Related Research Articles

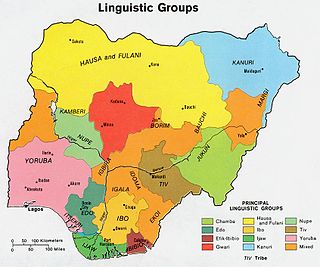

Biafra, officially the Republic of Biafra, was a partially recognised state in West Africa that declared independence from Nigeria and existed from 1967 until 1970. Its territory consisted of the former Eastern Region of Nigeria, predominantly inhabited by the Igbo ethnic group. Biafra was established on 30 May 1967 by Igbo military officer and Eastern Region governor Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu under his presidency, following a series of ethnic tensions and military coups after Nigerian independence in 1960 that culminated in the 1966 anti-Igbo pogrom. The Nigerian military proceeded in an attempt to reclaim the territory of Biafra, resulting in the start of the Nigerian Civil War. Biafra was officially recognised by Gabon, Haiti, Ivory Coast, Tanzania, and Zambia while receiving de facto recognition and covert military support from France, Portugal, Israel, South Africa and Rhodesia. After nearly three years of war, during which around two million Biafran civilians died, president Ojukwu fled into exile in Ivory Coast as the Nigerian military approached the capital of Biafra. Philip Effiong became the second president of Biafra, and he oversaw the surrender of Biafran forces to Nigeria.

Chukwuemeka "Emeka" Odumegwu Ojukwu was a Nigerian military officer and politician who served as President of the Republic of Biafra from 1967 to 1970 during the Nigerian Civil War. He previously served as military governor of the Eastern Region of Nigeria, which he declared as the independent state of Biafra.

Yakubu Dan-Yumma "Jack" Gowon is a Nigerian former Head of State and statesman who led the Federal military government war efforts during the Nigerian Civil War.

The Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Biafran War, was a civil war fought between Nigeria and the Republic of Biafra, a secessionist state which had declared its independence from Nigeria in 1967. Nigeria was led by General Yakubu Gowon, and Biafra by Lieutenant Colonel Chukwuemeka "Emeka" Odumegwu Ojukwu. Biafra represented the nationalist aspirations of the Igbo ethnic group, whose leadership felt they could no longer coexist with the federal government dominated by the interests of the Muslim Hausa-Fulanis of Northern Nigeria. The conflict resulted from political, ethnic, cultural and religious tensions which preceded the United Kingdom's formal decolonisation of Nigeria from 1960 to 1963. Immediate causes of the war in 1966 included a military coup, a counter-coup, and anti-Igbo pogroms in Northern Nigeria.

Johnson Thomas Umunnakwe Aguiyi-Ironsi was a Nigerian general who was the first military head of state of Nigeria. He was appointed to head the country after the 15 January 1966 military coup.

Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick Chukwuma "Kaduna" Nzeogwu was a Nigerian military officer who played a leading role in the 1966 Nigerian coup d'état, which overthrew the First Nigerian Republic.

The First Republic was the republican government of Nigeria between 1963 and 1966 governed by the first republican constitution. The country's government was based on a federal form of the Westminster system. The period between 1 October 1960, when the country gained its independence and 15 January 1966, when the first military coup d’état took place, is also generally referred to as the First Republic. The first Republic of Nigeria was ruled by different leaders representing their regions as premiers in a federation during this period.

A Sabon Gari is a section of cities and towns in Northern Nigeria, South Central Niger and Northern Cameroon whose residents are not indigenous to Hausa lands.

Hassan Usman Katsina, titled Chiroman Katsina, was a Nigerian general who was the last Governor of Northern Nigeria. He served as Chief of Army Staff during the Nigerian Civil War and later became the Deputy Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters.

Anti-Igbo sentiment encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings towards the Igbo people. The Igbo people make up a majority of the population in South East, Nigeria and part of the populations of the South South and the Middle Belt zones. Igbophobia can be observed in critical and hostile behaviour such as political and religious discrimination as well as violence towards Igbo people.

Events in the year 1966 in Nigeria.

The 1966 Nigerian Counter-coup was the second of many military coups in Nigeria. It was masterminded by Lt. Colonel Murtala Muhammed and many other northern military officers. The coup began as a mutiny at roughly midnight of 28 July 1966 and was a reaction to the killings of Northern politicians and officers by some soldiers on 15 January 1966. The coup resulted in the murder of Nigeria's first military Head of State General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi and Lt Colonel Adekunle Fajuyi in Ibadan by disgruntled northern non-commissioned officers (NCOs). Upon the termination of Ironsi's government, Lt. Colonel Yakubu Gowon was appointed Head of State by the coup conspirators.

Federalism in Nigeria refers to the devolution of self-governance by the West African nation of Nigeria to its federated states, who share sovereignty with the Federal Government.

Joseph Akahan born Joseph Akaahan Agbo, was a Nigerian military officer and Chief of Army Staff (Nigeria) from May 1967 until May 1968, when he was killed in a helicopter crash during the Nigerian Civil War.

William Walbe, was a colonel in the Nigerian Army who served as the military aide-de-camp (ADC) to General Yakubu Gowon, the third Nigerian Head of State.

