Comet Hale–Bopp is a long-period comet that was one of the most widely observed of the 20th century and one of the brightest seen for many decades.

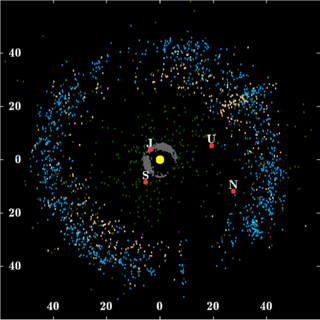

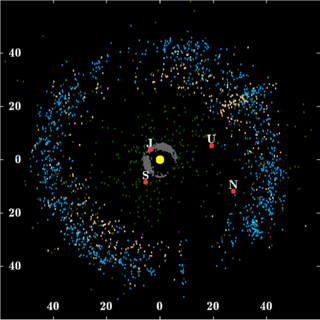

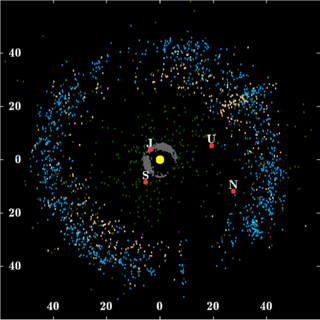

The Kuiper belt is a circumstellar disc in the outer Solar System, extending from the orbit of Neptune at 30 astronomical units (AU) to approximately 50 AU from the Sun. It is similar to the asteroid belt, but is far larger—20 times as wide and 20–200 times as massive. Like the asteroid belt, it consists mainly of small bodies or remnants from when the Solar System formed. While many asteroids are composed primarily of rock and metal, most Kuiper belt objects are composed largely of frozen volatiles, such as methane, ammonia, and water. The Kuiper belt is home to most of the objects that astronomers generally accept as dwarf planets: Orcus, Pluto, Haumea, Quaoar, and Makemake. Some of the Solar System's moons, such as Neptune's Triton and Saturn's Phoebe, may have originated in the region.

2060 Chiron is a ringed small Solar System body in the outer Solar System, orbiting the Sun between Saturn and Uranus. Discovered in 1977 by Charles Kowal, it was the first-identified member of a new class of objects now known as centaurs—bodies orbiting between the asteroid belt and the Kuiper belt. Chiron is named after the centaur Chiron in Greek mythology.

In planetary astronomy, a centaur is a small Solar System body that orbits the Sun between Jupiter and Neptune and crosses the orbits of one or more of the giant planets. Centaurs generally have unstable orbits because of this; almost all their orbits have dynamic lifetimes of only a few million years, but there is one known centaur, 514107 Kaʻepaokaʻawela, which may be in a stable orbit. Centaurs typically exhibit the characteristics of both asteroids and comets. They are named after the mythological centaurs that were a mixture of horse and human. Observational bias toward large objects makes determination of the total centaur population difficult. Estimates for the number of centaurs in the Solar System more than 1 km in diameter range from as low as 44,000 to more than 10,000,000.

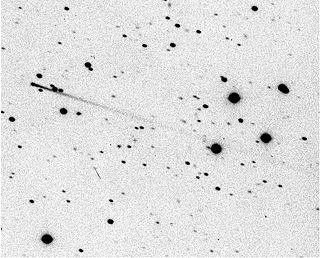

Comet Elst–Pizarro is a body that displays characteristics of both asteroids and comets, and is the prototype of active asteroids. Its orbit keeps it within the asteroid belt, yet it displayed a dust tail like a comet while near perihelion in 1996, 2001, and 2007.

3200 Phaethon, provisionally designated 1983 TB, is an active Apollo asteroid with an orbit that brings it closer to the Sun than any other named asteroid. For this reason, it was named after the Greek myth of Phaëthon, son of the sun god Helios. It is 5.8 km (3.6 mi) in diameter and is the parent body of the Geminids meteor shower of mid-December. With an observation arc of 35+ years, it has a very well determined orbit. The 2017 Earth approach distance of about 10 million km was known with an accuracy of ±700 m.

