RNA splicing is a process in molecular biology where a newly-made precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) transcript is transformed into a mature messenger RNA (mRNA). It works by removing all the introns and splicing back together exons. For nuclear-encoded genes, splicing occurs in the nucleus either during or immediately after transcription. For those eukaryotic genes that contain introns, splicing is usually needed to create an mRNA molecule that can be translated into protein. For many eukaryotic introns, splicing occurs in a series of reactions which are catalyzed by the spliceosome, a complex of small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs). There exist self-splicing introns, that is, ribozymes that can catalyze their own excision from their parent RNA molecule. The process of transcription, splicing and translation is called gene expression, the central dogma of molecular biology.

Alternative splicing, or alternative RNA splicing, or differential splicing, is an alternative splicing process during gene expression that allows a single gene to produce different splice variants. For example, some exons of a gene may be included within or excluded from the final RNA product of the gene. This means the exons are joined in different combinations, leading to different splice variants. In the case of protein-coding genes, the proteins translated from these splice variants may contain differences in their amino acid sequence and in their biological functions.

A spliceosome is a large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex found primarily within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The spliceosome is assembled from small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) and numerous proteins. Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecules bind to specific proteins to form a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex, which in turn combines with other snRNPs to form a large ribonucleoprotein complex called a spliceosome. The spliceosome removes introns from a transcribed pre-mRNA, a type of primary transcript. This process is generally referred to as splicing. An analogy is a film editor, who selectively cuts out irrelevant or incorrect material from the initial film and sends the cleaned-up version to the director for the final cut.

A primary transcript is the single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) product synthesized by transcription of DNA, and processed to yield various mature RNA products such as mRNAs, tRNAs, and rRNAs. The primary transcripts designated to be mRNAs are modified in preparation for translation. For example, a precursor mRNA (pre-mRNA) is a type of primary transcript that becomes a messenger RNA (mRNA) after processing.

RNA-binding proteins are proteins that bind to the double or single stranded RNA in cells and participate in forming ribonucleoprotein complexes. RBPs contain various structural motifs, such as RNA recognition motif (RRM), dsRNA binding domain, zinc finger and others. They are cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins. However, since most mature RNA is exported from the nucleus relatively quickly, most RBPs in the nucleus exist as complexes of protein and pre-mRNA called heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein particles (hnRNPs). RBPs have crucial roles in various cellular processes such as: cellular function, transport and localization. They especially play a major role in post-transcriptional control of RNAs, such as: splicing, polyadenylation, mRNA stabilization, mRNA localization and translation. Eukaryotic cells express diverse RBPs with unique RNA-binding activity and protein–protein interaction. According to the Eukaryotic RBP Database (EuRBPDB), there are 2961 genes encoding RBPs in humans. During evolution, the diversity of RBPs greatly increased with the increase in the number of introns. Diversity enabled eukaryotic cells to utilize RNA exons in various arrangements, giving rise to a unique RNP (ribonucleoprotein) for each RNA. Although RBPs have a crucial role in post-transcriptional regulation in gene expression, relatively few RBPs have been studied systematically.It has now become clear that RNA–RBP interactions play important roles in many biological processes among organisms.

Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) is a class of small RNA molecules that are found within the splicing speckles and Cajal bodies of the cell nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The length of an average snRNA is approximately 150 nucleotides. They are transcribed by either RNA polymerase II or RNA polymerase III. Their primary function is in the processing of pre-messenger RNA (hnRNA) in the nucleus. They have also been shown to aid in the regulation of transcription factors or RNA polymerase II, and maintaining the telomeres.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNPs) are complexes of RNA and protein present in the cell nucleus during gene transcription and subsequent post-transcriptional modification of the newly synthesized RNA (pre-mRNA). The presence of the proteins bound to a pre-mRNA molecule serves as a signal that the pre-mRNA is not yet fully processed and therefore not ready for export to the cytoplasm. Since most mature RNA is exported from the nucleus relatively quickly, most RNA-binding protein in the nucleus exist as heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein particles. After splicing has occurred, the proteins remain bound to spliced introns and target them for degradation.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the HNRNPA1 gene. Mutations in hnRNP A1 are causative of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and the syndrome multisystem proteinopathy.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the HNRNPA2B1 gene.

snRNP70 also known as U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein 70 kDa is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SNRNP70 gene. snRNP70 is a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein that associates with U1 spliceosomal RNA, forming the U1snRNP a core component of the spliceosome. The U1-70K protein and other components of the spliceosome complex form detergent-insoluble aggregates in both sporadic and familial human cases of Alzheimer's disease. U1-70K co-localizes with Tau in neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F is a protein that in humans is encoded by the HNRNPF gene.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H is a protein that in humans is encoded by the HNRNPH1 gene.

Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 7 (SRSF7) also known as splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 7 (SFRS7) or splicing factor 9G8 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SRSF7 gene.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B, also known as HNRNPAB, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the HNRNPAB gene. Although this gene is named HNRNPAB in reference to its first cloning as an RNA binding protein with similarity to HNRNP A and HNRNP B, it is not a member of the HNRNP A/B subfamily of HNRNPs, but groups together closely with HNRNPD/AUF1 and HNRNPDL.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D-like, also known as HNRPDL, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the HNRPDL gene.

Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the PTBP1 gene.

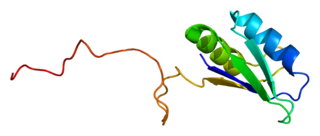

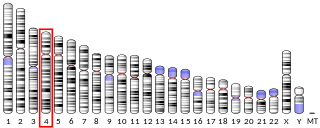

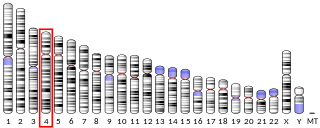

Serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1 (SRSF1) also known as alternative splicing factor 1 (ASF1), pre-mRNA-splicing factor SF2 (SF2) or ASF1/SF2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SRSF1 gene. ASF/SF2 is an essential sequence specific splicing factor involved in pre-mRNA splicing. SRSF1 is the gene that codes for ASF/SF2 and is found on chromosome 17. The resulting splicing factor is a protein of approximately 33 kDa. ASF/SF2 is necessary for all splicing reactions to occur, and influences splice site selection in a concentration-dependent manner, resulting in alternative splicing. In addition to being involved in the splicing process, ASF/SF2 also mediates post-splicing activities, such as mRNA nuclear export and translation.

An exon junction complex (EJC) is a protein complex which forms on a pre-messenger RNA strand at the junction of two exons which have been joined together during RNA splicing. The EJC has major influences on translation, surveillance, localization of the spliced mRNA, and m6A methylation. It is first deposited onto mRNA during splicing and is then transported into the cytoplasm. There it plays a major role in post-transcriptional regulation of mRNA. It is believed that exon junction complexes provide a position-specific memory of the splicing event. The EJC consists of a stable heterotetramer core, which serves as a binding platform for other factors necessary for the mRNA pathway. The core of the EJC contains the protein eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-III bound to an adenosine triphosphate (ATP) analog, as well as the additional proteins Magoh and Y14. The binding of these proteins to nuclear speckled domains has been measured recently and it may be regulated by PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathways. In order for the binding of the complex to the mRNA to occur, the eIF4AIII factor is inhibited, stopping the hydrolysis of ATP. This recognizes EJC as an ATP dependent complex. EJC also interacts with a large number of additional proteins; most notably SR proteins. These interactions are suggested to be important for mRNA compaction. The role of EJC in mRNA export is controversial.

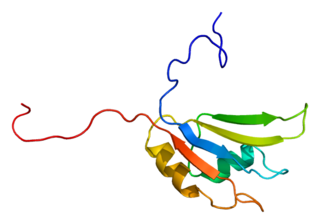

RNA recognition motif, RNP-1 is a putative RNA-binding domain of about 90 amino acids that are known to bind single-stranded RNAs. It was found in many eukaryotic proteins.

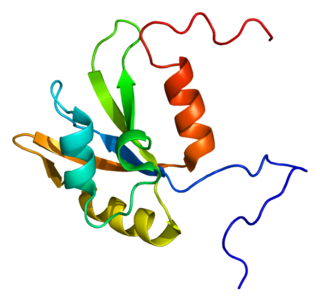

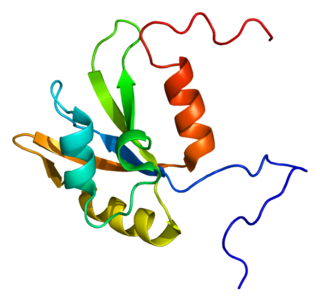

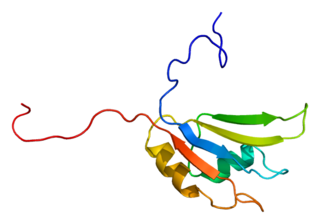

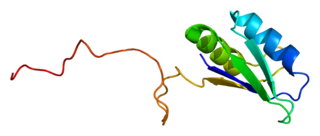

Prp8 refers to both the Prp8 protein and Prp8 gene. Prp8's name originates from its involvement in pre-mRNA processing. The Prp8 protein is a large, highly conserved, and unique protein that resides in the catalytic core of the spliceosome and has been found to have a central role in molecular rearrangements that occur there. Prp8 protein is a major central component of the catalytic core in the spliceosome, and the spliceosome is responsible for splicing of precursor mRNA that contains introns and exons. Unexpressed introns are removed by the spliceosome complex in order to create a more concise mRNA transcript. Splicing is just one of many different post-transcriptional modifications that mRNA must undergo before translation. Prp8 has also been hypothesized to be a cofactor in RNA catalysis.