The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was a historical period of Germany from 9 November 1918 to 23 March 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclaimed itself, as the German Republic. The period's informal name is derived from the city of Weimar, which hosted the constituent assembly that established its government. In English, the republic was usually simply called "Germany", with "Weimar Republic" not commonly used until the 1930s.

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the status quo ante—the previous political state of society—which the person believes possessed positive characteristics that are absent from contemporary society. As a descriptor term, reactionary derives from the ideological context of the left–right political spectrum. As an adjective, the word reactionary describes points of view and policies meant to restore a status quo ante.

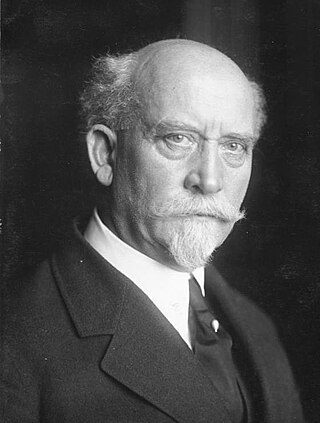

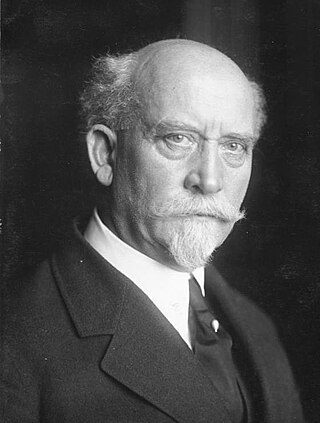

Heinrich Aloysius Maria Elisabeth Brüning was a German Centre Party politician and academic, who served as the chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic from 1930 to 1932.

The German People's Party was a conservative-liberal political party during the Weimar Republic that was the successor to the National Liberal Party of the German Empire. Along with the left-liberal German Democratic Party (DDP), it represented political liberalism in Germany between 1918 and 1933.

Reichswehr was the official name of the German armed forces during the Weimar Republic and the first years of the Third Reich. After Germany was defeated in World War I, the Imperial German Army was dissolved in order to be reshaped into a peacetime army. From it a provisional Reichswehr was formed in March 1919. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the rebuilt German Army was subject to severe limitations in size, structure and armament. The official formation of the Reichswehr took place on 1 January 1921 after the limitations had been met. The German armed forces kept the name Reichswehr until Adolf Hitler's 1935 proclamation of the "restoration of military sovereignty", at which point it became part of the new Wehrmacht.

Der Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten, commonly known as Der Stahlhelm, was a German First World War veteran's organisation existing from 1918 to 1935. In the late days of the Weimar Republic, it was closely affiliated to the monarchist German National People's Party (DNVP), placed at party gatherings in the position of armed security guards.

Philipp Heinrich Scheidemann was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). In the first quarter of the 20th century he played a leading role in both his party and in the young Weimar Republic. During the German Revolution of 1918–1919 that broke out after Germany's defeat in World War I, Scheidemann proclaimed a German Republic from a balcony of the Reichstag building. In 1919 he was elected Reich Minister President by the National Assembly meeting in Weimar to write a constitution for the republic. He resigned the office the same year due to a lack of unanimity in the cabinet on whether or not to accept the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

Othmar Spann was a conservative Austrian philosopher, sociologist and economist. His radical anti-liberal and anti-socialist views, based on early 19th century Romantic ideas expressed by Adam Müller et al. and popularized in his books and lecture courses, helped antagonise political factions in Austria during the interwar years.

The Bavarian People's Party was a Catholic political party in Bavaria during the Weimar Republic. After the collapse of the German Empire in 1918, it split away from the national-level Catholic Centre Party and formed the BVP in order to pursue a more conservative and particularist Bavarian course. It consistently had more seats in the Bavarian state parliament than any other party and provided all Bavarian minister presidents from 1920 on. In the national Reichstag it remained a minor player with only about three percent of total votes in all elections. The BVP disbanded shortly after the Nazi seizure of power in early 1933.

The German revolution of 1918–1919, also known as the November Revolution, was an uprising started by workers and soldiers in the final days of World War I. It quickly and almost bloodlessly brought down the German Empire, then in its more violent second stage, the supporters of a parliamentary republic were victorious over those who wanted a soviet-style council republic. The defeat of the forces of the far Left cleared the way for the establishment of the Weimar Republic.

In the fourteen years the Weimar Republic was in existence, some forty parties were represented in the Reichstag. This fragmentation of political power was in part due to the use of a peculiar proportional representation electoral system that encouraged regional or small special interest parties and in part due to the many challenges facing the nascent German democracy in this period.

The Conservative Revolution, also known as the German neoconservative movement, or new nationalism, was a German national-conservative movement prominent during the Weimar Republic and Austria, in the years 1918–1933.

