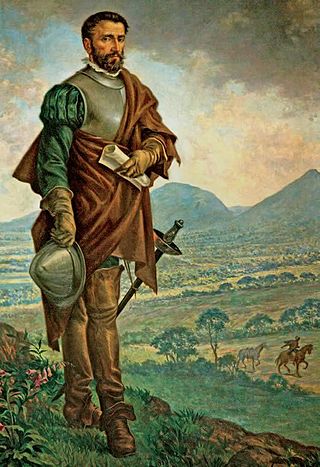

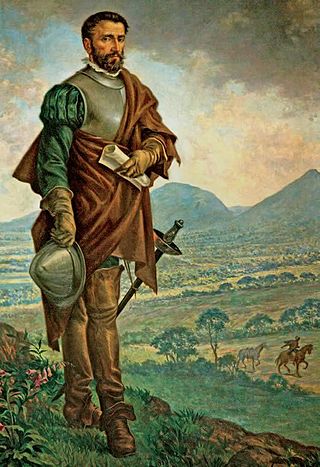

Knowledge of Muisca mythology has come from Muisca scholars Javier Ocampo López, Pedro Simón, Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita, Juan de Castellanos and conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada who was the European making first contact with the Muisca in the 1530s.

Cuchavira or Cuchaviva is the rainbow deity, protector of working women and the sick in the religion of the Muisca. The Muisca and their confederation were one of the advanced civilizations of the Americas and in the fertile intermontane valley that forms the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Andes rain and sun were both very important for their agriculture. Moreover, in those days the Bogotá savanna consisted of various swamps and floodings were regular.

Chaquén was the god of sports and fertility in the religion of the Muisca. The Muisca and their confederation were one of the four advanced civilizations of the Americas and as they were warriors, sports was very important to train the fighters for wars, mainly fought between the zipazgo and the zacazgo but also against other indigenous peoples as the Panches, Muzos and others. When the Spanish arrived in the highlands of central Colombia, the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, they encountered resistance of the guecha warriors, trained by Chaquén.

Huitaca or Xubchasgagua was a rebelling goddess in the religion of the Muisca. The Muisca and their confederation were a civilization who inhabited the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Andes. Huitaca has been described by the chroniclers Juan de Castellanos in his Elegías de varones ilustres de Indias, Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita and Pedro Simón.

Chiminigagua, Chiminichagua or Chimichagua was the supreme being, omnipotent god and creator of the world in the religion of the Muisca. The Muisca and their confederation were one of the four advanced civilizations of the Americas and developed their own religion on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Andes.

Sué, Xué, Sua, Zuhe or Suhé was the god of the Sun in the religion of the Muisca. He was married to Moon goddess Chía. The Muisca and their confederation were one of the four advanced civilizations of the Americas and developed their own religion on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Andes. Both the Sun and rain, impersonated by Chibchacum, were very important for their agriculture.

Goranchacha was a mythical cacique who was said to have been the prophet of the Muisca of South America, in particular of the zacazgo of the northern Muisca Confederation. He is considered the son of the Sun, impersonated by the Sun god Sué.

Muisca religion describes the religion of the Muisca who inhabited the central highlands of the Colombian Andes before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca. The Muisca formed a confederation of holy rulers and had a variety of deities, temples and rituals incorporated in their culture. Supreme being of the Muisca was Chiminigagua who created light and the Earth. He was not directly honoured, yet that was done through Chía, goddess of the Moon, and her husband Sué, god of the Sun. The representation of the two main celestial bodies as husband and wife showed the complementary character of man and woman and the sacred status of marriage.

The Sun Temple of Sogamoso was a temple constructed by the Muisca as a place of worship for their Sun god Sué. The temple was built in Sogamoso, Colombia, then part of the Muisca Confederation and called Sugamuxi. It was the most important temple in the religion of the Muisca. The temple was destroyed by fire brought by the Spanish conquistadores led by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada who was eager to find the legendary El Dorado. A reconstruction has been built in the Archeology Museum of Sogamoso.

Muisca music describes the use of music by the Muisca. The Muisca were organized in the Muisca Confederation before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca of the central highlands of present-day Colombia. The Muisca used music in their religious rituals, to welcome the new cacique and during harvest, sowing and the construction of the houses.

The iraca, sometimes spelled iraka, was the ruler and high priest of Sugamuxi in the confederation of the Muisca who inhabited the Altiplano Cundiboyacense; the central highlands of the Colombian Andes. Iraca can also refer to the Iraka Valley over which they ruled. Important scholars who wrote about the iraca were Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita, Alexander von Humboldt and Ezequiel Uricoechea.