596 Scheila is a main-belt asteroid and main-belt comet orbiting the Sun. It was discovered on 21 February 1906 by August Kopff from Heidelberg. Kopff named the asteroid after a female English student with whom he was acquainted.

Active asteroids are small Solar System bodies that have asteroid-like orbits but show comet-like visual characteristics. That is, they show a coma, tail, or other visual evidence of mass-loss, but their orbits remain within Jupiter's orbit. These bodies were originally designated main-belt comets (MBCs) in 2006 by astronomers David Jewitt and Henry Hsieh, but this name implies they are necessarily icy in composition like a comet and that they only exist within the main-belt, whereas the growing population of active asteroids shows that this is not always the case.

118401 LINEAR (provisional designation 1999 RE70, comet designation 176P/LINEAR) is an active asteroid and main-belt comet that was discovered by the Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR) 1-metre telescopes in Socorro, New Mexico on September 7, 1999. (118401) LINEAR was discovered to be cometary on November 26, 2005, by Henry H. Hsieh and David C. Jewitt as part of the Hawaii Trails project using the Gemini North 8-m telescope on Mauna Kea and was confirmed by the University of Hawaii's 2.2-m (88-in) telescope on December 24–27, 2005, and Gemini on December 29, 2005. Observations using the Spitzer Space Telescope have resulted in an estimate of 4.0±0.4 km for the diameter of (118401) LINEAR.

An extinct comet is a comet that has expelled most of its volatile ice and has little left to form a tail and coma. In a dormant comet, rather than being depleted, any remaining volatile components have been sealed beneath an inactive surface layer.

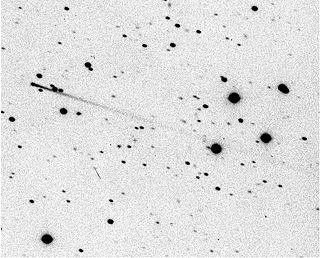

354P/LINEAR, provisionally designated P/2010 A2 (LINEAR), is a small main-belt asteroid that was impacted by another asteroid sometime before 2010. It was discovered by the Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR) at Socorro, New Mexico on 6 January 2010. The asteroid possesses a dusty, X-shaped, comet-like debris trail that has remained nearly a decade since impact. This was the first time a small-body collision had been observed; since then, minor planet 596 Scheila has also been seen to undergo a collision, in late 2010. The tail is created by millimeter-sized particles being pushed back by solar radiation pressure.

The five-planet Nice model is a numerical model of the early Solar System that is a revised variation of the Nice model. It begins with five giant planets, the four that exist today plus an additional ice giant between Saturn and Uranus in a chain of mean-motion resonances.

The jumping-Jupiter scenario specifies an evolution of giant-planet migration described by the Nice model, in which an ice giant is scattered inward by Saturn and outward by Jupiter, causing their semi-major axes to jump, and thereby quickly separating their orbits. The jumping-Jupiter scenario was proposed by Ramon Brasser, Alessandro Morbidelli, Rodney Gomes, Kleomenis Tsiganis, and Harold Levison after their studies revealed that the smooth divergent migration of Jupiter and Saturn resulted in an inner Solar System significantly different from the current Solar System. During this migration secular resonances swept through the inner Solar System exciting the orbits of the terrestrial planets and the asteroids, leaving the planets' orbits too eccentric, and the asteroid belt with too many high-inclination objects. The jumps in the semi-major axes of Jupiter and Saturn described in the jumping-Jupiter scenario can allow these resonances to quickly cross the inner Solar System without altering orbits excessively, although the terrestrial planets remain sensitive to its passage.

(82158) 2001 FP185 (provisional designation 2001 FP185) is a highly eccentric trans-Neptunian object from the scattered disc in the outermost part of the Solar System, approximately 330 kilometers in diameter. It was discovered on 26 March 2001, by American astronomer Marc Buie at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, United States.

