Lepospondyli is a diverse taxon of early tetrapods. With the exception of one late-surviving lepospondyl from the Late Permian of Morocco, lepospondyls lived from the Early Carboniferous (Mississippian) to the Early Permian and were geographically restricted to what is now Europe and North America. Five major groups of lepospondyls are known: Adelospondyli; Aïstopoda; Lysorophia; Microsauria; and Nectridea. Lepospondyls have a diverse range of body forms and include species with newt-like, eel- or snake-like, and lizard-like forms. Various species were aquatic, semiaquatic, or terrestrial. None were large, and they are assumed to have lived in specialized ecological niches not taken by the more numerous temnospondyl amphibians that coexisted with them in the Paleozoic. Lepospondyli was named in 1888 by Karl Alfred von Zittel, who coined the name to include some tetrapods from the Paleozoic that shared some specific characteristics in the notochord and teeth. Lepospondyls have sometimes been considered to be either related or ancestral to modern amphibians or to Amniota. It has been suggested that the grouping is polyphyletic, with aïstopods being primitive stem-tetrapods, while recumbirostran microsaurs are primitive reptiles.

Adelospondyli is an order of elongated, presumably aquatic, Carboniferous amphibians. They have a robust skull roofed with solid bone, and orbits located towards the front of the skull. The limbs were almost certainly absent, although some historical sources reported them to be present. Despite the likely absence of limbs, adelospondyls retained a large part of the bony shoulder girdle. Adelospondyls have been assigned to a variety of groups in the past. They have traditionally been seen as members of the subclass Lepospondyli, related to other unusual early tetrapods such as "microsaurs", "nectrideans", and aïstopods. Analyses such as Ruta & Coates (2007) have offered an alternate classification scheme, arguing that adelospondyls were actually far removed from other lepospondyls, instead being stem-tetrapod stegocephalians closely related to the family Colosteidae.

Temnospondyli is a diverse order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carboniferous, Permian, and Triassic periods. A few species continued into the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Fossils have been found on every continent. During about 210 million years of evolutionary history, they adapted to a wide range of habitats, including freshwater, terrestrial, and even coastal marine environments. Their life history is well understood, with fossils known from the larval stage, metamorphosis, and maturity. Most temnospondyls were semiaquatic, although some were almost fully terrestrial, returning to the water only to breed. These temnospondyls were some of the first vertebrates fully adapted to life on land. Although temnospondyls are considered amphibians, many had characteristics, such as scales and armour-like bony plates, that distinguish them from modern amphibians (lissamphibians).

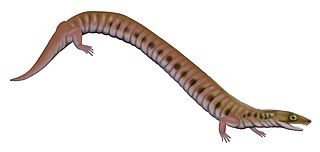

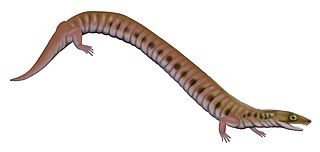

Westlothiana is a genus of reptile-like tetrapod that lived about 338 million years ago during the latest part of the Viséan age of the Carboniferous. Members of the genus bore a superficial resemblance to modern-day lizards. The genus is known from a single species, Westlothiana lizziae. The type specimen was discovered in the East Kirkton Limestone at the East Kirkton Quarry, West Lothian, Scotland in 1984. This specimen was nicknamed "Lizzie the lizard" by fossil hunter Stan Wood, and this name was quickly adopted by other paleontologists and the press. When the specimen was formally named in 1990, it was given the specific name "lizziae" in homage to this nickname. However, despite its similar body shape, Westlothiana is not considered a true lizard. Westlothiana's anatomy contained a mixture of both "labyrinthodont" and reptilian features, and was originally regarded as the oldest known reptile or amniote. However, updated studies have shown that this identification is not entirely accurate. Instead of being one of the first amniotes, Westlothiana was rather a close relative of Amniota. As a result, most paleontologists since the original description place the genus within the group Reptiliomorpha, among other amniote relatives such as diadectomorphs and seymouriamorphs. Later analyses usually place the genus as the earliest diverging member of Lepospondyli, a collection of unusual tetrapods which may be close to amniotes or lissamphibians, or potentially both at the same time.

