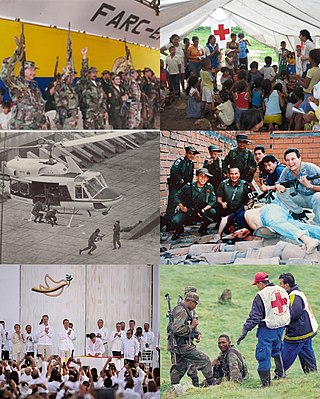

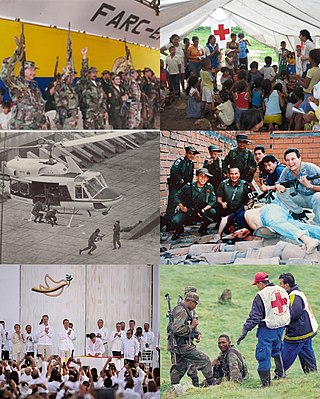

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People's Army is a Marxist–Leninist guerrilla group involved in the continuing Colombian conflict starting in 1964. The FARC-EP was officially founded in 1966 from peasant self-defense groups formed from 1948 during La Violencia as a peasant force promoting a political line of agrarianism and anti-imperialism. They are known to employ a variety of military tactics, in addition to more unconventional methods, including terrorism.

Álvaro Uribe Vélez is a Colombian who served as the 31st President of Colombia from 7 August 2002 to 7 August 2010.

Andrés Pastrana Arango is a Colombian politician who was the 30th President of Colombia from 1998 to 2002, following in the footsteps of his father, Misael Pastrana Borrero, who was president from 1970 to 1974.

The Colombian Conservative Party is a conservative political party in Colombia. The party was formally established in 1849 by Mariano Ospina Rodríguez and José Eusebio Caro.

The Colombian conflict began on May 27, 1964, and is a low-intensity asymmetric war between the government of Colombia, far-right paramilitary groups and crime syndicates, and far-left guerrilla groups, fighting each other to increase their influence in Colombian territory. Some of the most important international contributors to the Colombian conflict include multinational corporations, the United States, Cuba, and the drug trafficking industry.

Luciano Marín Arango, better known as Iván Márquez, is a Colombian guerrilla leader, member of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), part of its secretariat higher command and advisor to the Northwestern and Caribbean blocs. He was part of the FARC negotiators that concluded a peace agreement with President Juan Manuel Santos. On 29 August 2019, Márquez abandoned the peace process and announced a renewed armed conflict with the Colombian government.

Juan Manuel Santos Calderón is a Colombian politician who was the President of Colombia from 2010 to 2018. He was the sole recipient of the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize.

Humberto de la Calle Lombana is a Colombian lawyer and politician. He served as Vice President of Colombia from 1994 to 1997. De La Calle served in the cabinet as Interior Minister under two Presidents, Andrés Pastrana and César Gaviria. He also served as Ambassador to Spain and the United Kingdom. After 2003, De La Calle worked at his own Law firm which specialises in advising and representing international clients in Colombia. In October 2012 he was appointed by President Juan Manuel Santos as the chief negotiator in the peace process with the FARC.

Piedad Esneda Córdoba Ruiz was a Colombian lawyer and politician who served as a senator from 1994 to 2010. A Liberal Party politician, she also served as a member of the Chamber of Representatives of Colombia for Antioquia from 1992 to 1994.

The 2008 Andean diplomatic crisis was a diplomatic stand-off involving the South American countries of Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela. It began with an incursion into Ecuadorian territory across the Putumayo River by the Colombian military on March 1, 2008, leading to the deaths of over twenty militants, including Raúl Reyes and sixteen other members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). This incursion led to increased tension between Colombia and Ecuador and the movement of Venezuelan and Ecuadorian troops to their borders with Colombia.

