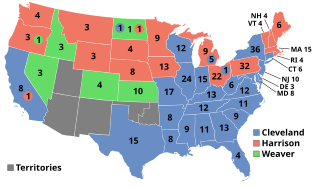

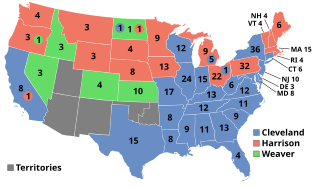

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 8, 1892. In the fourth rematch in American history, the Democratic nominee, former president Grover Cleveland, defeated the incumbent Republican President Benjamin Harrison. Cleveland's victory made him the first president in American history to be elected to a non-consecutive second term, a feat not repeated until Donald Trump was elected in 2024. This was the first of two occasions when incumbents were defeated in consecutive elections—the second being Gerald Ford's loss in 1976 to Jimmy Carter followed by Carter's loss in 1980 to Ronald Reagan. The 1892 election saw the incumbent White House party defeated in three consecutive elections, which did not occur again until 2024.

The People's Party, usually known as the populist party or simply the Populists, was an agrarian populist political party in the United States in the late 19th century. The Populist Party emerged in the early 1890s as an important force in the Southern and Western United States, but declined rapidly after the 1896 United States presidential election in which most of its natural constituency was absorbed by the Bryan wing of the Democratic Party. A rump faction of the party continued to operate into the first decade of the 20th century, but never matched the popularity of the party in the early 1890s.

Populism is a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of the common people and often position this group in opposition to a perceived elite group. It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed in the late 19th century and has been applied to various politicians, parties and movements since that time, often as a pejorative. Within political science and other social sciences, several different definitions of populism have been employed, with some scholars proposing that the term be rejected altogether.

American electoral politics have been dominated by successive pairs of major political parties since shortly after the founding of the republic of the United States. Since the 1850s, the two largest political parties have been the Democratic Party and the Republican Party—which together have won every United States presidential election since 1852 and controlled the United States Congress since at least 1856. Despite keeping the same names, the two parties have evolved in terms of ideologies, positions, and support bases over their long lifespans, in response to social, cultural, and economic developments—the Democratic Party being the left-of-center party since the time of the New Deal, and the Republican Party now being the right-of-center party.

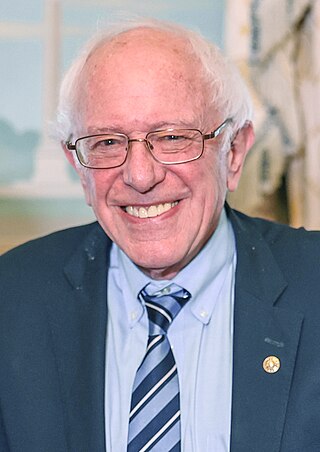

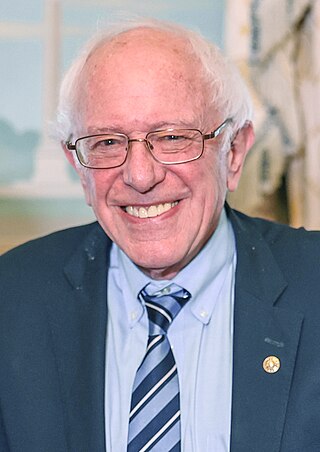

Bernard Sanders is an American politician and activist who is the senior United States senator from Vermont. Sanders is the longest-serving independent in U.S. congressional history, but maintains a close relationship with the Democratic Party, having caucused with House and Senate Democrats for most of his congressional career and sought the party's presidential nomination in 2016 and 2020.

Thomas Carr Frank is an American political analyst, historian, and journalist. He co-founded and edited The Baffler magazine. Frank is the author of the books What's the Matter with Kansas? (2004) and Listen, Liberal (2016), among others. From 2008 to 2010 he wrote "The Tilting Yard", a column in The Wall Street Journal.

Progressivism in the United States is a left-leaning political philosophy and reform movement. Into the 21st century, it advocates policies that are generally considered social democratic and part of the American Left. It has also expressed itself within center-right politics, such as progressive conservatism. It reached its height early in the 20th century. Middle/working class and reformist in nature, it arose as a response to the vast changes brought by modernization, such as the growth of large corporations, pollution, and corruption in American politics. Historian Alonzo Hamby describes American progressivism as a "political movement that addresses ideas, impulses, and issues stemming from modernization of American society. Emerging at the end of the nineteenth century, it established much of the tone of American politics throughout the first half of the century."

