivalent of fire for Aztec priests. A small fire was permanently kept alive at the sacred center of every Aztec home in honor of Xiuhtecuhtli.

In Aztec mythology, Xipe Totec or Xipetotec was a life-death-rebirth deity, god of agriculture, vegetation, the east, spring, goldsmiths, silversmiths, liberation, deadly warfare, the seasons, and the earth. The female equivalent of Xipe Totec was the goddess Xilonen-Chicomecoatl.

In Aztec religion, Xiuhcōātl was a mythological serpent, regarded as the spirit form of Xiuhtecuhtli, the Aztec fire deity sometimes represented as an atlatl or a weapon wielded by Huitzilopochtli. Xiuhcoatl is a Classical Nahuatl word that translates as "turquoise serpent" and also carries the symbolic and descriptive translation of "fire serpent".

Mesoamerican chronology divides the history of prehispanic Mesoamerica into several periods: the Paleo-Indian ; the Archaic, the Preclassic or Formative (2500 BCE – 250 CE), the Classic (250–900 CE), and the Postclassic (900–1521 CE); as well as the post European contact Colonial Period (1521–1821), and Postcolonial, or the period after independence from Spain (1821–present).

Eduardo Matos Moctezuma is a Mexican archaeologist. From 1978 to 1982 he directed excavations at the Templo Mayor, the remains of a major Aztec pyramid in central Mexico City.

Teopantecuanitlan is an archaeological site in the Mexican state of Guerrero that represents an unexpectedly early development of complex society for the region. The site dates to the Early to Middle Formative Periods, with the archaeological evidence indicating that some kind of connection existed between Teopantecuanitlan and the Olmec heartland of the Gulf Coast. Prior to the discovery of Teopantecuanitlan in the early 1980s, little was known about the region's sociocultural development and organization during the Formative period.

The Temple of the Sun is the largest building in Teotihuacan, and one of the largest in Mesoamerica. It is believed to have been constructed about 200 AD. Found along the Avenue of the Dead, in between the Pyramid of the Moon and the Ciudadela, and in the shadow of the mountain Cerro Gordo, the pyramid is part of a large complex in the heart of the city.

The geography of Mesoamerica describes the geographic features of Mesoamerica, a culture area in the Americas inhabited by complex indigenous pre-Columbian cultures exhibiting a suite of shared and common cultural characteristics. Several well-known Mesoamerican cultures include the Olmec, Teotihuacan, the Maya, the Aztec and the Purépecha. Mesoamerica is often subdivided in a number of ways. One common method, albeit a broad and general classification, is to distinguish between the highlands and lowlands. Another way is to subdivide the region into sub-areas that generally correlate to either culture areas or specific physiographic regions.

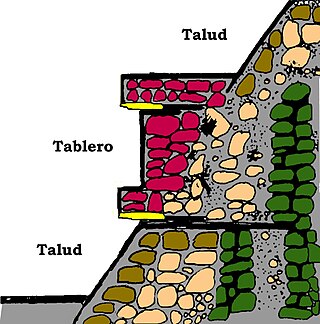

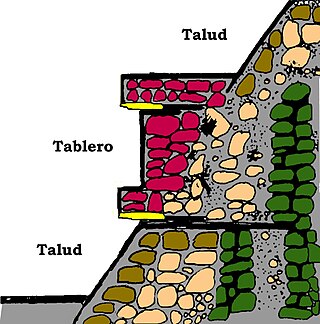

Talud-tablero is an architectural style most commonly used in platforms, temples, and pyramids in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, becoming popular in the Early Classic Period of Teotihuacan. Talud-tablero consists of an inward-sloping surface or panel called the talud, with a panel or structure perpendicular to the ground sitting upon the slope called the tablero. This may also be referred to as the slope-and-panel style.

The Feathered Serpent is a prominent supernatural entity or deity, found in many Mesoamerican religions. It is still called Quetzalcoatl among the Aztecs, Kukulkan among the Yucatec Maya, and Q'uq'umatz and Tohil among the K'iche' Maya.

Pedro Armillas Garcia was Spanish academic anthropologist, archaeologist, and an influential pre-Columbian Mesoamerica scholar of the mid-20th century. As an archaeologist he was known both for his fieldwork and excavations at numerous sites in central and northern Mexico, and his contributions in archaeological theory. His study of how Mesoamerican agriculture and subsistence modes of production influenced the development of Mesoamerican cultures was a pioneering one, and he was one of the earliest to investigate pre-Columbian irrigation and hydraulic systems.

El Tepozteco is an archaeological site in the Mexican state of Morelos. It consists of a small temple to Tepoztēcatl, the Aztec god of the alcoholic beverage pulque.

Xochipala is a minor archaeological site in the Mexican state of Guerrero, whose name has become attached, somewhat erroneously, to a style of Formative Period figurines and pottery from 1500 to 200 BCE. The archaeological site belongs to the Classic and Postclassic eras, approximately 200–1400 CE.

Davíd Lee Carrasco is an American academic historian of religion, anthropologist, and Mesoamericanist scholar. As of 2001, he holds the inaugural appointment as Neil L. Rudenstine Professor of Latin America Studies at the Harvard Divinity School, in a joint appointment with the Faculty of Arts and Sciences' Department of Anthropology at Harvard University. Carrasco previously taught at the University of Colorado, Boulder and Princeton University and is known for his research and publications on Mesoamerican religion and history, his public speaking as well as wider contributions within Latin American studies and Latino/a studies. He has made statements about Latino contributions to US democracy in public dialogues with Cornel West, Toni Morrison, and Samuel P. Huntington. His work is known primarily for his writings on the ways human societies orient themselves with sacred places.

Cuetlajuchitlán is a Mesoamerican archaeological site located 3 kilometers southeast of Paso Morelos, in the northeast of the Mexican state of Guerrero.

Ixcateopan is an archaeological site located in the town and municipality of Ixcateopan de Cuauhtémoc, 36 kilometers from Taxco, in the isolated and rugged mountains of the northern part of the Mexican state of Guerrero.

The use of mirrors in Mesoamerican culture was associated with the idea that they served as portals to a realm that could be seen but not interacted with. Mirrors in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were fashioned from stone and served a number of uses, from the decorative to the divinatory. An ancient tradition among many Mesoamerican cultures was the practice of divination using the surface of a bowl of water as a mirror. At the time of the Spanish conquest this form of divination was still practiced among the Maya, Aztecs and Purépecha. In Mesoamerican art, mirrors are frequently associated with pools of liquid; this liquid was likely to have been water.

Leonardo Náuhmitl López Luján is an archaeologist and one of the leading researchers of pre-Hispanic Central Mexican societies and the history of archaeology in Mexico. He is director of the Templo Mayor Project in Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) since 1991 and son of renowned historian Alfredo López Austin. He is fellow of El Colegio Nacional, the British Academy, the Society of Antiquaries of London, the Real Academia de la Historia in Madrid, the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, and the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in Paris.