Nectridea is the name of an extinct order of lepospondyl tetrapods from the Carboniferous and Permian periods, including animals such as Diplocaulus. In appearance, they would have resembled modern newts or aquatic salamanders, although they are not close relatives of modern amphibians. They were characterized by long, flattened tails to aid in swimming, as well as numerous features of the vertebrae.

Microsauria is an extinct, possibly polyphyletic order of amphibians from the late Carboniferous and early Permian periods. It is the most diverse and species-rich group of lepospondyls. Recently, Microsauria has been considered paraphyletic, as several other non-microsaur lepospondyl groups such as Lysorophia seem to be nested in it. Microsauria is now commonly used as a collective term for the grade of lepospondyls that were originally classified as members of Microsauria.

Neopteroplax is an extinct genus of eogyrinid embolomere closely related to European genera such as Eogyrinus and Pteroplax. Members of this genus were among the largest embolomeres in North America. Neopteroplax is primarily known from a large skull found in Ohio, although fragmentary embolomere fossils from Texas and New Mexico have also been tentatively referred to the genus. Despite its similarities to specific European embolomeres, it can be distinguished from them due to a small number of skull and jaw features, most notably a lower surangular at the upper rear portion of the lower jaw.

Acherontiscus is an extinct genus of stegocephalians that lived in the Early Carboniferous of Scotland. The type and only species is Acherontiscus caledoniae, named by paleontologist Robert Carroll in 1969. Members of this genus have an unusual combination of features which makes their placement within amphibian-grade tetrapods uncertain. They possess multi-bone vertebrae similar to those of embolomeres, but also a skull similar to lepospondyls. The only known specimen of Acherontiscus possessed an elongated body similar to that of a snake or eel. No limbs were preserved, and evidence for their presence in close relatives of Acherontiscus is dubious at best. Phylogenetic analyses created by Marcello Ruta and other paleontologists in the 2000s indicate that Acherontiscus is part of Adelospondyli, closely related to other snake-like animals such as Adelogyrinus and Dolichopareias. Adelospondyls are traditionally placed within the group Lepospondyli due to their fused vertebrae. Some analyses published since 2007 have argued that adelospondyls such as Acherontiscus may not actually be lepospondyls, instead being close relatives or members of the family Colosteidae. This would indicate that they evolved prior to the split between the tetrapod lineage that leads to reptiles (Reptiliomorpha) and the one that leads to modern amphibians (Batrachomorpha). Members of this genus were probably aquatic animals that were able to swim using snake-like movements.

Batropetes is an extinct genus of brachystelechid recumbirostran "microsaur". Batropetes lived during the Sakmarian stage of the Early Permian. Fossils attributable to the type species B. fritschi have been collected from the town of Freital in Saxony, Germany, near the city of Dresden. Additional material has been found from the Saar-Nahe Basin in southwestern Germany and has been assigned to three additional species: B. niederkirchensis, B. palatinus, and B. appelensis.

Doleserpeton is an extinct, monospecific genus of dissorophoidean temnospondyl within the family Amphibamidae that lived during the Upper Permian, 285 million years ago. Doleserpeton is represented by a single species, Doleserpeton annectens, which was first described by John R. Bolt in 1969. Fossil evidence of Doleserpeton was recovered from the Dolese Brothers Limestone Quarry in Fort Sill, Oklahoma. The genus name Doleserpeton is derived from the initial discovery site in Dolese quarry of Oklahoma and the Greek root "herp-", meaning "low or close to the ground". This transitional fossil displays primitive traits of amphibians that allowed for successful adaptation from aquatic to terrestrial environments. In many phylogenies, lissamphibians appear as the sister group of Doleserpeton.

Ostodolepis is an extinct genus of microsaur within the family Ostodolepidae. It is known from the Arroyo Formation in Texas.

Rhynchonkos is an extinct genus of microsaur. It is the only known member of the family Rhynchonkidae. Originally known as Goniorhynchus, it was renamed in 1981 because the name had already been given to another genus; the family, likewise, was originally named Goniorhynchidae but renamed in 1988. The type and only known species is R. stovalli, found from the Early Permian Fairmont Shale in Cleveland County, Oklahoma. Rhynchonkos shares many similarities with Eocaecilia, an early caecilian from the Early Jurassic of Arizona. Similarities between Rhynchonkos and Eocaecilia have been taken as evidence that caecilians are descendants of microsaurs. However, such a relationship is no longer widely accepted.