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, also known as the Munich Soviet Republic, was a short-lived unrecognised socialist state in Bavaria during the German Revolution of 1918–1919. It took the form of a workers' council republic. Its name is also sometimes rendered in English as the Bavarian Council Republic; the German term Räterepublik means a republic of councils or committees, and council or committee is also the meaning of the Russian word soviet. It was established in April 1919 after the demise of Kurt Eisner's government and sought to establish a soviet republic in Bavaria. It was overthrown less than a month later by elements of the German Army and the paramilitary Freikorps. Several individuals involved in its overthrow later joined the Nazi Party.

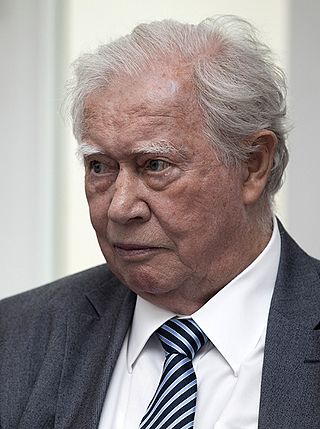

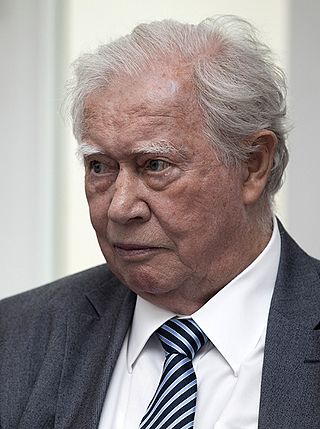

Hans Mommsen was a German historian, known for his studies in German social history, for his functionalist interpretation of the Third Reich, and especially for arguing that Adolf Hitler was a weak dictator. Descended from Nobel Prize-winning historian Theodor Mommsen, he was a member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.

Karl Dietrich Bracher was a German political scientist and historian of the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany. Born in Stuttgart, Bracher was awarded a Ph.D. in the classics by the University of Tübingen in 1948 and subsequently studied at Harvard University from 1949 to 1950. During World War II, he served in the Wehrmacht and was captured by the Americans while serving in Tunisia in 1943. Bracher taught at the Free University of Berlin from 1950 to 1958 and at the University of Bonn since 1959. In 1951, Bracher married Dorothee Schleicher, the niece of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. They had two children.

The Free State of Prussia was one of the constituent states of Germany from 1918 to 1947. The successor to the Kingdom of Prussia after the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, it continued to be the dominant state in Germany during the Weimar Republic, as it had been during the empire, even though most of Germany's post-war territorial losses in Europe had come from its lands. It was home to the federal capital Berlin and had 62% of Germany's territory and 61% of its population. Prussia changed from the authoritarian state it had been in the past and became a parliamentary democracy under its 1920 constitution. During the Weimar period it was governed almost entirely by pro-democratic parties and proved more politically stable than the Republic itself. With only brief interruptions, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) provided the Minister President. Its Ministers of the Interior, also from the SPD, pushed republican reform of the administration and police, with the result that Prussia was considered a bulwark of democracy within the Weimar Republic.

Jeffrey C. Herf is an American historian of modern Europe, particularly modern Germany. He is Distinguished University Professor, of modern European history, Emeritus at the University of Maryland, College Park.

The Reichsbanner Schwarz-Rot-Gold was an organization in Germany during the Weimar Republic with the goal to defend German parliamentary democracy against internal subversion and extremism from the left and right and to compel the population to respect and honor the new Republic's flag and constitution. It was formed by members of the left-wing Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the centre-right to right-wing German Centre Party, and the centrist German Democratic Party in February 1924.

Reactionary modernism is a term first coined by Jeffrey Herf in the 1980s to describe the mixture of "great enthusiasm for modern technology with a rejection of the Enlightenment and the values and institutions of liberal democracy" that was characteristic of the German Conservative Revolutionary movement and Nazism. In turn, this ideology of reactionary modernism was closely linked to the original, positive view of the Sonderweg, which saw Germany as the great Central European power, neither of the West nor of the East.

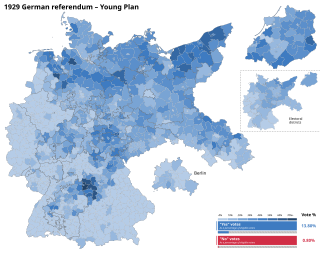

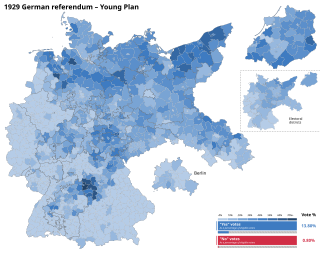

The 1929 German Referendum was an attempt during the Weimar Republic to use popular legislation to annul the agreement in the Young Plan between the German government and the World War I opponents of the German Reich regarding the amount and conditions of reparations payments. The referendum was the result of the initiative "Against the Enslavement of the German People " launched in 1929 by right-wing parties and organizations. It called for an overall revision of the Treaty of Versailles and stipulated that government officials who accepted new reparation obligations would be committing treason.