Microscopy is the technical field of using microscopes to view objects and areas of objects that cannot be seen with the naked eye. There are three well-known branches of microscopy: optical, electron, and scanning probe microscopy, along with the emerging field of X-ray microscopy.

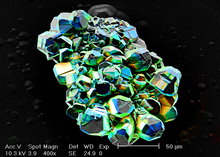

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) is a type of electron microscope that produces images of a sample by scanning the surface with a focused beam of electrons. The electrons interact with atoms in the sample, producing various signals that contain information about the surface topography and composition of the sample. The electron beam is scanned in a raster scan pattern, and the position of the beam is combined with the intensity of the detected signal to produce an image. In the most common SEM mode, secondary electrons emitted by atoms excited by the electron beam are detected using a secondary electron detector. The number of secondary electrons that can be detected, and thus the signal intensity, depends, among other things, on specimen topography. Some SEMs can achieve resolutions better than 1 nanometer.

Photoluminescence is light emission from any form of matter after the absorption of photons. It is one of many forms of luminescence and is initiated by photoexcitation, hence the prefix photo-. Following excitation, various relaxation processes typically occur in which other photons are re-radiated. Time periods between absorption and emission may vary: ranging from short femtosecond-regime for emission involving free-carrier plasma in inorganic semiconductors up to milliseconds for phosphoresence processes in molecular systems; and under special circumstances delay of emission may even span to minutes or hours.

Raman spectroscopy is a spectroscopic technique typically used to determine vibrational modes of molecules, although rotational and other low-frequency modes of systems may also be observed. Raman spectroscopy is commonly used in chemistry to provide a structural fingerprint by which molecules can be identified.

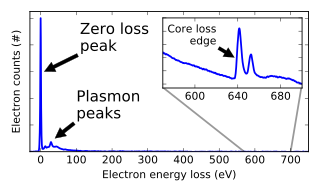

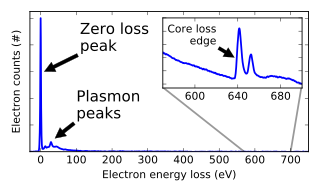

Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) is a form of electron microscopy in which a material is exposed to a beam of electrons with a known, narrow range of kinetic energies. Some of the electrons will undergo inelastic scattering, which means that they lose energy and have their paths slightly and randomly deflected. The amount of energy loss can be measured via an electron spectrometer and interpreted in terms of what caused the energy loss. Inelastic interactions include phonon excitations, inter- and intra-band transitions, plasmon excitations, inner shell ionizations, and Cherenkov radiation. The inner-shell ionizations are particularly useful for detecting the elemental components of a material. For example, one might find that a larger-than-expected number of electrons comes through the material with 285 eV less energy than they had when they entered the material. This is approximately the amount of energy needed to remove an inner-shell electron from a carbon atom, which can be taken as evidence that there is a significant amount of carbon present in the sample. With some care, and looking at a wide range of energy losses, one can determine the types of atoms, and the numbers of atoms of each type, being struck by the beam. The scattering angle can also be measured, giving information about the dispersion relation of whatever material excitation caused the inelastic scattering.

Photoemission electron microscopy is a type of electron microscopy that utilizes local variations in electron emission to generate image contrast. The excitation is usually produced by ultraviolet light, synchrotron radiation or X-ray sources. PEEM measures the coefficient indirectly by collecting the emitted secondary electrons generated in the electron cascade that follows the creation of the primary core hole in the absorption process. PEEM is a surface sensitive technique because the emitted electrons originate from a shallow layer. In physics, this technique is referred to as PEEM, which goes together naturally with low-energy electron diffraction (LEED), and low-energy electron microscopy (LEEM). In biology, it is called photoelectron microscopy (PEM), which fits with photoelectron spectroscopy (PES), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

X-ray spectroscopy is a general term for several spectroscopic techniques for characterization of materials by using x-ray radiation.

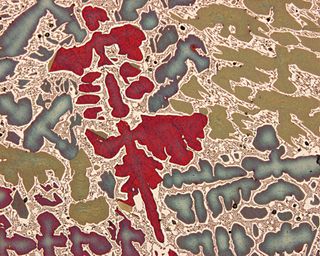

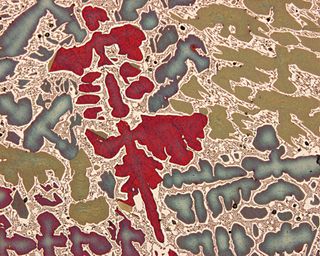

An electron microprobe (EMP), also known as an electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA) or electron micro probe analyzer (EMPA), is an analytical tool used to non-destructively determine the chemical composition of small volumes of solid materials. It works similarly to a scanning electron microscope: the sample is bombarded with an electron beam, emitting x-rays at wavelengths characteristic to the elements being analyzed. This enables the abundances of elements present within small sample volumes to be determined, when a conventional accelerating voltage of 15-20 kV is used. The concentrations of elements from lithium to plutonium may be measured at levels as low as 100 parts per million (ppm), material dependent, although with care, levels below 10 ppm are possible. The ability to quantify lithium by EPMA became a reality in 2008.

