The Muisca are an indigenous people and culture of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, Colombia, that formed the Muisca Confederation before the Spanish conquest. The people spoke Muysccubun, a language of the Chibchan language family, also called Muysca and Mosca. They were encountered by conquistadors dispatched by the Spanish Empire in 1537 at the time of the conquest.

The Museum of Gold is an archaeology museum located in Bogotá, Colombia. It is one of the most visited touristic highlights in the country. The museum receives around 500,000 tourists per year.

Bosa is the 7th locality of the Capital District of the Colombian capital, Bogotá. Bosa is located in the southwest of Bogotá and is the 8th largest locality and 9th most populated. This district is inhabited by working-class residents.

A Poporo is a device used by indigenous cultures in present and pre-Columbian South America for storage of small amounts of lime produced from burnt and crushed sea-shells. It consists of two pieces: the receptacle and the lid, which includes a pin that is used to carry the lime to the mouth while a person is chewing coca leaves. Since the chewing of coca is sacred for the indigenous people, the poporos are also believed to have mystical powers and social status.

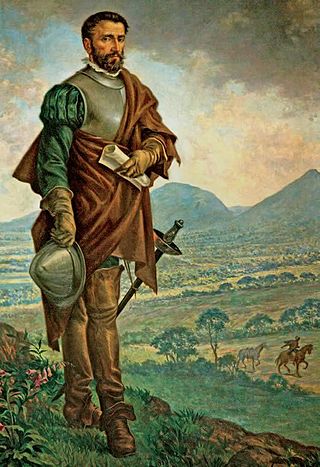

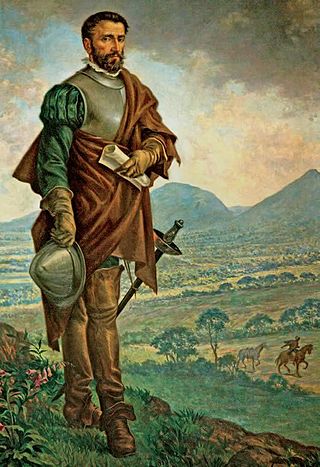

The Spanish conquest of New Granada refers to the conquest by the Spanish monarchy of the Chibcha language-speaking nations of modern-day Colombia and Panama, mainly the Muisca and Tairona that inhabited present-day Colombia, beginning the Spanish colonization of the Americas. It is estimated that around 5 to 8 million people died as a result of Spanish Conquest, either by disease or direct conflict, this is roughly around 80-90% of the Pre-Columbian population of Colombia.

Bacatá is the name given to the main settlement of the Muisca Confederation on the Bogotá savanna. It mostly refers to an area, rather than an individual village, although the name is also found in texts referring to the modern settlement of Funza, in the centre of the savanna. Bacatá was the main seat of the zipa, the ruler of the Bogotá savanna and adjacent areas. The name of the Colombian capital, Bogotá, is derived from Bacatá, but founded as Santafe de Bogotá in the western foothills of the Eastern Hills in a different location than the original settlement Bacatá, west of the Bogotá River, eventually named after Bacatá as well.

The Muisca raft, sometimes referred to as the Golden Raft of El Dorado, is a pre-Columbian votive piece created by the Muisca, an indigenous people of Colombia in the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes. The piece probably refers to the gold offering ceremony described in the legend of El Dorado, which occasionally took place at Lake Guatavita. In this ritual, the new chief (zipa), who was aboard a raft and covered with gold dust, tossed gold objects into the lake as offerings to the gods, before immersing himself into the lake. The figure was created between 1295 and 1410 AD by lost-wax casting in an alloy of gold with silver and copper. The raft was part of an offering that was placed in a cave in the municipality of Pasca. Since its discovery in 1969, the Muisca raft has become a national emblem for Colombia and has been depicted on postage stamps. The piece is exhibited at the Gold Museum in Bogotá.

The Muisca Confederation was a loose confederation of different Muisca rulers in the central Andean highlands of what is today Colombia before the Spanish conquest of northern South America. The area, presently called Altiplano Cundiboyacense, comprised the current departments of Boyacá, Cundinamarca and minor parts of Santander.

Muisca religion describes the religion of the Muisca who inhabited the central highlands of the Colombian Andes before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca. The Muisca formed a confederation of holy rulers and had a variety of deities, temples and rituals incorporated in their culture. Supreme being of the Muisca was Chiminigagua who created light and the Earth. He was not directly honoured, yet that was done through Chía, goddess of the Moon, and her husband Sué, god of the Sun. The representation of the two main celestial bodies as husband and wife showed the complementary character of man and woman and the sacred status of marriage.