Presidential elections were held in Colombia on 25 May 2014. Since no candidate received 50% of the vote in the first round, a run-off between the two candidates with the most votes took place three weeks later on 15 June 2014. According to the official figures released by the National Registry office, as of 22 May 2014 32,975,158 Colombians were registered and entitled to vote in the 2014 presidential election, including 545,976 Colombians resident abroad. Incumbent president Juan Manuel Santos was allowed to run for a second consecutive term. In the first round, Santos and Óscar Iván Zuluaga of the Democratic Center were the two highest-polling candidates and were the contestants in the 15 June run-off. In the second round, Santos was re-elected president, gaining 51% of the vote compared with 45% for Zuluaga.

Presidential elections were held in Colombia on 27 May 2018. As no candidate received a majority of the vote, the second round of voting was held on 17 June. Incumbent president Juan Manuel Santos was ineligible to seek a third term. Iván Duque, a senator, defeated Gustavo Petro, former mayor of Bogotá, in the second round. Duque's victory made him one of the youngest individuals elected to the presidency, aged 42. His running mate, Marta Lucía Ramírez, was the first woman elected to the vice presidency in Colombian history.

The Colombian peace process is the peace process between the Colombian government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC–EP) to bring an end to the Colombian conflict, which eventually led to the Peace Agreements between the Colombian Government of Juan Manuel Santos and FARC-EP. Negotiations began in September 2012, and mainly took place in Havana, Cuba. Negotiators announced a final agreement to end the conflict and build a lasting peace on August 24, 2016. However, a referendum to ratify the deal on October 2, 2016 was unsuccessful after 50.2% of voters voted against the agreement with 49.8% voting in favor. Afterward, the Colombian government and the FARC signed a revised peace deal on November 24 and sent it to Congress for ratification instead of conducting a second referendum. Both houses of Congress ratified the revised peace agreement on November 29–30, 2016, thus marking an end to the conflict.

The Commons, previously Common Alternative Revolutionary Force until 24 January 2021, is a communist political party in Colombia, established in 2017 as the political successor of the former rebel group the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The peace accords agreed upon by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia and the Colombian government in 2016 provided for the FARC's participation in politics as a legal, registered political party following its successful disarmament.

Claudia Nayibe López Hernández is a Colombian politician. She was a Senator of the Republic of Colombia and was the vice-presidential candidate in the 2018 presidential election for the Green Alliance party. In October 2019, she was elected mayor of Bogotá, the first woman and as well the first openly LGBT person to be elected to this position.

The 2021 Apure clashes started on 21 March 2021 in the south of the Páez Municipality, in the Apure state in Venezuela, specifically in La Victoria, a location bordering with Colombia, between guerrilla groups identified as Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP) dissidents and the Venezuelan government led by Nicolás Maduro.

Álvaro Leyva Durán is a Colombian lawyer, economist, politician, human rights defender and diplomat. He has been the Minister of Foreign Affairs for Colombia in the government of Gustavo Petro since 7 August 2022. On 7 February 2024, he was suspended from his ministerial position for three months over an investigation into potential violations of procurement laws.

Imelda Daza Cotes is a Colombian-Swedish economist, teacher, and politician.

Álvaro Uribe's term as the 31st president of Colombia began with his first inauguration on August 7, 2002 and ended on August 7, 2010. Uribe, candidate of the Colombia First party of Antioquia, took office after a decisive victory about the Liberal candidate Horacio Serpa in the 2002 presidential election. Four years later, in the 2006 presidential election, he defeated the Democratic Pole candidate, Carlos Gaviria, to win re-election.

Juan Manuel Santos's term as the 32nd president of Colombia began with his first inauguration on August 7, 2010, and ended on August 7, 2018. Santos, a center-right leader from Bogotá, took office after a landslide victory over the leftist leader. Antanas Mockus in the 2010 presidential election. Four years later, in the 2014 presidential election, he narrowly defeated the Democratic Center candidate Óscar Iván Zuluaga to win re-election. Santos was succeeded by right-wing leader Iván Duque, who won the 2018 presidential election.