Utaherpeton is an extinct genus of lepospondyl amphibian from the Carboniferous of Utah. It is one of the oldest and possibly one of the most basal ("primitive") known lepospondyls. The genus is monotypic, including only the type species Utaherpeton franklini. Utaherpeton was named in 1991 from the Manning Canyon Shale Formation, which dates to the Mississippian-Pennsylvanian boundary. It was originally classified within Microsauria, a group of superficially lizard- and salamander-like lepospondyls that is now no longer considered to be a valid clade or evolutionary grouping, but rather an evolutionary grade consisting of the most basal lepospondyls. Utaherpeton has been proposed as both the most basal lepospondyl and the oldest "microsaur", although more derived lepospondyls are known from earlier in the Carboniferous. However, its position within Lepospondyli remains uncertain due to the incomplete preservation of the only known specimen. The inclusion of Utaherpeton in various phylogenetic analyses has resulted in multiple phylogenies that are very different from one another, making it a significant taxon in terms of understanding the interrelationships of lepospondyls.

Echinerpeton is an extinct genus of synapsid, including the single species Echinerpeton intermedium from the Late Carboniferous of Nova Scotia, Canada. The name means 'spiny lizard' (Greek). Along with its contemporary Archaeothyris, Echinerpeton is the oldest known synapsid, having lived around 308 million years ago. It is known from six small, fragmentary fossils, which were found in an outcrop of the Morien Group near the town of Florence. The most complete specimen preserves articulated vertebrae with high neural spines, indicating that Echinerpeton was a sail-backed synapsid like the better known Dimetrodon, Sphenacodon, and Edaphosaurus. However, the relationship of Echinerpeton to these other forms is unclear, and its phylogenetic placement among basal synapsids remains uncertain.

Hyloplesion is an extinct genus of microbrachomorph microsaur. It is the type and only genus within the family Hyloplesiontidae. Fossils have been found from the Czech Republic near the towns of Plzeň, Nýřany, and Třemošná, and date back to the Middle Pennsylvanian. The type species is H. longicostatum, named in 1883. Two species belonging to different genera, Seeleya pusilla and Orthocosta microscopica, have been synonymized with H. longicostatum and are thought to represent very immature individuals.

Tuditanomorpha is a suborder of microsaur lepospondyls. Tuditanomorphs lived from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian and are known from North America and Europe. Tuditanomorphs have a similar pattern of bones in the skull roof. Tuditanomorphs display considerable variability, especially in body size, proportions, dentition, and presacral vertebral count. Currently there are seven families of tuditanomorphs, with two being monotypic. Tuditanids, gymnarthrids, and pantylids first appear in the Lower Pennsylvanian. Goniorhynchidae, Hapsidopareiontidae, Ostodolepidae, and Trihecatontidae appear in the Late Pennsylvanian and Early Permian.

Ostodolepidae, also spelled Ostodolepididae, is an extinct family of Early Permian microsaurs. They are unique among microsaurs in that they were large, reaching lengths of up to 2 feet (61 cm), terrestrial, and presumably fossorial. Ostodolepid remains have been found from Early Permian beds in Texas, Oklahoma, and Germany.

Tuditanidae is an extinct family of tuditanomorph microsaurs. Fossils have been found from Nova Scotia, Ohio, and the Czech Republic and are Late Carboniferous in age.

Antlerpeton is an extinct genus of early tetrapod from the Early Carboniferous of Nevada. It is known from a single poorly preserved skeleton from the Diamond Peak Formation of Eureka County. A mix of features in its compound vertebrae suggest that Antlerpeton is a primitive stem tetrapod that has affinities with later, more advanced forms. Its robust pelvis and hind limbs allowed for effective locomotion on land, but the animal was likely still tied to a semiaquatic lifestyle near the coast.

Altenglanerpeton is an extinct genus of microsaur amphibian from the Late Carboniferous or Early Permian of Germany. Altenglanerpeton was named in 2012 after the Altenglan Formation in which it was found. The type and only species is A. schroederi.