The Olmecs or Olmec were the earliest known major Mesoamerican civilization, flourishing in the modern-day Mexican states of Veracruz and Tabasco from roughly 1200 to 400 BCE during Mesoamerica's formative period. They were initially centered at the site of their development in San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán, but moved to La Venta in the 10th century BCE following the decline of San Lorenzo. The Olmecs disappeared mysteriously in the 4th century BCE, leaving the region sparsely populated until the 19th century.

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played since at least 1650 BC by the pre-Columbian people of Ancient Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a modernized version of the game, ulama, is still played by the indigenous populations in some places.

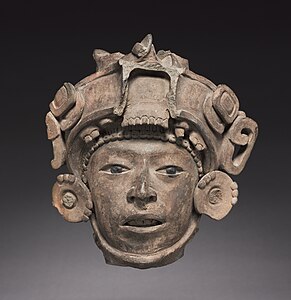

Olmec figurines are archetypical figurines produced by the Formative Period inhabitants of Mesoamerica. While not all of these figurines were produced in the Olmec heartland, they bear the hallmarks and motifs of Olmec culture. While the extent of Olmec control over the areas beyond their heartland is not yet known, Formative Period figurines with Olmec motifs were widespread in the centuries from 1000 to 500 BCE, showing a consistency of style and subject throughout nearly all of Mesoamerica.

El Tajín is a pre-Columbian archeological site in southern Mexico and is one of the largest and most important cities of the Classic era of Mesoamerica. A part of the Classic Veracruz culture, El Tajín flourished from 600 to 1200 AD and during this time numerous temples, palaces, ballcourts, and pyramids were built. From the time the city fell, in 1230, to 1785, no European seems to have known of its existence, until a government inspector chanced upon the Pyramid of the Niches.

Mesoamerican pyramids form a prominent part of ancient Mesoamerican architecture. Although similar in some ways to Egyptian pyramids, these New World structures have flat tops and stairs ascending their faces, more similar to ancient Mesopotamian Ziggurats. The largest pyramid in the world by volume is the Great Pyramid of Cholula, in the east-central Mexican state of Puebla. The builders of certain classic Mesoamerican pyramids have decorated them copiously with stories about the Hero Twins, the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl, Mesoamerican creation myths, ritualistic sacrifice, etc. written in the form of Maya script on the rises of the steps of the pyramids, on the walls, and on the sculptures contained within.

Totonacapan refers to the historical extension where the Totonac people of Mexico dominated, as well as to a region in the modern states of Veracruz and Puebla. The historical territory was much larger than the currently named region, extending from the Cazones River in the north to the Papaloapan River in the south and then west from the Gulf of Mexico into what is now the Sierra Norte de Puebla region and into parts of Hidalgo. When the Spanish arrived, the Totonac ethnicity dominated this large region, although they themselves were dominated by the Aztec Empire. For this reason, they allied with Hernán Cortés against Tenochtitlán. However, over the colonial period, the Totonac population and territory shrank, especially after 1750 when mestizos began infiltrating Totonacapan, taking political and economic power. This continued into the 19th and 20th centuries, prompting the division of most of historical Totonacpan between the states of Puebla and Veracruz. Today, the term refers only to a region in the north of Veracruz where Totonac culture is still important. This region is home to the El Tajín and Cempoala archeological sites as well as Papantla, which is noted for its performance of the Danza de los Voladores.

Bloodletting was the ritualized practice of self-cutting or piercing of an individual's body that served a number of ideological and cultural functions within ancient Mesoamerican societies, in particular the Maya. When performed by ruling elites, the act of bloodletting was crucial to the maintenance of sociocultural and political structure. Bound within the Mesoamerican belief systems, bloodletting was used as a tool to legitimize the ruling lineage's socio-political position and, when enacted, was important to the perceived well-being of a given society or settlement.

A Mesoamerican ballcourt is a large masonry structure of a type used in Mesoamerica for more than 2,700 years to play the Mesoamerican ballgame, particularly the hip-ball version of the ballgame. More than 1,300 ballcourts have been identified, 60% in the last 20 years alone. Although there is a tremendous variation in size, in general all ballcourts are the same shape: a long narrow alley flanked by two walls with horizontal, vertical, and sloping faces. Although the alleys in early ballcourts were open-ended, later ballcourts had enclosed end-zones, giving the structure an -shape when viewed from above.

