A torch is a stick with combustible material at one end which can be used as a light source or to set something on fire. Torches have been used throughout history, and are still used in processions, symbolic and religious events, and in juggling entertainment. In some countries, notably the United Kingdom and Australia, "torch" in modern usage is also the term for a battery-operated portable light.

A candle is an ignitable wick embedded in wax, or another flammable solid substance such as tallow, that provides light, and in some cases, a fragrance. A candle can also provide heat or a method of keeping time. Candles have been used for over two millennia around the world, and were a significant form of indoor lighting until the invention of other types of light sources. Although electric light has largely made candle use nonessential for illumination, candles are still commonly used for functional, symbolic and aesthetic purposes and in specific cultural and religious settings.

Tallow is a rendered form of beef or mutton suet, primarily made up of triglycerides.

A lantern is an often portable source of lighting, typically featuring a protective enclosure for the light source – historically usually a candle, a wick in oil, or a thermoluminescent mesh, and often a battery-powered light in modern times – to make it easier to carry and hang up, and make it more reliable outdoors or in drafty interiors. Lanterns may also be used for signaling, as torches, or as general light-sources outdoors.

Pith, or medulla, is a tissue in the stems of vascular plants. Pith is composed of soft, spongy parenchyma cells, which in some cases can store starch. In eudicotyledons, pith is located in the center of the stem. In monocotyledons, it extends only into roots. The pith is encircled by a ring of xylem; the xylem, in turn, is encircled by a ring of phloem.

Juncaceae is a family of flowering plants, commonly known as the rush family. It consists of 8 genera and about 464 known species of slow-growing, rhizomatous, herbaceous monocotyledonous plants that may superficially resemble grasses and sedges. They often grow on infertile soils in a wide range of moisture conditions. The best-known and largest genus is Juncus. Most of the Juncus species grow exclusively in wetland habitats. A few rushes, such as Juncus bufonius are annuals, but most are perennials. Despite the apparent similarity, Juncaceae are not counted among the plants with the vernacular name bulrush.

Rendering is a process that converts waste animal tissue into stable, usable materials. Rendering can refer to any processing of animal products into more useful materials, or, more narrowly, to the rendering of whole animal fatty tissue into purified fats like lard or tallow. Rendering can be carried out on an industrial, farm, or kitchen scale. It can also be applied to non-animal products that are rendered down to pulp. The rendering process simultaneously dries the material and separates the fat from the bone and protein, yielding a fat commodity and a protein meal.

A votive candle or prayer candle is a small candle, typically white or beeswax yellow, intended to be burnt as a votive offering in an act of Christian prayer, especially within the Anglican, Lutheran, and Roman Catholic Christian denominations, among others. In Christianity, votive candles are commonplace in many churches, as well as home altars, and symbolize the "prayers the worshipper is offering for him or herself, or for other people." The size of a votive candle is often two inches tall by one and a half inches diameter, although other votive candles can be significantly taller and wider. In other religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, similar offerings exist, which include diyas and butter lamps.

Juncus effusus is a perennial herbaceous flowering plant species in the rush family Juncaceae, with the common names common rush or soft rush. In North America, the common name soft rush also refers to Juncus interior.

Candle making was developed independently in a number of countries around the world.

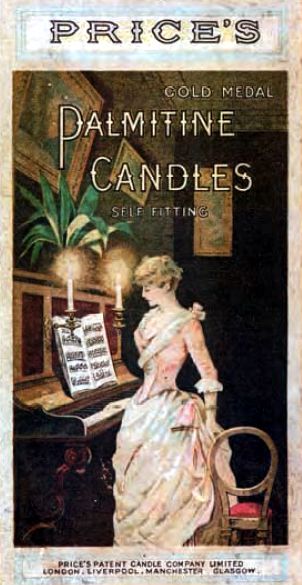

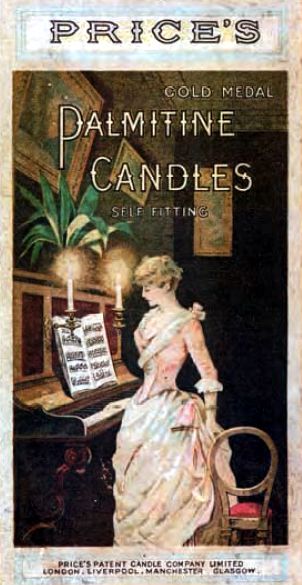

Price's Candles, founded in 1830, is an importer and retailer of candles headquartered in Bedford, England. The company holds the royal warrant of appointment for the supply of candles and is one of the largest candle suppliers in the United Kingdom.