The Democratic Party is one of the two major political parties of the United States political system and the oldest active political party in the country, as well as in the world. The Democratic Party was founded in 1828. It is also the oldest active voter-based political party in the world. The party has changed significantly during its nearly two centuries of existence. Once known as the party of the "common man", the early Democratic Party stood for individual rights and state sovereignty, and opposed banks and high tariffs. In the first decades of its existence, from 1832 to the mid-1850s, under Presidents Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, and James K. Polk, the Democrats usually bested the opposition Whig Party by narrow margins.

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right populism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establishment, and speaking to or for the common people. Recurring themes of right-wing populists include neo-nationalism, social conservatism, economic nationalism and fiscal conservatism. Frequently, they aim to defend a national culture, identity, and economy against perceived attacks by outsiders. Right-wing populism has associations with authoritarianism, while some far-right populists draw comparisons to fascism.

The Democratic Party of the United States is a party composed of various factions. The liberal faction supports modern liberalism that began with the New Deal in the 1930s and continued with both the New Frontier and Great Society in the 1960s. The moderate faction supports Third Way politics that includes center-left social policies and centrist fiscal policies. The progressive faction supports progressivism.

American political ideologies conventionally align with the left–right political spectrum, with most Americans identifying as conservative, liberal, or moderate. Contemporary American conservatism includes social conservatism and fiscal conservatism. The former ideology developed as a response to communism and the civil rights movement, while the latter developed as a response to the New Deal. Contemporary American liberalism includes social liberalism and progressivism, developing during the Progressive Era and the Great Depression. Besides conservatism and liberalism, the United States has a notable libertarian movement, developing during the mid-20th century as a revival of classical liberalism. Historical political movements in the United States have been shaped by ideologies as varied as republicanism, populism, separatism, fascism, socialism, monarchism, and nationalism.

Left-wing populism, also called social populism, is a political ideology that combines left-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric often includes elements of anti-elitism, opposition to the Establishment, and speaking for the "common people". Recurring themes for left-wing populists include economic democracy, social justice, and skepticism of globalization. Socialist theory plays a lesser role than in traditional left-wing ideologies.

Progressivism is a left-leaning political philosophy and reform movement that seeks to advance the human condition through social reform – primarily based on purported advancements in social organization, science, and technology. Adherents hold that progressivism has universal application and endeavor to spread this idea to human societies everywhere. Progressivism arose during the Age of Enlightenment out of the belief that civility in Europe was improving due to the application of new empirical knowledge.

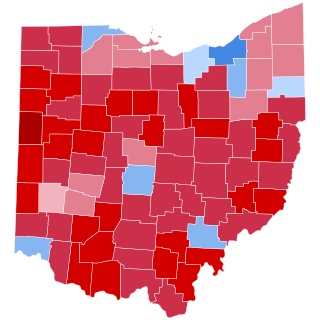

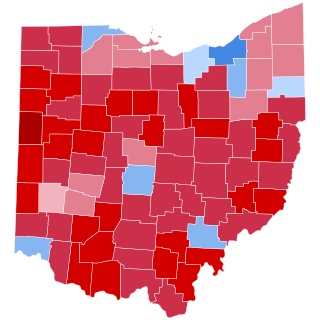

The 2016 United States presidential election in Ohio was held on Tuesday, November 8, 2016, as part of the 2016 United States presidential election in which all 50 states plus the District of Columbia participated. Ohio voters chose electors to represent them in the Electoral College via a popular vote, pitting the Republican Party's nominee, businessman Donald Trump, and running mate Indiana Governor Mike Pence against Democratic Party nominee, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and her running mate Virginia Senator Tim Kaine. Ohio had 18 electoral votes in the Electoral College.

The 1896 United States presidential election in Idaho took place on November 3, 1896. All contemporary 45 states were part of the 1896 United States presidential election. State voters chose three electors to the Electoral College, which selected the president and vice president.

The People's Party is a syncretic political organization in the United States aimed at "forming a major new political party free of corporate money and influence."

In the United States, Sanders–Trump voters, also known as Bernie–Trump voters, are Americans who voted for Bernie Sanders in the 2016 or 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries, but who subsequently voted for Republican Party nominee Donald Trump in the general election. In the 2016 U.S. presidential election, these voters composed an estimated 6%-12% of Sanders supporters.

"Radicalism" or "radical liberalism" was a political ideology in the 19th century United States aimed at increasing political and economic equality. The ideology was rooted in a belief in the power of the ordinary man, political equality, and the need to protect civil liberties.