Motor neuron diseases or motor neurone diseases (MNDs) are a group of rare neurodegenerative disorders that selectively affect motor neurons, the cells which control voluntary muscles of the body. They include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), progressive bulbar palsy (PBP), pseudobulbar palsy, progressive muscular atrophy (PMA), primary lateral sclerosis (PLS), spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and monomelic amyotrophy (MMA), as well as some rarer variants resembling ALS.

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT) is a hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy of the peripheral nervous system characterized by progressive loss of muscle tissue and touch sensation across various parts of the body. This disease is the most commonly inherited neurological disorder, affecting about one in 2,500 people. It is named after those who classically described it: the Frenchman Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893), his pupil Pierre Marie (1853–1940), and the Briton Howard Henry Tooth (1856–1925).

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 75% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe symptoms develop such as headache, neck stiffness, and paresthesia. These symptoms usually pass within one or two weeks. A less common symptom is permanent paralysis, and possible death in extreme cases. Years after recovery, post-polio syndrome may occur, with a slow development of muscle weakness similar to what the person had during the initial infection.

Myalgia or muscle pain is a painful sensation evolving from muscle tissue. It is a symptom of many diseases. The most common cause of acute myalgia is the overuse of a muscle or group of muscles; another likely cause is viral infection, especially when there has been no injury.

Benign fasciculation syndrome (BFS) is characterized by fasciculation (twitching) of voluntary muscles in the body. The twitching can occur in any voluntary muscle group but is most common in the eyelids, arms, hands, fingers, legs, and feet. The tongue can also be affected. The twitching may be occasional to continuous. BFS must be distinguished from other conditions that include muscle twitches.

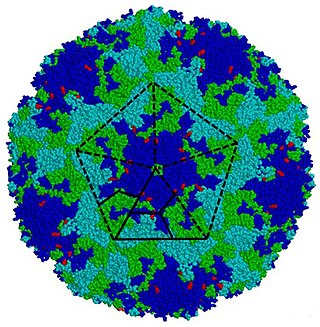

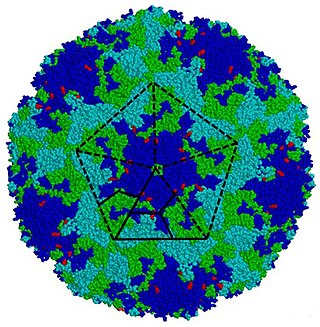

Poliovirus, the causative agent of polio, is a serotype of the species Enterovirus C, in the family of Picornaviridae. There are three poliovirus serotypes, numbered 1, 2, and 3.

Enterovirus is a genus of positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses associated with several human and mammalian diseases. Enteroviruses are named by their transmission-route through the intestine.

Exercise intolerance is a condition of inability or decreased ability to perform physical exercise at the normally expected level or duration for people of that age, size, sex, and muscle mass. It also includes experiences of unusually severe post-exercise pain, fatigue, nausea, vomiting or other negative effects. Exercise intolerance is not a disease or syndrome in and of itself, but can result from various disorders.

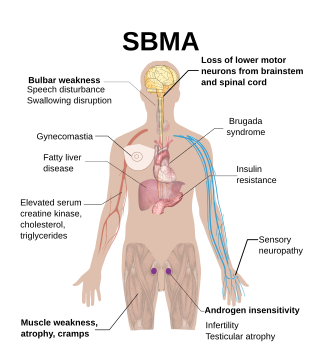

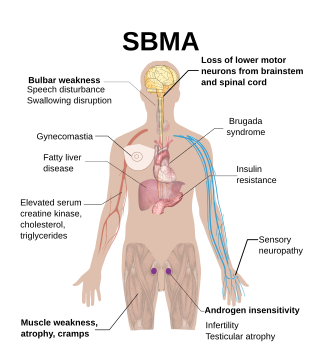

Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), popularly known as Kennedy's disease, is a rare, adult-onset, X-linked recessive lower motor neuron disease caused by trinucleotide CAG repeat expansions in exon 1 of the androgen receptor (AR) gene, which results in both loss of AR function and toxic gain of function.

In neuroscience, nerve conduction velocity (CV) is the speed at which an electrochemical impulse propagates down a neural pathway. Conduction velocities are affected by a wide array of factors, which include age, sex, and various medical conditions. Studies allow for better diagnoses of various neuropathies, especially demyelinating diseases as these conditions result in reduced or non-existent conduction velocities. CV is an important aspect of nerve conduction studies.

Fazio–Londe disease (FLD), also called progressive bulbar palsy of childhood, is a very rare inherited motor neuron disease of children and young adults and is characterized by progressive paralysis of muscles innervated by cranial nerves. FLD, along with Brown–Vialetto–Van Laere syndrome (BVVL), are the two forms of infantile progressive bulbar palsy, a type of progressive bulbar palsy in children.

Flaccid paralysis is a neurological condition characterized by weakness or paralysis and reduced muscle tone without other obvious cause. This abnormal condition may be caused by disease or by trauma affecting the nerves associated with the involved muscles. For example, if the somatic nerves to a skeletal muscle are severed, then the muscle will exhibit flaccid paralysis. When muscles enter this state, they become limp and cannot contract. This condition can become fatal if it affects the respiratory muscles, posing the threat of suffocation. It also occurs in the spinal shock stage in complete transection of the spinal cord occurring in injuries such as gunshot wounds.