In planetary science a streaming instability is a hypothetical mechanism for the formation of planetesimals in which the drag felt by solid particles orbiting in a gas disk leads to their spontaneous concentration into clumps which can gravitationally collapse. Small initial clumps increase the orbital velocity of the gas, slowing radial drift locally, leading to their growth as they are joined by faster drifting isolated particles. Massive filaments form that reach densities sufficient for the gravitational collapse into planetesimals the size of large asteroids, bypassing a number of barriers to the traditional formation mechanisms. The formation of streaming instabilities requires solids that are moderately coupled to the gas and a local solid to gas ratio of one or greater. The growth of solids large enough to become moderately coupled to the gas is more likely outside the ice line and in regions with limited turbulence. An initial concentration of solids with respect to the gas is necessary to suppress turbulence sufficiently to allow the solid to gas ratio to reach greater than one at the mid-plane. A wide variety of mechanisms to selectively remove gas or to concentrate solids have been proposed. In the inner Solar System the formation of streaming instabilities requires a greater initial concentration of solids or the growth of solid beyond the size of chondrules.

2I/Borisov, originally designated C/2019 Q4 (Borisov), is the first observed rogue comet and the second observed interstellar interloper after ʻOumuamua. It was discovered by the Crimean amateur astronomer and telescope maker Gennadiy Borisov on 29 August 2019 UTC.

Chimera is a NASA mission concept to orbit and explore 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1 (SW1), an active, outbursting small icy body in the outer Solar System. The concept was developed in response to the 2019 NASA call for potential missions in the Discovery-class, and it would have been the first spacecraft encounter with a Centaur and the first orbital exploration of a small body in the outer Solar System. The Chimera proposal was ranked in the first tier of submissions, but was not selected for further development for the programmatic reason of maintaining scientific balance.

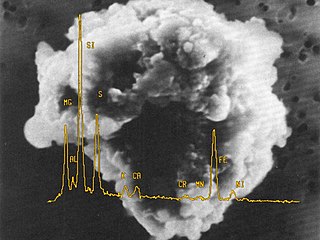

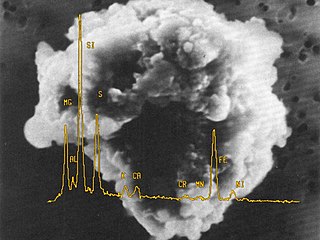

Dust astronomy is a subfield of astronomy that uses the information contained in individual cosmic dust particles ranging from their dynamical state to its isotopic, elemental, molecular, and mineralogical composition in order to obtain information on the astronomical objects occurring in outer space. Dust astronomy overlaps with the fields of Planetary science, Cosmochemistry, and Astrobiology.

P/2013 R3 (Catalina–PanSTARRS) was an active main-belt asteroid that disintegrated from 2013 to 2014 due to the centrifugal breakup of its rapidly-rotating nucleus. It was discovered by astronomers of the Catalina and Pan-STARRS sky surveys on 15 September 2013. The disintegration of this asteroid ejected numerous fragments and dusty debris into space, which temporarily gave it a diffuse, comet-like appearance with a dust tail blown back by solar radiation pressure. Observations by ground-based telescopes in October 2013 revealed that P/2013 R3 had broken up into four major components, with later Hubble Space Telescope observations showing that these components have further broken up into at least thirteen smaller fragments ranging 100–400 meters (330–1,310 ft) in diameter. P/2013 R3 was never seen again after February 2014.

483P/PanSTARRS is a pair of active main-belt asteroids that split apart from each other in early 2010. The brightest and largest component of the pair, P/2016 J1-A, was discovered first by the Pan-STARRS 1 survey at Haleakalā Observatory on 5 May 2016. Follow-up observations by the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope at Mauna Kea Observatory discovered the second component, P/2016 J1-B, on 6 May 2016. Both asteroids are smaller than 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) in diameter, with P/2016 J1-A being roughly 0.6 km (0.37 mi) in diameter and P/2016 J1-B being roughly 0.3 km (0.19 mi) in diameter. The two components recurrently exhibit cometary activity as they approach the Sun near perihelion, suggesting that their activity is driven by sublimation of volatile compounds such as water.