Muisca Confederation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 800 [1] –1540 | |||||||||

Flag of the Muisca Confederation | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Bacatá (Bogotá), Hunza, and Suamox, Tundama (800–1540) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Muysccubun | ||||||||

| Religion | Muisca religion | ||||||||

| Zaque and zipa | |||||||||

• ~1450–1470 | zaque Hunzahúa zipa Meicuchuca | ||||||||

• 1470–1490 | zaque Saguamanchica zipa Michuá | ||||||||

• 1490–1537 1490–1514 | zaque Quemuenchatocha zipa Nemequene | ||||||||

• 1514–1537 | zipa Tisquesusa | ||||||||

• 1537–1540 1537–1539 | zaque Aquiminzaque zipa Sagipa | ||||||||

| Historical era | Pre-Columbian | ||||||||

• Established | c. 800 [1] | ||||||||

| March 1537 | |||||||||

| 20 April 1537 | |||||||||

• Conquest of Hunza | 20 August 1537 | ||||||||

• Destruction of the Sun Temple | September 1537 | ||||||||

| 6 August 1538 20 August 1538 | |||||||||

| 6 August 1539 December 1539 | |||||||||

| 1540 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

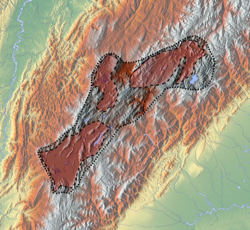

| 1537 | 46,972 km2 (18,136 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• Early 16th century [2] | 2 million | ||||||||

• Density | 42.58/km2 (110.3/sq mi) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

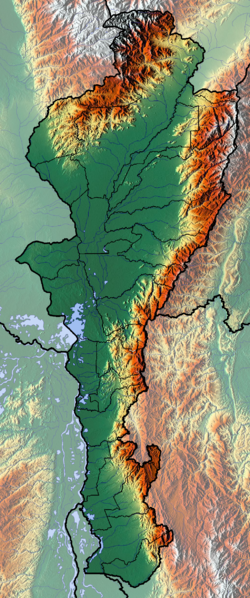

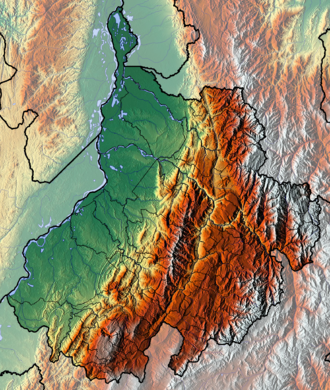

| Today part of | Colombia - Cundinamarca - Boyacá - Santander | ||||||||

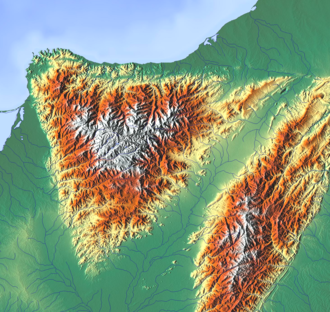

The Muisca Confederation was a loose confederation of different Muisca rulers ( zaques , zipas , iraca , and tundama ) in the central Andean highlands of what is today Colombia before the Spanish conquest of northern South America. The area, presently called Altiplano Cundiboyacense, comprised the current departments of Boyacá, Cundinamarca and minor parts of Santander.

Contents

- Geography

- Climate

- Muisca Confederation

- History

- Territorial organization

- Bacatá

- Chipazaque

- Hunza

- Iraca

- Tundama

- Independent caciques

- Neighbouring indigenous groups

- Sacred sites

- Other sacred sites

- Spanish conquests

- Conquest and early colonial period

- Early colonial period

- See also

- Notes

- References

- Bibliography and further reading

- Spanish chroniclers

According to some Muisca scholars the Muisca Confederation was one of the best-organized confederations of tribes on the South American continent. [3] Other historians and anthropologists, however, such as Jorge Gamboa Mendoza, attribute the present-day knowledge about the confederation and its organization more to a reflection by Spanish chroniclers who predominantly wrote about it a century or more after the Muisca were conquered and proposed the idea of a loose collection of different people with slightly different languages and backgrounds. [4]