The Danza de los Voladores, or Palo Volador, is an ancient Mesoamerican ceremony/ritual still performed today, albeit in modified form, in isolated pockets in Mexico. It is believed to have originated with the Nahua, Huastec and Otomi peoples in central Mexico, and then spread throughout most of Mesoamerica. The ritual consists of dance and the climbing of a 30-meter pole from which four of the five participants then launch themselves tied with ropes to descend to the ground. The fifth remains on top of the pole, dancing and playing a flute and drum. According to one myth, the ritual was created to ask the gods to end a severe drought. Although the ritual did not originate with the Totonac people, today it is strongly associated with them, especially those in and around Papantla in the Mexican state of Veracruz. The ceremony was named an Intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO in order to help the ritual survive and thrive in the modern world. The Aztecs believed that Danza de los Voladores was the symbol of their culture.

Remojadas is a name applied to a culture, an archaeological site, as well as an artistic style that flourished on Mexico's Veracruz Gulf Coast from perhaps 100 BCE to 800 CE. The Remojadas culture is considered part of the larger Classic Veracruz culture. Further research into the Remojadas culture is "much needed". The archaeological site has remained largely unexplored since the initial investigations by Alfonso Medellin Zenil in 1949 and 1950.

The Feathered Serpent is a prominent supernatural entity or deity, found in many Mesoamerican religions. It is still called Quetzalcoatl among the Aztecs; Kukulkan among the Yucatec Maya; and Q'uq'umatz and Tohil among the K'iche' Maya.

Cuyuxquihui is an archaeological site located in the Tecolutla valley of Veracruz, Mexico, in the region of the Totonac culture, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) southeast of El Tajín or 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) southeast of Paso de Correo.

Ancient Mesoamericans were the first people to invent rubber balls, sometime before 1600 BCE, and used them in a variety of roles. The Mesoamerican ballgame, for example, employed various sizes of solid rubber balls and balls were burned as offerings in temples, buried in votive deposits, and laid in sacred bogs and cenotes.

The Epi-Olmec culture was a cultural area in the central region of the present-day Mexican state of Veracruz. Concentrated in the Papaloapan River basin, a culture that existed during the Late Formative period, from roughly 300 BCE to roughly 250 CE. Epi-Olmec was a successor culture to the Olmec, hence the prefix "epi-" or "post-". Although Epi-Olmec did not attain the far-reaching achievements of that earlier culture, it did realize, with its sophisticated calendrics and writing system, a level of cultural complexity unknown to the Olmecs.

The Western Mexico shaft tomb tradition refers to a set of interlocked cultural traits found in the western Mexican states of Jalisco, Nayarit, and, to a lesser extent, Colima to its south, roughly dating to the period between 300 BCE and 400 CE, although there is not wide agreement on this end date. Nearly all of the artifacts associated with this shaft tomb tradition have been discovered by looters and are without provenance, making dating problematic.

Huatusco is an archaeological site located in the Carrillo Puerto municipality, near the small, almost deserted town of Santiago Huatusco, on the northern bank of the Rio Atoyac in the Rancho El Fortin. The importance of the site due to the nearly undamaged pyramid from prehispanic times, the largest part of the actual temple is still standing, in the state of Veracruz, Mexico.

Mesa de Cacahuatenco is a Mesoamerican pre-Columbian archeological site, located in the municipality of Ixhuatlán de Madero in northern Veracruz, Mexico, south of the Vinasca River.

La Joya is a Mesoamerican prehispanic archeological site, located in the municipality of Medellín in central Veracruz, Mexico, about 15 kilometers from the port of Veracruz, near the confluence of the Jamapa and Cotaxtla Rivers.

Las Choapas is a recently found archaeological site located within the municipality of Las Choapas, in the southeastern border of the Veracruz State, inside the San Miguel de Allende Ejido, bordering the municipalities of Huimanguillo, Tabasco and Ostuacán, in Chiapas.

Maya ballgame, which is a branch of the Mesoamerican ballgame, is a sporting event that was played throughout the Mesoamerican era by the Maya civilization, which was distributed throughout much of Central America. One of the common links of the Mayan culture of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize is the game played with a rubber ball, about which we have learned from several sources. The Maya ballgame was played with big stone courts. The ball court itself was a focal point of Maya cities and symbolized the city's wealth and power.