Muisca music describes the use of music by the Muisca. The Muisca were organized in the Muisca Confederation before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca of the central highlands of present-day Colombia. The Muisca used music in their religious rituals, to welcome the new cacique and during harvest, sowing and the construction of the houses.

The Muisca agriculture describes the agriculture of the Muisca, the advanced civilisation that was present in the times before the Spanish conquest on the high plateau in the Colombian Andes; the Altiplano Cundiboyacense. The Muisca were a predominantly agricultural society with small-scale farmfields, part of more extensive terrains. To diversify their diet, they traded mantles, gold, emeralds and salt for fruits, vegetables, coca, yopo and cotton cultivated in lower altitude warmer terrains populated by their neighbours, the Muzo, Panche, Guane, Guayupe, Lache, Sutagao and U'wa. Trade of products grown farther away happened with the Calima, Pijao and Caribbean coastal communities around the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.

This article describes the astronomy of the Muisca. The Muisca, one of the four advanced civilisations in the Americas before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca, had a thorough understanding of astronomy, as evidenced by their architecture and calendar, important in their agriculture.

The Muisca inhabited the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Colombian Andes before the arrival of the Spanish and were an advanced civilisation. They mummified the higher social class members of their society, mainly the zipas, zaques, caciques, priests and their families. The mummies would be placed in caves or in dedicated houses ("mausoleums") and were not buried.

This article describes the economy of the Muisca. The Muisca were the original inhabitants of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, the high plateau in the Eastern Ranges of central present-day Colombia. Their rich economy and advanced merchant abilities were widely known by the indigenous groups of the area and described by the Spanish conquistadores whose primary objective was the acquisition of the mineral resources of Tierra Firme; gold, emeralds, carbon, silver and copper.

The Spanish conquest of the Muisca took place from 1537 to 1540. The Muisca were the inhabitants of the central Andean highlands of Colombia before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors. They were organised in a loose confederation of different rulers; the psihipqua of Muyquytá, with his headquarters in Funza, the hoa of Hunza, the iraca of the sacred City of the Sun Sugamuxi, the Tundama of Tundama, and several other independent caciques. The most important rulers at the time of the conquest were psihipqua Tisquesusa, hoa Eucaneme, iraca Sugamuxi and Tundama in the northernmost portion of their territories. The Muisca were organised in small communities of circular enclosures, with a central square where the bohío of the cacique was located. They were called "Salt People" because of their extraction of salt in various locations throughout their territories, mainly in Zipaquirá, Nemocón, and Tausa. For the main part self-sufficient in their well-organised economy, the Muisca traded with the European conquistadors valuable products as gold, tumbaga, and emeralds with their neighbouring indigenous groups. In the Tenza Valley, to the east of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense where the majority of the Muisca lived, they extracted emeralds in Chivor and Somondoco. The economy of the Muisca was rooted in their agriculture with main products maize, yuca, potatoes, and various other cultivations elaborated on elevated fields. Agriculture had started around 3000 BCE on the Altiplano, following the preceramic Herrera Period and a long epoch of hunter-gatherers since the late Pleistocene. The earliest archaeological evidence of inhabitation in Colombia, and one of the oldest in South America, has been found in El Abra, dating to around 12,500 years BP.

This article describes the warfare of the Muisca. The Muisca inhabited the Tenza and Ubaque valleys and the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, the high plateau of the Colombian Eastern Ranges of the Andes in the time before the Spanish conquest. Their society was mainly egalitarian with little difference between the elite class (caciques) and the general people. The Muisca economy was based on agriculture and trading raw materials like cotton, coca, feathers, sea snails and gold with their neighbours. Called "Salt People", they extracted salt from brines in Zipaquirá, Nemocón and Tausa to use for their cuisine and as trading material.

This article describes the art produced by the Muisca. The Muisca established one of the four grand civilisations of the pre-Columbian Americas on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense in present-day central Colombia. Their various forms of art have been described in detail and include pottery, textiles, body art, hieroglyphs and rock art. While their architecture was modest compared to the Inca, Aztec and Maya civilisations, the Muisca are best known for their skilled goldworking. The Museo del Oro in the Colombian capital Bogotá houses the biggest collection of golden objects in the world, from various Colombian cultures including the Muisca.

The Cabildo Mayor del Pueblo Muisca is an organisation of indigenous people, in particular the Muisca. It was established in September 2002 in Bosa, Bogotá, Colombia. The organisation, member of National Indigenous Organization of Colombia (ONIC), focuses on defending the rights of the descendants of the Muisca, and the development of cultural and historical heritage, territory and health and the linguistics of the indigenous language, Muysccubun.

The pre-Columbian cultures of Colombia refers to the ancient cultures and civilizations that inhabited Colombia before the Spanish Conquest in the 16th century.