The Operation UNICORD was an offensive launched by the Nigerian Army at the beginning of the Nigerian Civil War. It involved the capture of 6 major Biafran towns near their northern border.

Victor Adebukunola Banjo was a colonel in the Nigerian Army. He fought in the Biafran Army during the Nigerian Civil War. Banjo was accused of being a coup plotter against Nigerian Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa by the government of Aguyi Ironsi. He was alleged to have staged a coup plot against Biafran President Odumegwu Ojukwu and was executed as a result. Ojukwu's first military judge stated that was not enough evidence to convict him of coup charges, but he was found guilty by a second military tribunal.

On 15 January 1966, rebellious soldiers carrying out a military putsch led by Kaduna Nzeogwu and 4 others, killed 22 people including the prime minister of Nigeria, many senior politicians, senior Army officers and their wives, and sentinels on protective duty. The coup plotters attacked the cities of Kaduna, Ibadan, and Lagos while also blockading the Niger and Benue River within a two-day timespan, before being overcome by loyal forces.

Ogbugo Kalu was a Nigerian military officer who served in the Nigerian Army and later the Biafran Army during the Nigerian Civil War. Kalu was also commander of the Nigerian Military Training College (NMTC) in Kaduna following the 1966 Nigerian coup d'état.

Igbo nationalism is a range of ethnic nationalist ideologies relating to the Igbo people of southeastern Nigeria. While the term is defined as seeking Igbo self-determination by some, others argue that it refers to the preservation and revival of Igbo culture and, for others, the development of Igboland stemming from the philosophy, Aku luo uno, which means "wealth builds the home".

References

- ↑ "Civil War". countrystudies.us. Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. 1991. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

The estimated number of deaths ranged as high as 30,000, although the figure was probably closer to 8,000 to 10,000.

- ↑ Last, Murray (October 2005). "Poison and Medicine: Ethnicity, Power and Violence in a Nigerian City, 1966–1986 by Douglas A. Anthony Review by: Murray Last". The Royal African Society. 104 (417): 710–711. JSTOR 3518821.

- ↑ "Civil War". countrystudies.us. Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. 1991. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

The estimated number of deaths ranged as high as 30,000. More than 1 million Igbo returned to the Eastern Region. In retaliation, some northerners were massacred in Port Harcourt and other eastern cities, and a counterexodus of non-Igbo was under way.

- ↑ Van Den Bersselaar, Dmitri (3 March 2011). "Douglas A. Anthony Poison and Medicine: ethnicity, power, and violence in a Nigerian city, 1966 to 1986. Oxford: James Currey". Africa. 74 (4): 711–713. doi:10.2307/3556867. JSTOR 3556867. ISBN 0852559593 , 0852559542 , 0325070520 , 0325070512)

- 1 2 3 4 Post, K. W. J. (January 1968). "Is There a Case for Biafra?". International Affairs. 44 (1): 26–39. doi:10.2307/2613526. JSTOR 2613526.

- ↑ Gamji.com "Operation Aure".

- 1 2 Nixon, Charles (July 1972). "Self-Determination: The Nigeria/Biafra Case". World Politics. 24 (4): 473–497. doi:10.2307/2010453. JSTOR 2010453. S2CID 155019740.

- ↑ Vickers, Michael (1970). "Competition and Control in Modern Nigeria: Origins of the War with Biafra". International Journal. 25 (3): 630. doi:10.1177/002070207002500310. JSTOR 40200860. S2CID 147149826.

- 1 2 Keil, Charles (January 1970). "The Price of Nigerian Victory". Africa Today. 17 (1): 1–3. JSTOR 4185054.

- ↑ Olorunyomi, Ladi (November 22, 2021). "INTERVIEW: Why every Nigerian should be proud of the Sokoto Caliphate — Prof Murray Last". www.premiumtimesng.com. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- ↑ Nnoli, Okwudiba. "Ethnic Violence in Nigeria: A Historical Perspective" (PDF). Indiana.edu. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ Ojo, Bamidele A. (2001). Problems and Prospects of Sustaining Democracy in Nigeria. Nova Science. ISBN 978-1-56072-949-5.

- ↑ Omaka, Arua (17 February 2014). "The Forgotten Victims: Ethnic Minorities in The Nigeria-Biafra War, 1967-1970". Journal of Retracing Africa (JORA). 1 (1): 25–40. ISSN 2168-0531 . Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- 1 2 3 Akinyemi, A.B. (October 1972). "The British Press and the Nigerian Civil War". African Affairs. 71 (285): 408–426. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a096282. JSTOR 720847.

- ↑ Nafziger, Wayne (July 1972). "The Economic Impact of the Nigerian Civil War". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 10 (2): 223–245. doi:10.1017/s0022278x00022369. JSTOR 159964. S2CID 154808210.

- 1 2 McKenna, Joseph C. (1969). "Elements of a Nigerian Peace". Foreign Affairs. 47 (4): 668–680. doi:10.2307/20039407. JSTOR 20039407.

- ↑ Abbott, Charles; Anthony, Douglas A. (2003). "Poison and Medicine: Ethnicity, Power, and Violence in a Nigerian City, 1966–86". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 36 (1): 133–136. doi:10.2307/3559324. JSTOR 3559324.