Ultrafast laser spectroscopy is a category of spectroscopic techniques using ultrashort pulse lasers for the study of dynamics on extremely short time scales. Different methods are used to examine the dynamics of charge carriers, atoms, and molecules. Many different procedures have been developed spanning different time scales and photon energy ranges; some common methods are listed below.

Characterization, when used in materials science, refers to the broad and general process by which a material's structure and properties are probed and measured. It is a fundamental process in the field of materials science, without which no scientific understanding of engineering materials could be ascertained. The scope of the term often differs; some definitions limit the term's use to techniques which study the microscopic structure and properties of materials, while others use the term to refer to any materials analysis process including macroscopic techniques such as mechanical testing, thermal analysis and density calculation. The scale of the structures observed in materials characterization ranges from angstroms, such as in the imaging of individual atoms and chemical bonds, up to centimeters, such as in the imaging of coarse grain structures in metals.

A spaser or plasmonic laser is a type of laser which aims to confine light at a subwavelength scale far below Rayleigh's diffraction limit of light, by storing some of the light energy in electron oscillations called surface plasmon polaritons. The phenomenon was first described by David J. Bergman and Mark Stockman in 2003. The word spaser is an acronym for "surface plasmon amplification by stimulated emission of radiation". The first such devices were announced in 2009 by three groups: a 44-nanometer-diameter nanoparticle with a gold core surrounded by a dyed silica gain medium created by researchers from Purdue, Norfolk State and Cornell universities, a nanowire on a silver screen by a Berkeley group, and a semiconductor layer of 90 nm surrounded by silver pumped electrically by groups at the Eindhoven University of Technology and at Arizona State University. While the Purdue-Norfolk State-Cornell team demonstrated the confined plasmonic mode, the Berkeley team and the Eindhoven-Arizona State team demonstrated lasing in the so-called plasmonic gap mode. In 2018, a team from Northwestern University demonstrated a tunable nanolaser that can preserve its high mode quality by exploiting hybrid quadrupole plasmons as an optical feedback mechanism.

The Raman microscope is a laser-based microscopic device used to perform Raman spectroscopy. The term MOLE is used to refer to the Raman-based microprobe. The technique used is named after C. V. Raman, who discovered the scattering properties in liquids.

Photoluminescence excitation is a specific type of photoluminescence and concerns the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter. It is used in spectroscopic measurements where the frequency of the excitation light is varied, and the luminescence is monitored at the typical emission frequency of the material being studied. Peaks in the PLE spectra often represent absorption lines of the material. PLE spectroscopy is a useful method to investigate the electronic level structure of materials with low absorption due to the superior signal-to-noise ratio of the method compared to absorption measurements.

Photoelectrochemical processes are processes in photoelectrochemistry; they usually involve transforming light into other forms of energy. These processes apply to photochemistry, optically pumped lasers, sensitized solar cells, luminescence, and photochromism.

The technique of vibrational analysis with scanning probe microscopy allows probing vibrational properties of materials at the submicrometer scale, and even of individual molecules. This is accomplished by integrating scanning probe microscopy (SPM) and vibrational spectroscopy. This combination allows for much higher spatial resolution than can be achieved with conventional Raman/FTIR instrumentation. The technique is also nondestructive, requires non-extensive sample preparation, and provides more contrast such as intensity contrast, polarization contrast and wavelength contrast, as well as providing specific chemical information and topography images simultaneously.

The semiconductor luminescence equations (SLEs) describe luminescence of semiconductors resulting from spontaneous recombination of electronic excitations, producing a flux of spontaneously emitted light. This description established the first step toward semiconductor quantum optics because the SLEs simultaneously includes the quantized light–matter interaction and the Coulomb-interaction coupling among electronic excitations within a semiconductor. The SLEs are one of the most accurate methods to describe light emission in semiconductors and they are suited for a systematic modeling of semiconductor emission ranging from excitonic luminescence to lasers.

The operation of a photon scanning tunneling microscope (PSTM) is analogous to the operation of an electron scanning tunneling microscope, with the primary distinction being that PSTM involves tunneling of photons instead of electrons from the sample surface to the probe tip. A beam of light is focused on a prism at an angle greater than the critical angle of the refractive medium in order to induce total internal reflection within the prism. Although the beam of light is not propagated through the surface of the refractive prism under total internal reflection, an evanescent field of light is still present at the surface.

Pump–probe microscopy is a non-linear optical imaging modality used in femtochemistry to study chemical reactions. It generates high-contrast images from endogenous non-fluorescent targets. It has numerous applications, including materials science, medicine, and art restoration.

The Paul-Drude-Institut für Festkörperelektronik German for Paul Drude Institute for Solid State Electronics (PDI) is a research institution under the auspices of the Forschungsverbund Berlin and is a member of the Leibniz Association. The institute is located at Hausvogteiplatz in Berlin-Mitte, its research activities are in basic research in the fields of physics and engineering and the areas of materials science and electronics/optoelectronics.