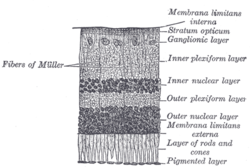

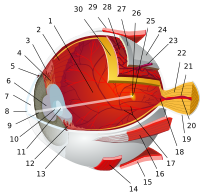

The retina is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which translates that image into electrical neural impulses to the brain to create visual perception. The retina serves a function analogous to that of the film or image sensor in a camera.

Neuropil is any area in the nervous system composed of mostly unmyelinated axons, dendrites and glial cell processes that forms a synaptically dense region containing a relatively low number of cell bodies. The most prevalent anatomical region of neuropil is the brain which, although not completely composed of neuropil, does have the largest and highest synaptically concentrated areas of neuropil in the body. For example, the neocortex and olfactory bulb both contain neuropil.

A photoreceptor cell is a specialized type of neuroepithelial cell found in the retina that is capable of visual phototransduction. The great biological importance of photoreceptors is that they convert light into signals that can stimulate biological processes. To be more specific, photoreceptor proteins in the cell absorb photons, triggering a change in the cell's membrane potential.

Rod cells are photoreceptor cells in the retina of the eye that can function in lower light better than the other type of visual photoreceptor, cone cells. Rods are usually found concentrated at the outer edges of the retina and are used in peripheral vision. On average, there are approximately 92 million rod cells in the human retina. Rod cells are more sensitive than cone cells and are almost entirely responsible for night vision. However, rods have little role in color vision, which is the main reason why colors are much less apparent in dim light.

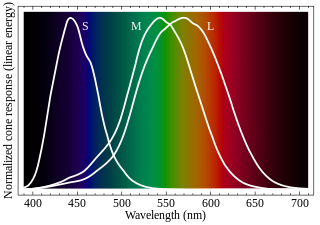

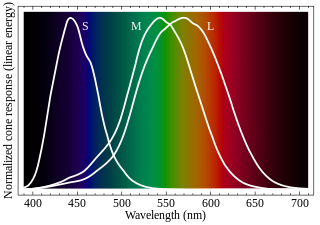

Cone cells, or cones, are photoreceptor cells in the retinas of vertebrate eyes including the human eye. They respond differently to light of different wavelengths, and are thus responsible for color vision, and function best in relatively bright light, as opposed to rod cells, which work better in dim light. Cone cells are densely packed in the fovea centralis, a 0.3 mm diameter rod-free area with very thin, densely packed cones which quickly reduce in number towards the periphery of the retina. Conversely, they are absent from the optic disc, contributing to the blind spot. There are about six to seven million cones in a human eye and are most concentrated towards the macula.

The fovea centralis is a small, central pit composed of closely packed cones in the eye. It is located in the center of the macula lutea of the retina.

As a part of the retina, bipolar cells exist between photoreceptors and ganglion cells. They act, directly or indirectly, to transmit signals from the photoreceptors to the ganglion cells.

Amacrine cells are interneurons in the retina. They are named from the Greek roots a– ("non"), makr– ("long") and in– ("fiber"), because of their short neuritic processes. Amacrine cells are inhibitory neurons, and they project their dendritic arbors onto the inner plexiform layer (IPL), they interact with retinal ganglion cells and/or bipolar cells.

Horizontal cells are the laterally interconnecting neurons having cell bodies in the inner nuclear layer of the retina of vertebrate eyes. They help integrate and regulate the input from multiple photoreceptor cells. Among their functions, horizontal cells are believed to be responsible for increasing contrast via lateral inhibition and adapting both to bright and dim light conditions. Horizontal cells provide inhibitory feedback to rod and cone photoreceptors. They are thought to be important for the antagonistic center-surround property of the receptive fields of many types of retinal ganglion cells.

The tunica media, or media for short, is the middle tunica (layer) of an artery or vein. It lies between the tunica intima on the inside and the tunica externa on the outside.

The inner plexiform layer is an area of the retina that is made up of a dense reticulum of fibrils formed by interlaced dendrites of retinal ganglion cells and cells of the inner nuclear layer. Within this reticulum a few branched spongioblasts are sometimes embedded.

The elements composing the Layer of Rods and Cones in the retina of the eye are of two kinds, rod cells and cone cells, the former being much more numerous than the latter except in the macula lutea.

The pigmented layer of retina or retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is the pigmented cell layer just outside the neurosensory retina that nourishes retinal visual cells, and is firmly attached to the underlying choroid and overlying retinal visual cells.

The inner nuclear layer or layer of inner granules, of the retina, is made up of a number of closely packed cells, of which there are three varieties, viz.: bipolar cells, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells.

The outer nuclear layer, is one of the layers of the vertebrate retina, the light-detecting portion of the eye. Like the inner nuclear layer, the outer nuclear layer contains several strata of oval nuclear bodies; they are of two kinds, viz.: rod and cone granules, so named on account of their being respectively connected with the rods and cones of the next layer.

The retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) or nerve fiber layer, stratum opticum, is formed by the expansion of the fibers of the optic nerve; it is thickest near the optic disc, gradually diminishing toward the ora serrata.

The ganglion cell layer is a layer of the retina that consists of retinal ganglion cells and displaced amacrine cells.

Mammals normally have a pair of eyes. Although mammalian vision is not so excellent as bird vision, it is at least dichromatic for most of mammalian species, with certain families possessing a trichromatic color perception.

Anatomical terminology is used to describe microanatomical structures. This helps describe precisely the structure, layout and position of an object, and minimises ambiguity. An internationally accepted lexicon is Terminologia Histologica.

AII amacrine cells are a subtype of amacrine cells present in the retina of mammals. AII amacrine cell serve the critical role of transferring light signals from rod photoreceptors to the retinal ganglion cells