The Moon Temple of Chía was a temple constructed by the Muisca as a place of worship for their Moon goddess Chía. The temple was built in Chía, Cundinamarca, Colombia, then part of the Muisca Confederation. It was one of the most important temples in the religion of the Muisca. The temple was destroyed during the Spanish conquest of the Muisca on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. Little is known about the temple built on the Tíquiza Hill in western Chía bordering Tabio.

The Hunzahúa Well is an archeological site of the Muisca located in the city of Tunja, Boyacá, which in the time of the Muisca Confederation was called Hunza. The well is named after the first zaque of Hunza, Hunzahúa. The well was called Pozo de Donato for a while, after 17th century Jerónimo Donato de Rojas. The well is located on the campus of the Pedagogical and Technological University of Colombia in Tunja. Scholar Javier Ocampo López has written about the well and its mythology. Knowledge about the well has been provided by scholar Pedro Simón.

The Muisca agriculture describes the agriculture of the Muisca, the advanced civilisation that was present in the times before the Spanish conquest on the high plateau in the Colombian Andes; the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. The Muisca were a predominantly agricultural society with small-scale farmfields, part of more extensive terrains. To diversify their diet, they traded mantles, gold, emeralds and salt for fruits, vegetables, coca, yopo and cotton cultivated in lower altitude warmer terrains populated by their neighbours, the Muzo, Panche, Guane, Guayupe, Lache, Sutagao and U'wa. Trade of products grown farther away happened with the Calima, Pijao and Caribbean coastal communities around the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

This article describes the astronomy of the Muisca. The Muisca, one of the four advanced civilisations in the Americas before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca, had a thorough understanding of astronomy, as evidenced by their architecture and calendar, important in their agriculture.

This article describes the role of women in Muisca society. The Muisca were the original inhabitants of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense before the Spanish conquest in the first half of the 16th century. Their society was one of the four great civilizations of the Americas.

This article describes the economy of the Muisca. The Muisca were the original inhabitants of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, the high plateau in the Eastern Ranges of central present-day Colombia. Their rich economy and advanced merchant abilities were widely known by the indigenous groups of the area and described by the Spanish conquistadores whose primary objective was the acquisition of the mineral resources of Tierra Firme; gold, emeralds, carbon, silver and copper.

The Goranchacha Temple is an archeological site of the Muisca located in the city of Tunja, Boyacá, which in the time of the Muisca Confederation was called Hunza. The temple is named after the mythological Goranchacha. The remains of the temple are located on the terrain of the Pedagogical and Technological University of Colombia in Tunja. Scholar Javier Ocampo López has written about the temple and its religious meaning. Knowledge about the temple has been provided by chronicler Pedro Simón.

The Spanish conquest of the Muisca took place from 1537 to 1540. The Muisca were the inhabitants of the central Andean highlands of Colombia before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors. They were organised in a loose confederation of different rulers; the psihipqua of Muyquytá, with his headquarters in Funza, the hoa of Hunza, the iraca of the sacred City of the Sun Sugamuxi, the Tundama of Tundama, and several other independent caciques. The most important rulers at the time of the conquest were psihipqua Tisquesusa, hoa Eucaneme, iraca Sugamuxi and Tundama in the northernmost portion of their territories. The Muisca were organised in small communities of circular enclosures, with a central square where the bohío of the cacique was located. They were called "Salt People" because of their extraction of salt in various locations throughout their territories, mainly in Zipaquirá, Nemocón, and Tausa. For the main part self-sufficient in their well-organised economy, the Muisca traded with the European conquistadors valuable products as gold, tumbaga, and emeralds with their neighbouring indigenous groups. In the Tenza Valley, to the east of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense where the majority of the Muisca lived, they extracted emeralds in Chivor and Somondoco. The economy of the Muisca was rooted in their agriculture with main products maize, yuca, potatoes, and various other cultivations elaborated on elevated fields. Agriculture had started around 3000 BCE on the Altiplano, following the preceramic Herrera Period and a long epoch of hunter-gatherers since the late Pleistocene. The earliest archaeological evidence of inhabitation in Colombia, and one of the oldest in South America, has been found in El Abra, dating to around 12,500 years BP.

This article describes the art produced by the Muisca. The Muisca established one of the four grand civilisations of the pre-Columbian Americas on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in present-day central Colombia. Their various forms of art have been described in detail and include pottery, textiles, body art, hieroglyphs and rock art. While their architecture was modest compared to the Inca, Aztec and Maya civilisations, the Muisca are best known for their skilled goldworking. The Museo del Oro in the Colombian capital Bogotá houses the biggest collection of golden objects in the world, from various Colombian cultures including the Muisca.