Multituberculata is an extinct order of rodent-like mammals with a fossil record spanning over 130 million years. They first appeared in the Middle Jurassic, and reached a peak diversity during the Late Cretaceous and Paleocene. They eventually declined from the mid-Paleocene onwards, disappearing from the known fossil record in the late Eocene. They are the most diverse order of Mesozoic mammals with more than 200 species known, ranging from mouse-sized to beaver-sized. These species occupied a diversity of ecological niches, ranging from burrow-dwelling to squirrel-like arborealism to jerboa-like hoppers. Multituberculates are usually placed as crown mammals outside either of the two main groups of living mammals—Theria, including placentals and marsupials, and Monotremata—but usually as closer to Theria than to monotremes. They are considered to be closely related to Euharamiyida and Gondwanatheria as part of Allotheria.

Purgatorius is a genus of seven extinct eutherian species typically believed to be the earliest example of a primate or protoprimate, a primatomorph precursor to the Plesiadapiformes, dating to as old as 66 million years ago. The first remains were reported in 1965, from what is now eastern Montana's Tullock Formation, specifically at Purgatory Hill in deposits believed to be about 63 million years old, and at Harbicht Hill in the lower Paleocene section of the Hell Creek Formation. Both locations are in McCone County, Montana.

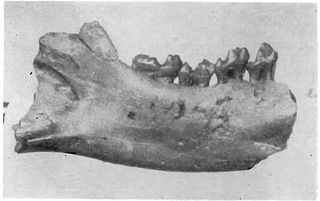

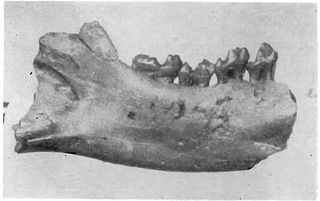

Plesiadapis is one of the oldest known primate-like mammal genera which existed about 58–55 million years ago in North America and Europe. Plesiadapis means "near-Adapis", which is a reference to the adapiform primate of the Eocene period, Adapis. Plesiadapis tricuspidens, the type specimen, is named after the three cusps present on its upper incisors.

Bisonalveus is an extinct genus of shrew-like mammals that were presumably ground-dwelling and fed on plants and insects. Bisonalveus fossils have been discovered in the upper Great Plains region of North America, including sites in modern-day Wyoming, North Dakota, Montana, and Alberta. The fossils have been dated to 60 million years ago, during the Tiffanian North American Stage of the Palaeocene epoch. Bisonalveus is the last known genus of the Pentacodontinae sub-family to have arisen, replacing the genus Coriphagus in the early Tiffanian. Bisonalveus itself appears to have gone extinct by the middle Tiffanian.

Altanius is a genus of extinct primates found in the early Eocene of Mongolia. Though its phylogenetic relationship is questionable, many have placed it as either a primitive omomyid or as a member of the sister group to both adapoids and omomyids. The genus is represented by one species, Altanius orlovi, estimated to weigh about 10–30 g (0.35–1.1 oz) from relatively well-known and complete dental and facial characteristics.

Carpolestes is a genus of extinct primate-like mammals from the late Paleocene of North America. It first existed around 58 million years ago. The three species of Carpolestes appear to form a lineage, with the earliest occurring species, C. dubius, ancestral to the type species, C. nigridens, which, in turn, was ancestral to the most recently occurring species, C. simpsoni.

Ankalagon saurognathus is an extinct carnivorous mammal of the family Mesonychidae, endemic to North America during the Paleocene epoch, existing for approximately 3.1 million years.

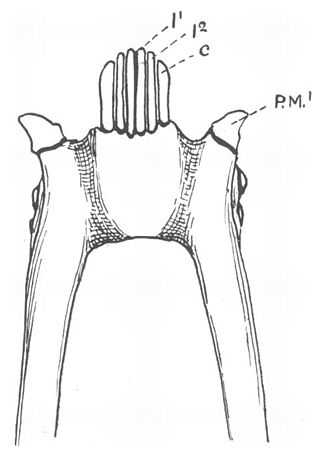

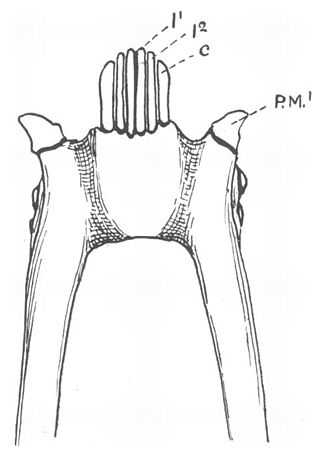

A toothcomb is a dental structure found in some mammals, comprising a group of front teeth arranged in a manner that facilitates grooming, similar to a hair comb. The toothcomb occurs in lemuriform primates, treeshrews, colugos, hyraxes, and some African antelopes. The structures evolved independently in different types of mammals through convergent evolution and vary both in dental composition and structure. In most mammals the comb is formed by a group of teeth with fine spaces between them. The toothcombs in most mammals include incisors only, while in lemuriform primates they include incisors and canine teeth that tilt forward at the front of the lower jaw, followed by a canine-shaped first premolar. The toothcombs of colugos and hyraxes take a different form with the individual incisors being serrated, providing multiple tines per tooth.

The Tiffanian North American Stage on the geologic timescale is the North American faunal stage according to the North American Land Mammal Ages chronology (NALMA), typically set from 60,200,000 to 56,800,000 years BP lasting 3.4 million years.