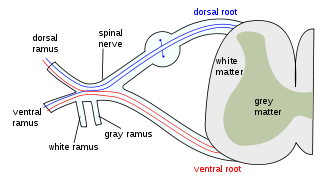

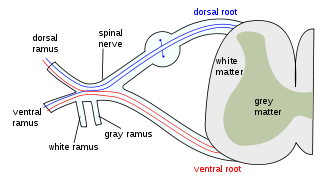

A lower motor neuron lesion is a lesion which affects nerve fibers traveling from the lower motor neuron(s) in the anterior horn/anterior grey column of the spinal cord, or in the motor nuclei of the cranial nerves, to the relevant muscle(s).

The history of polio (poliomyelitis) infections began during prehistory. Although major polio epidemics were unknown before the 20th century, the disease has caused paralysis and death for much of human history. Over millennia, polio survived quietly as an endemic pathogen until the 1900s when major epidemics began to occur in Europe. Soon after, widespread epidemics appeared in the rest of the world. By 1910, frequent epidemics became regular events throughout the developed world primarily in cities during the summer months. At its peak in the 1940s and 1950s, polio would paralyze or kill over half a million people worldwide every year.

Thyrotoxic myopathy (TM) is a neuromuscular disorder that develops due to the overproduction of the thyroid hormone thyroxine. Also known as hyperthyroid myopathy, TM is one of many myopathies that lead to muscle weakness and muscle tissue breakdown. Evidence indicates the onset may be caused by hyperthyroidism. Physical symptoms of TM may include muscle weakness, the breakdown of muscle tissue, fatigue, and heat intolerance. Physical acts such as lifting objects and climbing stairs may become increasingly difficult. If untreated, TM can be an extremely debilitating disorder that can, in extreme rare cases, lead to death. If diagnosed and treated properly the effects can be controlled and in most cases reversed leaving no lasting effects.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neurone disease (MND) or Lou Gehrig's disease (LGD), is a rare, terminal neurodegenerative disorder that results in the progressive loss of both upper and lower motor neurons that normally control voluntary muscle contraction. ALS is the most common form of the motor neuron diseases. ALS often presents in its early stages with gradual muscle stiffness, twitches, weakness, and wasting. Motor neuron loss typically continues until the abilities to eat, speak, move, and, lastly, breathe are all lost. While only 15% of people with ALS also fully develop frontotemporal dementia, an estimated 50% face at least some minor difficulties with thinking and behavior. Depending on which of the aforementioned symptoms develops first, ALS is classified as limb-onset or bulbar-onset.

Denervation is any loss of nerve supply regardless of the cause. If the nerves lost to denervation are part of the neuronal communication to a specific function in the body then altered or a loss of physiological functioning can occur. Denervation can be caused by injury or be a symptom of a disorder like ALS, post-polio syndrome, or POTS. Additionally, it can be a useful surgical technique to alleviate major negative symptoms, such as in renal denervation. Denervation can have many harmful side effects such as increased risk of infection and tissue dysfunction.

Alternating hemiplegia is a form of hemiplegia that has an ipsilateral cranial nerve palsies and contralateral hemiplegia or hemiparesis of extremities of the body. The disorder is characterized by recurrent episodes of paralysis on one side of the body. There are multiple forms of alternating hemiplegia, Weber's syndrome, middle alternating hemiplegia, and inferior alternating hemiplegia. This type of syndrome can result from a unilateral lesion in the brainstem affecting both upper motor neurons and lower motor neurons. The muscles that would receive signals from these damaged upper motor neurons result in spastic paralysis. With a lesion in the brainstem, this affects the majority of limb and trunk muscles on the contralateral side due to the upper motor neurons decussation after the brainstem. The cranial nerves and cranial nerve nuclei are also located in the brainstem making them susceptible to damage from a brainstem lesion. Cranial nerves III (Oculomotor), VI (Abducens), and XII (Hypoglossal) are most often associated with this syndrome given their close proximity with the pyramidal tract, the location which upper motor neurons are in on their way to the spinal cord. Damages to these structures produce the ipsilateral presentation of paralysis or palsy due to the lack of cranial nerve decussation before innervating their target muscles. The paralysis may be brief or it may last for several days, many times the episodes will resolve after sleep. Some common symptoms of alternating hemiplegia are mental impairment, gait and balance difficulties, excessive sweating and changes in body temperature.

Polioencephalitis is a viral infection of the brain, causing inflammation within the grey matter of the brain stem. The virus has an affinity for neuronal cell bodies and has been found to affect mostly the midbrain, pons, medulla and cerebellum of most infected patients. The infection can reach up through the thalamus and hypothalamus and possibly reach the cerebral hemispheres. The infection is caused by the poliomyelitis virus which is a single-stranded, positive sense RNA virus surrounded by a non-enveloped capsid. Humans are the only known natural hosts of this virus. The disease has been eliminated from the U.S. since the mid-twentieth century, but is still found in certain areas of the world such as Africa.

Post-acute infection syndromes (PAISs) or post-infectious syndromes are medical conditions characterized by symptoms attributed to a prior infection. While it is commonly assumed that people either recover or die from infections, long-term symptoms—or sequelae—are a possible outcome as well. Examples include long COVID, Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), and post-Ebola virus syndrome. Common symptoms include post-exertional malaise (PEM), severe fatigue, neurocognitive symptoms, flu-like symptoms, and pain. The pathology of most of these conditions is not understood and management is generally symptomatic.