A candle wick or lamp wick is usually made of braided cotton that holds the flame of a candle or oil lamp. A candle wick works by capillary action, conveying ("wicking") the fuel to the flame. When the liquid fuel, typically melted candle wax, reaches the flame it then vaporizes and combusts. In other words, the wick brings the liquified wax up into the flame to burn. The candle wick influences how the candle burns. Important characteristics of the wick include diameter, stiffness, fire-resistance, and tethering.

A candelabra or candelabrum is a candle holder with multiple arms. Candelabras can be used to describe a variety of candle holders including chandeliers, however, candelabras can also be distinguished as branched candle holders that are placed on a surface such as the floor, stand, or tabletop, unlike chandeliers which are hung from the ceiling.

The Betty lamp is a lamp thought to be of German, Austrian, or Hungarian origin. It came into use in the 18th century. They were commonly made of iron or brass and were most often used in the home or workshop. These lamps burned fish oil or fat trimmings and had wicks of twisted cloth.

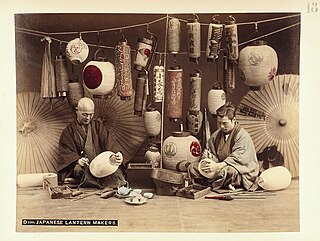

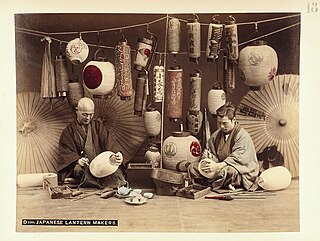

The traditional lighting equipment of Japan includes the andon (行灯), the bonbori (雪洞), the chōchin (提灯), and the tōrō (灯篭).

The Hindenburg light or Hindenburglicht was a source of tallow lighting used in the trenches of the First World War, named after the Commander-in-Chief of the German army in World War I, Paul von Hindenburg. It was a flat bowl approximately 5–8 cm (2–3 in) in diameter and 1–1.5 cm (0.4–0.6 in) deep, resembling the cover of Mason jar lid (Schraubglasdeckel) and made from pasteboard. This flat bowl was filled with a wax-like fat (tallow). A short wick (Docht) in the center was lit and burned for some hours. A later model of the Hindenburglicht was a "tin can (Dosenlicht) lamp." Here, a wax-filled tin can have two wicks in a holder. If both wicks are lit, a common, broad flame results.

A tealight is a candle in a thin metal or plastic cup so that the candle can liquefy completely while lit. They are typically small, circular, usually wider than their height, and inexpensive. Tealights derive their name from their use in teapot warmers, but are also used as food warmers in general, e.g. fondue.

The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, or just The Natural History of Selborne is a book by English parson-naturalist Gilbert White (1720–1793). It was first published in 1789 by his brother Benjamin. It has been continuously in print since then, with nearly 300 editions up to 2007.

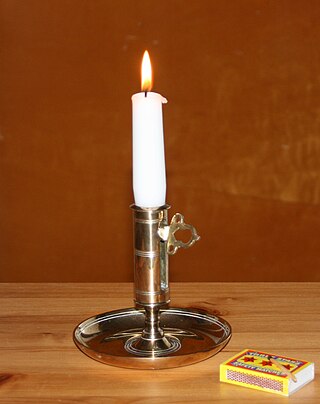

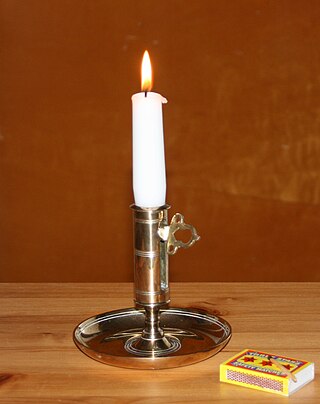

The hogscraper candlestick is an early form of lighting device commonly used in 19th-century North America and Britain, and mainly manufactured in England. The device is manufactured of tempered sheet iron, wrought in several pieces and joined by metal joinery and silver soldering. The name is derived from the candlesticks resemblance to an antique device used to scrape bristles from hog hide after slaughter. The antique lighting device commonly consists of a shaft, attached to a round base with a thumb tab ejector mechanism to remove the residual candle stub, and a round lip or "bobèche" to collect candle drippings. The "bobèche" often has a hook extension used for hanging the device.

A luchina is a long thin sliver/chip or plate of wood, most commonly used as a miniature torch for makeshift lighting of the interiors of buildings in the history of Russia. Similar implements were used in other countries, e.g., Poland, Ukraine.