Cantius is a genus of adapiform primates from the early Eocene of North America and Europe. It is extremely well represented in the fossil record in North America and has been hypothesized to be the direct ancestor of Notharctus in North America. The evolution of Cantius is characterized by a significant increase in body mass that nearly tripled in size. The earliest species were considered small-sized and weighed in around 1 kg (2.2 lb), while the later occurring species were considered medium-sized and likely weighed in around 3 kg (6.6 lb). Though significantly smaller, the fossil remains discovered of the various species of Cantius have striking similarities to that of Notharctus and Smilodectes. It is likely Cantius relied on arboreal quadrupedal locomotion, primarily running and leaping. This locomotor pattern comparable to that of extant lemurs, which has fostered the hypothesis that Cantius and other strepsirrhine adapiforms may have a close phylogenetic affinity to living lemurs.

Microsyops is a plesiadapiform primate found in Middle Eocene in North America. It is in the family Microsyopidae, a plesiadapiform family characterized by distinctive lanceolate lower first incisors. It appears to have had a more developed sense of smell than other early primates. It is believed to have eaten fruit, and its fossils show the oldest known dental cavities in a mammal.

Ignacius is a genus of extinct mammal from the early Cenozoic era. This genus is present in the fossil record from around 62-33 Ma. The earliest known specimens of Ignacius come from the Torrejonian of the Fort Union Formation, Wyoming and the most recent known specimens from Ellesmere Island in northern Canada. Ignacius is one of ten genera within the family Paromomyidae, the longest living family of any plesiadapiforms, persisting for around 30 Ma during the Paleocene and Eocene epochs. The analyses of postcranial fossils by paleontologists suggest that members of the family Paromomyidae, including the genus Ignacius, most likely possessed adaptations for arboreality.

Chiromyoides is a small plesiadapid primatomorph that is known for its unusually robust upper and lower incisors, deep dentary, and comparatively small cheek teeth. Species of Chiromyoides are known from the middle Tiffanian through late Clarkforkian North American Land Mammal Ages (NALMA) of western North America, and from late Paleocene deposits in the Paris Basin, France.

Peradectes is an extinct genus of small metatherian mammals known from the latest Cretaceous to Eocene of North and South America and Europe. The first discovered fossil of P. elegans, was one of 15 Peradectes specimens described in 1921 from the Mason pocket fossil beds in Colorado. The monophyly of the genus has been questioned.

Azygonyx was a small tillodont mammal, likely the size of a cat to raccoon, that lived in North America during the Paleocene and Eocene in the early part of the Cenozoic Era. The only fossils that have been recovered are from the Willwood and Fort Union Formations in the Bighorn Basin of Wyoming, United States, and date to the Clarkforkian to Wasatchian, about 56 to 50 million years ago. Fifty-six collections that have been recovered thus far include the remains of Azygonyx. Azygonyx survived the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum along with other mammals like Phenacodus and Ectocion, both of which were ground-dwelling mammals. Azygonyx probably was a generalist terrestrial mammal that may have roamed around the ground, but was also capable of climbing trees.

Apatemys is a member of the family Apatemyidae, an extinct group of small and insectivorous placental mammals that lived in the Paleogene of North America, India, and Europe. While the number of genera and species is less agreed upon, it has been determined that two apatemyid genera, Apatemys and Sinclairella, existed sequentially during the Eocene in North America. The genus Apatemys, living as far back as 50.3 million years ago (mya), existed through part of the Wasatchian and persisted through the Duchesnean, and Sinclairella followed, existing from the Duchesnean through the Arikareean. Examinations of specimens belonging to the genus Apatemys suggest adaptations characteristic of arboreal mammals.

Carpodaptes was a genus that encompassed small, insectivorous animals that roamed the Earth during the Late Paleocene. Specifically, Carpodaptes can be found between the Tiffanian and Clarkforkian periods of North America. Although little evidence, this genus may have made it through to the early Eocene. They are known primarily from collections of jaw and teeth fragments in North America, mainly in southwestern Canada and northwestern America. Carpodaptes are estimated to have weighed approximately 53-96 grams which made them a little bigger than a mouse. However small, Carpodaptes was a placental mammal within the order Plesiadapiformes that appeared to have a high fiber diet. This insect-eating mammal may have been one of the first to evolve fingernails in place of claws. This may have helped them pick insects, nuts, and seeds more easily off the ground than with paws or claws. Carpodaptes was thought to only exist in North America but recent discoveries of dentition fragments have been found in China.

Uintasorex is a genus of primate which lived in North America during the Eocene epoch. Fossils belonging to Uintasorex have been dated to the Bridgerian and Uintan stages, roughly 50.3 to 42 million years ago.

Saxonella is a genus of extinct primate from the Paleocene Epoch, 66–56 Ma. The genus is present in the fossil record from around ~62–57 Ma. Saxonella has been found in fissure fillings in Walbeck, Germany as well as in the Paskapoo Formation in Alberta, Canada. Saxonella is one of five families within the superfamily Plesiadapoidae, which appears in the fossil record from the mid Paleocene to the early Eocene. Analyses of molars by paleontologists suggest that Saxonella most likely had a folivorous diet.

Torrejonia is a genus of extinct plesiadapiform that belongs to the family Palaechthonidae. There are currently two species known, T. wilsoni and T. sirokyi. This genus is present in the fossil record from around 62–58 Ma. Species belonging to this genus are suggested to be plesiadapiforms based on adaptations observed in the skeletal morphology consistent with arboreal locomotor behavior. Following the mass extinction event at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (K-Pg), a large diversity of plesiadapiform families were documented beginning at the Torrejonian NALMA. Research has shown that T. wilsoni is one of the largest palaechthonids and is reconstructed as being more frugivorous than other palaechthonids.